It was March 2016. Mandeep Mann―then a young management graduate-turned-IT professional, ambitious and enterprising, an adventure junkie and fitness freak―had just parked his car in the parking lot when he chanced upon a blood donation drive poster. Mann had always been an eager volunteer. At 36, he had donated at least 20 times, if not more.

As someone in a leadership role in a reputed IT firm, he had his plate full. Still, he took out time to donate blood yet again. Just as he was leaving from the blood donation centre for work, a volunteer from the DKMS-BMST Foundation India, an NGO focusing on fighting blood cancer, asked if he would like to consider donating his stem cells, too, “because that way you could save lives of those suffering from life-threatening blood disorders and cancer”. Of all the things she said, the word ‘cancer’ stuck with him. It had been a year since his wife had been diagnosed with breast cancer. They had met through common friends and Mann was besotted by her zest for life and charm. But now ever since the diagnosis, he could see her energy ebbing away. Though he had never heard of stem cells before nor had an idea of what he was in for, he knew he had to do anything that could potentially save someone from cancer’s grip. He signed up. They took his cheek swab sample, exactly the way it is done for Covid-19 testing. After an examination of his sample, Mann entered DKMS-BMST’s global registry of potential stem cell donors. This meant that he would be able to donate his healthy blood stem cells to a cancer patient whose blood cells were all infected. These healthy blood cells will then multiply and grow in a cancer patient’s body, thereby giving a fresh lease of life to someone who otherwise had no chance of survival.

Mann was given a donor ID card with a strangely unique number that ended with -007, making him feel like James Bond. In the global donor pool of the World Marrow Donor Association, a global database of volunteer donors, Mann was already a potential lifesaver-in-waiting. But, for Mann, it was just another act of kindness.

That night in 2016, as Mann went to bed with his heart full and mind at peace, several thousand kilometres away in Giana, a small village in Punjab’s Bhatinda, Mandeep Singh―eight years younger and a stranger to Mann―remained wide awake. Sleep did not come easy to him ever since blood cancer came into his life, eating into his body like an unforgiving termite bent on finishing him up.

But some seven years before that 2016 night, life was different for both Mandeeps. It was June 2009. Mann was in Bengaluru―his career was going great and relationship was blooming. He had just completed a year in marriage; weekdays he worked hard and weekends his wife and he would set out on getaways. In Giana, Singh was just 20―cheerful, well-built and athletic and excited about the possibilities life had to offer. Eldest of three siblings in a happy family that primarily depended on farming for a living, Singh dreamt of a career in khaki. A star kabaddi player in college, he had just aced his training rounds for police recruitment. To celebrate, he had planned a bike trip with friends. That’s when Singh was bogged down by a “sudden fever that refused to budge; it went on for months”.

At the time Singh’s total leukocyte count―the white blood cells count―was close to 3.5 lakh per microlitre; the normal range is between 4,500 to 11,000 per microlitre. Clearly, something was wrong. A battery of tests and a bone marrow biopsy revealed chronic myeloid leukaemia. CML is a type of blood cancer that can lead to the formation of immature or abnormal blood forming cells called cancer cells, which enter the bloodstream and multiply in an uncontrolled way, thereby driving out healthy cells. As a result, the blood can no longer perform its basic tasks, such as transporting oxygen and protecting the body from infection.

In many cases, with medicines like Imatinib (Glivec), which then cost Rs40,000 per strip (that would come to more than Rs1 lakh per month), the disease progresses slowly. But Singh would skip his dose, especially in the first two years, as he wasn’t told about the deadly nature of his disease. His doting father, Naib Singh, had kept it from him, thinking he would be devastated. It was only when Singh sneaked into his father’s room, switched on the call recording option on his father’s phone and heard the recorded conversation between his father and brother-in-law the next day that the severity of the situation dawned on Singh. He cried himself to sleep that night. “Until then, I had just thought it was any other ailment, which will heal in time,” says Singh in a telephonic conversation with THE WEEK. “I used to keep missing my dosages, despite the doctor’s strict warnings that I had to pop a pill every single day for lifetime. That’s why I quickly went downhill.”

But Naib was too protective of his son and did not want to see him lose heart. Those days, the family had seen a large number of people from their neighbourhood die of cancer, including children. His mind would keep going back to Punjab’s infamous cancer trains that would ferry patients from Bhatinda to the Acharya Tulsi Regional Cancer Treatment & Research Institute in Bikaner, Rajasthan, “hoping to get treated at a low cost or die trying”. Seeing his son board that train was Naib’s worst nightmare.

At the time, it was found that emissions of soot and fly ash from the three coal-based thermal power stations, rampant use of pesticides, high amounts of uranium seeping in borewells and polluted water used for growing rice crops and drinking had rendered villages of Punjab dangerous to live. “Researchers had made a shocking discovery of the presence of uranium in children way above safety limits,” writes Dr Sona Sharma, author of Mandeep Meets Mandeep, which chronicles the journey of two strangers who come together to forge a bond of a lifetime. “The place had become a boiling cauldron of dangerous chemicals, each more carcinogenic than the other.”

Cut to 2017. Life had been moving in a pattern for both the Mandeeps. Mann was building his startup and climbing up the ladder, whereas Singh was feeling better, both physically and mentally. He spent time with friends, had even tried his hand as an Uber driver in Chandigarh, had attended a friend’s wedding and was now back in his village to work on the farm. “My friends by then had moved out of the village for work; many had married,” recalls Singh. “Marriage was, of course, not on my wish-list at that time. I was only grateful to be alive with the morbid fear of cancer behind me.”

