On April 26, as the number of Covid-19 patients worldwide neared 30 lakh and deaths crossed two lakh, China reported just three new cases. The country’s National Health Commission said there were no new Covid-19 patients in Wuhan, the capital of Hubei province and the epicentre of the global pandemic. Bruce Aylward, assistant director-general of the World Health Organization (WHO), had earlier praised China for its “bold approach” that changed the course “of a rapidly escalating and deadly epidemic”.

As China prepares to go back to normal, Covid-19 is causing turmoil in the rest of the world. Several countries are furious, alleging that China delayed its response in Wuhan. French President Emmanuel Macron recently questioned China’s handling of the outbreak, saying things “happened that we don’t know about”. UK Foreign Secretary Dominic Raab said “hard questions” would have to be asked about the outbreak and “how it could have been stopped earlier”. US President Donald Trump branded the coronavirus as the “Chinese virus”, prompting China to term his tweet as “racist and xenophobic”.

A Delhi-based expert who did not wish to be named said China was at the centre of this international catastrophe because it delayed sharing information about the outbreak in the first few weeks of the epidemic, and punished doctors and journalists who spoke out. The WHO, said the expert, downplayed the dangers—in effect exposing the rest of the world to the virus.

On December 31, China informed the WHO of the mysterious pneumonia cases in Wuhan. This was the first official notice by the authorities, even though local transmission of the virus had begun much earlier. Doctors in Wuhan were reportedly aware that there was a deadly new virus that could cause SARS-like symptoms and spread from humans to humans. Li Wenliang, an ophthalmologist in Wuhan, had informed his colleagues in December that seven patients in his hospital had caught the virus.

“But China,” said the Delhi-based expert, “would not acknowledge the presence of a disease that was spreading rapidly; it threatened whistleblowers with arrest if they spoke about it.”

The WHO initially parroted China’s stand that there was no human-to-human transmission. “Preliminary investigations by Chinese authorities have found no clear evidence of human-to-human transmission of the novel coronavirus,” the WHO tweeted on January 14, a day after the first Covid-19 case outside China was reported in Thailand.

The health body also chose to disregard warnings from the Taiwan Centers for Disease Control, which had communicated the possibility of human-to-human transmission to both the WHO and China in December itself. “Owing to its experience with the SARS epidemic in 2003, Taiwan vigilantly kept track of information about the new outbreak,” said the Taiwan CDS. “On December 31, 2019, Taiwan sent an email… informing the WHO of its understanding of the disease. In the email, we took pains to refer to atypical pneumonia, and specifically noted that patients had been isolated for treatment. Public health professionals could discern from this wording that there was a real possibility of human-to-human transmission of the disease. However, in response to our inquiries, [the WHO only sent] a short message stating that Taiwan’s information had been forwarded to experts.”

China confirmed human-to-human transmission only on January 20. Two days later, the WHO issued a statement reconfirming it. It took eight more days for the WHO to classify the outbreak as a “public health emergency of international concern”. By then, there were more than 7,000 confirmed cases worldwide, with 82 cases reported in 18 countries other than China. On March 11, when the WHO declared Covid-19 a pandemic, the virus had spread to more than 100 countries, killing more than 10,000 people and infecting more than one lakh.

