In a webinar organised by the Federation of Indian Chambers of Commerce and Industry on August 27, Prime Minister Narendra Modi spelt out how the government wanted to make India’s defence industry self-reliant. “Our resolve for Atmanirbhar Bharat is not inward-looking,” he said. “It is to make India capable and to boost global peace and economy.”

India has the third largest annual defence budget ($70 billion in 2020), behind USA ($732 billion) and China ($261 billion). It imports 9.2 per cent of global arms, second only to Saudi Arabia. As much as 30 per cent of India’s defence budget is spent on capital acquisitions—90 per cent of them are imports.

In May, Union Finance Minister Nirmala Sitharaman, who held the defence portfolio earlier, raised the automatic-route limit for FDI in the sector to 74 per cent from 49 per cent, allowing foreign players to own a controlling stake in joint ventures with Indian companies. Several other measures were announced to boost domestic production.

Under the ‘Make in India’ initiative, the government had been trying to increase domestic defence manufacturing and create jobs. The renewed impetus under Atmanirbhar Bharat is aimed at reducing dependence on imported military hardware. To give priority to indigenous items, necessary changes have been made in the defence procurement policy, the guiding document for military procurement.

The government’s thrust is evident from the two proposed defence industrial corridors—in Tamil Nadu and Uttar Pradesh—and the launch of the Innovations for Defence Excellence, an initiative to boost technology development. A defence planning committee headed by National Security Adviser Ajit Doval, with the three service chiefs and the secretaries of defence and expenditure as members, was constituted to speed up modernisation of the armed forces.

The defence ministry has bifurcated the procurement budget into two: domestic purchases and foreign procurements. An import embargo has been laid on as many as 101 items—including artillery guns, light military transport aircraft and conventional submarines—worth almost Rs1.3 lakh crore for the Army and Rs1.4 lakh crore for the Navy. Under Atmanirbhar Bharat, the domestic industry will get contracts worth Rs4 lakh crore in seven years.

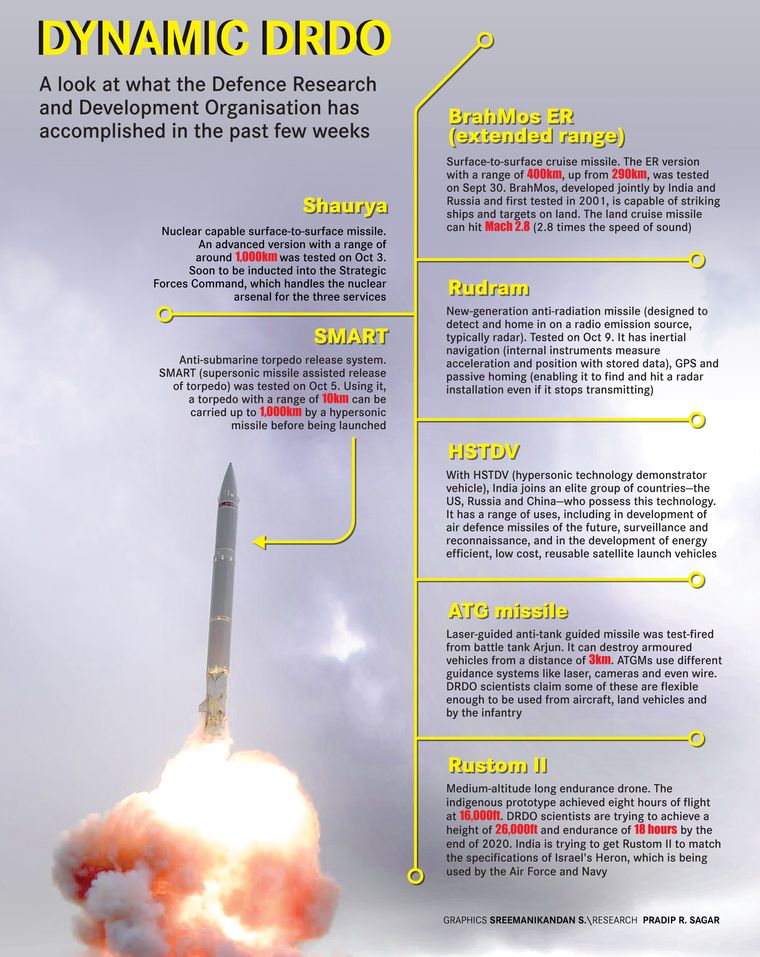

The Defence Research and Development Organisation has come out with a list of 108 systems and subsystems—including unmanned aerial vehicles, mobile decontamination units and marine rocket launchers—that it wants locally designed and manufactured. It has earmarked Rs100 crore to help the private sector, especially the nearly 6,000 micro, small and medium enterprises that supply products and components to defence behemoths. “This will help DRDO focus on more advanced technologies,” said DRDO chief Satheesh Reddy. “The industry will be a partner right from the beginning of all our projects.”

According to Laxman Behra, research fellow at the Institute for Defence Studies and Analyses, the government has simplified policies for private players. “In the next few years, the government will reap the benefit of these policy reforms,” he said. “Efforts are on to provide a level playing field to private players.”

Also read

- No 'Atmanirbharta' this, few takers for India’s rifles, pistols

- Indian Navy keeping strong vigil of Chinese vessel movements: Admiral Hari Kumar

- Mahatma Gandhi's ideas have answers to today's challenges, says PM Modi

- Vehicle scrappage policy to help attain Atmanirbhar Bharat: PM Modi

- Aero India to kick off with LCA Tejas deal

- UP steps up economic revival measures for MSMEs

With a well-defined policy and funding commitment in place, the focus is now on the acquisition process and the procedures to ensure ease of doing business. “The four waves of business process restructuring between 2018 and 2019 and the new draft defence acquisition process (DAP 2020) have focused on extensive involvement of the industry in its formulation,” said Jayant Damodar Patil, defence head, Larsen and Toubro. “[It] addresses all generic issues faced by the industry.”

Private players had built infrastructure, capability and capacity over the past few years. L&T, for instance, invested in establishing seven state-of-the-art centres for making weapon and armoured systems, warships and submarines, and missile, aerospace and military communication systems. The next logical step for the government, said Patil, is to expedite placement of orders.

“Programmes worth more than Rs4.1 lakh crore have already been granted acceptance of necessity (AON) by the defence ministry,” he said. “All that is needed is initiating issuance of RFPs (request for proposals) against the AONs, reviewing their progress periodically, and awarding [contracts] in a time-bound manner.”

Granting a level playing field for both public- and private-sector units would be crucial. The defence sector was first opened to private players in 2001, and each subsequent edition of the defence procurement procedure had added provisions to boost the domestic industry. But the complex policies and processes dampened enthusiasm.

The Atmanirbhar drive is expected to finally set things right. “Private players feel that there is still a continued bias towards public-sector undertakings,” Lt Gen (retd) Subroto Saha, member of the national security advisory board under the Prime Minister’s Office, told THE WEEK. “The prime minister’s initiative strives to bridge this gap in indigenisation and self-reliance with greater private-sector participation.”