Though self-reliance in energy generation is not one of the five pillars of Atmanirbhar Bharat, energy is essential to power it. The mission finds synergy with the government's lofty commitment made five years ago in Paris of bringing new and renewable energy to 40 per cent of the total energy mix in the country by 2030. Given that India is a developing economy with an increasing demand for electricity, it cannot eliminate fossil fuel from the energy equation. While long gestation periods slow down nuclear projects, the new and renewable energy commitment will at least keep the country's carbon footprint from expanding.

The renewable energy sector comprises solar, wind, tidal and biomass. Though wind is the largest source of clean energy, comprising 10 per cent (37.68GW) of the total energy generation of India, solar is now the flagship. At the Paris summit, Prime Minister Narendra Modi floated the idea of an International Solar Alliance, which is now the first multilateral organisation to be headquartered in India. The country has also given itself the target of generating 100GW of solar energy by 2022. With 37GW capacity installed and another 25GW under construction, India could reach the target by the deadline, despite the pandemic and economic slowdown.

The issue, however, is about how self-reliant and “clean” this solar energy generation really is. Solar energy is generated from a composite unit called a module, which itself is made of a number of cells. These cells are composed of wafers, made of polysilicon. The focus has been on ramping up the capacity to manufacture cells and modules, the raw material for which is importedÅlargely from China. In 2019, India imported cells, panels and wafers worth $1.5 billion, of which material worth $1.2 billion was from China, says Sanghamitra B. Jayant, senior manager, corporate strategic management wing of Bharat Heavy Electronics Limited (BHEL).

Industry experts feel that the government needs to step in here, and provide variable gap funding (VGF) to boost domestic production of solar plant parts. Their production itself is energy-intensive and requires big investment in R&D. China, with its economies of scale, is able to produce them at costs that Indian manufacturers simply cannot match under present conditions.

Also read

- No 'Atmanirbharta' this, few takers for India’s rifles, pistols

- Indian Navy keeping strong vigil of Chinese vessel movements: Admiral Hari Kumar

- Mahatma Gandhi's ideas have answers to today's challenges, says PM Modi

- Vehicle scrappage policy to help attain Atmanirbhar Bharat: PM Modi

- Aero India to kick off with LCA Tejas deal

- UP steps up economic revival measures for MSMEs

The government certainly has given the boost to solar energy production, with several government enterprises mandating the use of clean energy. Indian Railways, for instance, plans to procure 3GW of solar-generated electricity, and domestic content requirement (DCR) is an important prerequisite. But without giving sufficient boost, the domestic manufacturing remains largely at the assembling stages. The initial parts are still imported.

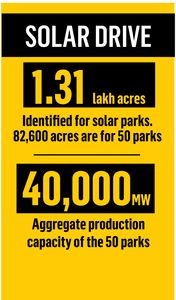

The other challenge with solar power is that it requires vast acreage, much higher than thermal generation. According to the ministry of new and renewable energy (MNRE), 1.31 lakh acres has been identified for solar parks, of which 82,600 acres have been acquired for developing 50 parks with an aggregate capacity of 40,000MW. However, the government has not focussed as much on rooftop solar generation. As Jayant says, the future has to be rooftop panels, given the limitations of space. Yet, rooftop generation has only reached around 10 per cent of its 40,000MW target for 2022. Elsewhere in the world, rooftop generation is the mainstay of solar production.

Chetan Singh Solanki, IIT Bombay professor and founder of Energy Swaraj Foundation for popularising solar energy generation at domestic levels, notes that small plants are not a priority with the government, given its big target. “It is easier to sanction a 500MW project than to encourage five lakh homes with rooftop panels of 1KW,” he said. “Also, the government's claim of having already provided electricity to each home comes in the way of promoting domestic production.”

Rooftop generation depends largely on the system of net metering, where the individual gives the power to the grid and adjusts it with the monthly power bill. “In India, the discoms (distribution companies) are still not too savvy with the system. The bureaucratic hassle is huge and therefore is a disincentive,” said Solanki. “Worse is the trend of providing free electricity, forget subsidised (power). No competition can withstand a freebie.”

India is a newcomer to solar energy generation, with the National Solar Mission coming out only in 2010. Wind energy is a more mature project here, with a presence of over two decades. Yet, according to ministry figures, the growth in wind generation is stagnating—it grew by only 2.07GW last year. Unlike solar, the wind energy sector already has a good Make in India tradition, with leading producers Tamil Nadu and Gujarat already having international players like Denmark-based Vestas manufacturing components, largely towers and plates, in these states.

Wind power generation, too, could do with some more attention. According to the National Institute of Wind Energy, India has an offshore wind energy generation potential of 70GW, as well as an installable capacity of 695GW on land, of which 347GW can be done on cultivable lands.

A little more attention to solar component production and a boost to the wind sector can go a long way in making India's renewable energy production more atmanirbhar.