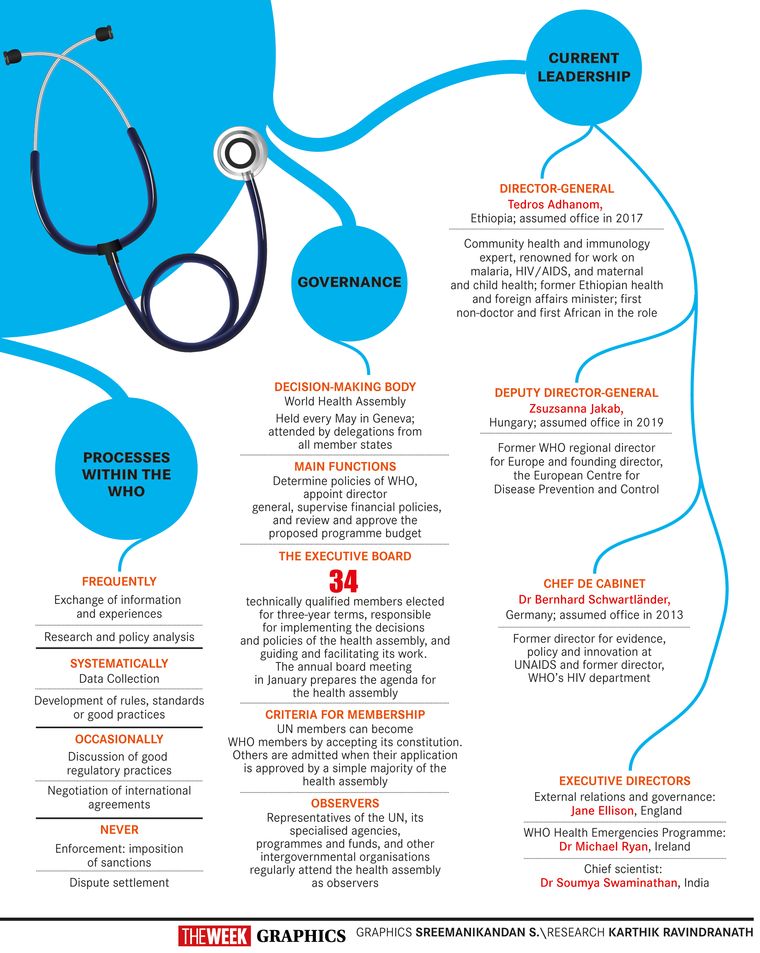

Despite China’s failures, WHO director-general Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus has been all praise for Beijing. On January 28, after meeting with Chinese President Xi Jinping, Tedros commended China “for setting a new standard for outbreak control”.

Kriti Kapur, who is part of the Observer Research Foundation’s Health Initiative in the Sustainable Development programme, said the WHO continued to praise China for its “transparency” and “commitment” even as allegations of negligence against the country grew. “The WHO’s sluggish response and its biased attitude towards China have sparked conversations regarding its credibility and the inability of Tedros to carry the mantle,” she said. “In December 2015, SARS-coronavirus diseases were declared a high-priority disease, requiring urgent research and development [of treatment]. The WHO pegged coronaviruses as one of the emerging diseases likely to cause major epidemics, an assessment which was reiterated in the 2018 annual review of prioritised diseases. But in 2019, when SARS-CoV-2 appeared to have spread among humans, there was no timely call to action.”

Yeshi Choedon, professor at Jawaharlal Nehru University’s School of International Studies in Delhi, agreed. “During the SARS outbreak of 2003, the WHO director-general condemned China for not giving the right information,” she said. “At that time, the WHO could send its own scientists to investigate and take proactive action. Whereas this time, Tedros was completely under the influence of China. By not getting the required information despite an alert by Taiwan, the WHO continued to dance to China’s tune.”

On February 3, when many countries were starting to impose restrictions on travellers from China, Tedros said there was no need for travel bans that “unnecessarily interfere with international trade”. “Several countries that denied entry of travellers, or those that have suspended flights to and from China or other affected countries, are now reporting cases of Covid-19,” stated the WHO.

It reiterated its opposition to travel and trade restrictions on February 29, barely two weeks before it declared Covid-19 a pandemic. “Far from acting as the nodal agency to coordinate a global response to this pandemic, the WHO became acquiescent to Chinese interests, losing credibility in the eyes of its other member states,” said a public health expert associated with a Sydney-based research institute.

He pointed out the WHO’s contradictory statements about the nature of the virus and the manner in which the disease is transmitted. “It first said that human-to-human transmission [happened] via respiratory droplets, as the virus cannot survive in the air. It was proven wrong. The WHO also underplayed the importance of wearing masks, insisting initially that only those caring for Covid patients and the patients themselves need wear it. Again, this was proven wrong,” said Vikash Keshri, a public health expert in Delhi.

On April 14, Trump accused the WHO of “severely mismanaging and covering up” the threat, and announced his decision to freeze funding to the organisation pending a 60-day investigation. The Australian government, too, proposed an independent, international inquiry on the origin and handling of the Covid-19 crisis, including the WHO’s role in it.

Critics say Tedros himself has been complicit in China’s underreporting of the crisis. An Ethiopian microbiologist, Tedros is the first non-medical doctor to head the organisation. He began his career as a public health expert in the 1980s, when Ethiopia was ruled by the Derg, a Marxist-Leninist military junta. When the Derg government fell, Tedros went to London for higher studies. He returned to Ethiopia in 2001, and was minister of health from 2005 to 2012 and minister of foreign affairs from 2012 to 2016. He has been the WHO director-general since 2017.

According to Abhijit Iyer-Mitra, senior fellow at the Institute of Peace and Conflict Studies, Tedros is “extremely adept at social manoeuvring and coopting people”. “He has a long history with China, going back to his days as health minister,” said Iyer-Mitra. “China used to protect Ethiopia in the UN Security Council for its human rights violations. Tedros was Ethiopia’s foreign minister then. So how can he be trusted to evaluate China’s Covid response properly?”

With right-wing populism holding sway in the US and Europe, the west has been slowly withdrawing from the international organisations that they had helped found. This has led to China increasing its grip on the WHO and other UN agencies. “Tedros was appointed in the first place because the US couldn’t care less, and China wanted to establish its presence,” said Choedon.

Tedros says he is being hounded. In April, he said he had been subjected to racist comments and death threats for several months. He alleged that the abuse had originated from Taiwan, and the Taiwanese foreign ministry “did not dissociate” from it. Taiwan, which had earlier accused the WHO of denying it vital information regarding the virus, responded to Tedros’s allegation by stating that it opposed any form of discrimination. It also invited him to visit the island. Accepting the invitation would anger China, which considers Taiwan to be a breakaway province and has kept it out of the UN system.

Tedros is under immense pressure, but he has received support from a number of international leaders and health care organisations. Cyril Ramaphosa, South African president and chairman of the African Union, said “the temptation to apportion blame” should be avoided at this time of crisis.

“The WHO is an intergovernmental body that has historically played a major role in developing the Health for All project, and is legitimate and more democratic than other global health institutions,” said Susana Barria, a Delhi-based public health expert. “At this time of pandemic, its role needs urgent strengthening, and not the sort of undermining that the US is up to.”

But critics say the first step in strengthening the WHO is to study its failures. “The single-most important question to be asked is, why were WHO officials not given access to ground zero of the epidemic in China until the end of January, when Tedros met with Xi?” asked Choedon. “And why did the WHO not make an effort to independently verify Chinese claims?”

The answer, according to Sundararaman T., former professor at the School of Health Systems Studies at the Tata Institute of Social Sciences, is that the WHO does not conduct voluntary investigations. “It is quite likely that the Chinese underreported the extent of the epidemic,” he said. “But the WHO is only an advisory body that has limitations imposed on it by member states. It cannot barge into countries and force governments to give out information.”

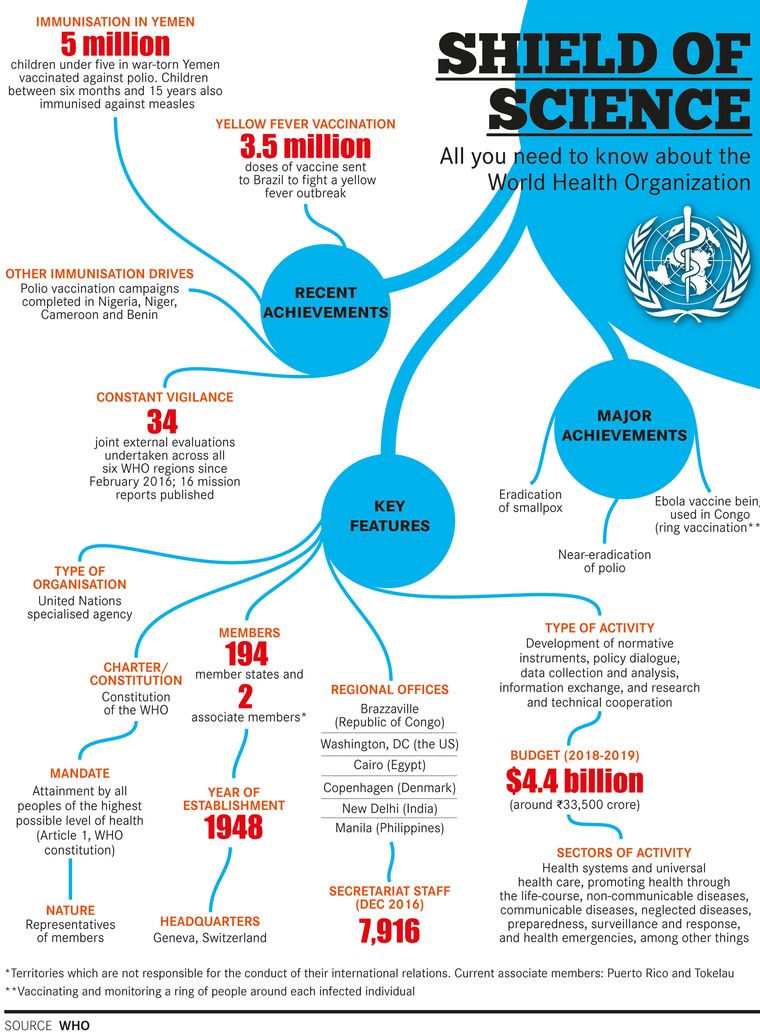

Set up by the United Nations in 1948 and headquartered in Geneva, the WHO is an intergovernmental organisation comprising 194 member states. It has the broad mandate to coordinate international health policy and set guidelines to promote coordinated medical responses in an increasingly interconnected world. Some of its biggest achievements are the eradication of smallpox, global immunisation programmes against polio, measles and tetanus, and management of AIDS.

“The problems with the WHO are the problems created by the US dominance of it,” said Sundararaman. “All appointments and all key policy documents, statements and resolutions require a US sign-off. And the US has been cutting its funding from the eighties. The most important thing is that, on matters regarding commodities, intellectual property rights and technology, the WHO has been closer to US positions than to low- and middle-income nations. A lot of the staff is from the US; a lot of funding is from US corporations, directly or indirectly. The WHO is under the thumb of the US, but the latter continues to make a scapegoat of the organisation.”

Joseph S. Nye, professor at Harvard University’s John F. Kennedy School of Government, said member states had left the WHO high and dry. “For years, states have failed to provide the WHO with adequate resources or authority to carry out its missions,” he told THE WEEK. “At the same time, the WHO’s bureaucracy has been overly solicitous to important member governments such as China. The initial reaction of both Trump and Chinese President Xi Jinping was denial. Crucial time for testing and containment was wasted, and the opportunity for international cooperation was squandered.”

A major factor restricting the WHO’s autonomy is its funding system. Funds are split into two categories: Mandatory contributions from member countries, which are determined by each country’s income level and population; and voluntary contributions from member states and nongovernmental organisations. In recent years, philanthropic bodies such as the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation have emerged as major voluntary donors.

The first category makes up around 20 per cent of the WHO’s total budget. The organisation is free to spend funds in this category on any programme or activity. Voluntary contributions, which make up the remaining 80 per cent, can only be spent on programmes or activities chosen by the donors. This means programmes that are vital to the WHO’s mandate remain perennially underfunded.

Also, these programmes often clash with the interests of big donors like the US. “The US government is the single largest donor, contributing as much as 20 per cent of the WHO’s total budget,” said Sundararaman. “US-based corporations and global health institutions make up another large chunk of contributions. This is why most of the WHO’s resolutions have to be compatible with the geopolitical stances of the US. The latter also has de facto veto power.”

Mark Lurie, associate professor of epidemiology at Brown University’s School of Public Health, said Trump’s decision to freeze funding was a bit like tossing the skipper overboard when the ship starts to sink. “A few years ago, Trump eliminated his own office of pandemic preparedness, and for years, he has proposed major cuts to the National Institutes of Health, the Centers for Disease Control and the US Agency for International Development—the very organisations that are best prepared to respond to global health emergencies,” Lurie told THE WEEK. “So it is not a surprise that we are lacking critical resources.”

On April 14, as Prime Minister Narendra Modi extended the lockdown in India to May 3, the WHO lauded India’s “tough and timely actions” against the pandemic. This was a marked shift from the organisation’s stance a month earlier. Mike Ryan, executive director of the WHO’s Health Emergencies Programme, had criticised India for banning the entry of foreign nationals. “Blanket travel measures in their own right will do nothing to protect individual states,” he had said on March 13.

India’s relationship with the WHO, however, has largely been synergetic. The organisation has been instrumental in eradicating smallpox and polio from India, and has been working to contain the spread of AIDS since 2000. To contain Covid-19, it has been working closely with India’s health ministry in surveillance and contact tracing, and diagnosis and risk mitigation. “The WHO’s primary role is to provide technical support to the Indian government and the Indian Council of Medical Research,” said Oommen C. Kurian, head of health initiative at the Observer Research Foundation. “It happens through joint monitoring group meetings and empowered groups. They have expertise and training to offer, but no budget.”

Despite its limitations, though, the WHO remains the only multilateral body that helps low- and middle-income countries fight major public health challenges. For this reason alone, it needs to be supported and not undermined, said Choedon. “In the middle of this pandemic, they are the people who are ensuring that the third world has better access to essential commodities, preventing the development of monopolies in essential commodities, and promoting collaborative research, through which all can access the new treatments for Covid-19,” she said.

It is clear, though, that the WHO needs a comprehensive makeover. “In the post Covid-19 era, the WHO has to be a much more independent entity with a mind of its own,” said Abhijit Das, clinical associate professor at the University of Washington in Seattle. “But whether it will become that, remains to be seen.”