And then, cancer gave its cue once again―that insidious pain he had experienced the first time had returned to haunt him. “Just when life had begun to look brighter, I was being sucked into this black hole for a second time and this time I was exasperated and devoid of all hope,” recalls Singh. “It was depressing, especially since we had spent so much money already, had sold off our land, pulled through trying tests only to end up at square one.”

Until then Imatinib had prevented the increase of BCR-ABL1, the abnormal gene found in CML patients. But after a point the medicine no longer worked and the disease progressed, and he moved to the “accelerated phase”. That was the first time Singh was told about a stem cell transplant.

“By then Singh had crossed from stage 1 to stage 3 (acute) and there was no way he could have been cured without a bone marrow transplant,” says Dr Dinesh Bhurani, director, haemato-oncology and bone marrow transplant, Rajiv Gandhi Cancer Institute and Research Centre, New Delhi, who treated Singh in his later stages of cancer. “All his cells were infected and rogue. His body had to get a set of fresh blood with healthy cells and that too very fast because there was rapid deterioration.” Bhurani put Singh on chemotherapy and tablets and began the hunt for a suitable donor.

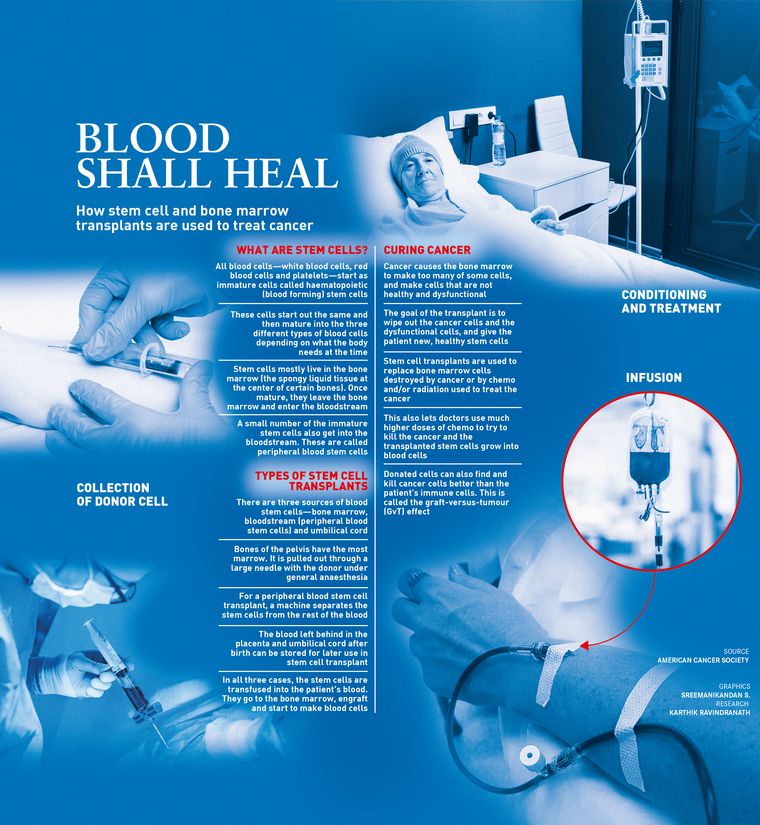

Usually, stem cell transplants are done to replace bone marrow cells that have been destroyed by cancer or chemo or radiation. In some cases where the transplant uses stem cells from another person, it can help treat the cancer by finding and killing cancer cells even as replenishing the bone marrow with healthy cells. That is what was essential in Singh’s case, and for that he needed a matching donor.

A suitable donor is the one who has a matching HLA type. HLAs (human leukocyte antigens) are protein markers found on the surface of most cells in our body, including white blood cells. They are markers which help the immune system in recognising its own body cells from foreign cells. So that means only those cells that have protein markers similar to the patient’s can be transferred, or else the immune system will reject them. So, if two people share the same HLA type, they are considered a match. Even in one’s own immediate family, the chances of finding a donor are one in four, say experts. Unfortunately, none of Singh’s close family―father, brother Jagdeep, sister Soma―was the right match. Now the only option was to look for a potential ‘stranger donor’ in stem cell registries. “At that time, I was staring death in the face,” says Singh. “I was so desperate that I was trying all sorts of alternative treatments, including ayurveda and blind faith.” He waited for a donor for three years. He got potential donors twice, but both backed out at the last minute.

“The problem in India is that people register voluntarily, but when the time comes to donate and actually help a patient, about 70 per cent refuse,” says Patrick Paul, CEO, DKMS-BMST Foundation India. “One of the most concerning aspects is that young people in this country, who are potential donors, are not able to make their own decisions and opt out of the process if their families say no.” The lack of awareness and ignorance of stem cell transplants and its impact have resulted in a minuscule number of people registering as stem cell donors. “Some absurd reasons include signing up for this might lead to infertility or the loss of an organ. But we try to educate and counsel people to be donors,” says Paul.

Globally, around 41 million people are registered as stem cell donors from multiple registries, while India’s contribution is only 6 lakh. DKMS alone has 12 million stem cell donors globally, with a little over one lakh from India. “And given that the probability of finding a match is very rare―one in a million―of the one lakh in India, only 110 people have actually gone ahead and donated stem cells,” says Aarohi Tripathy, public relations manager, DKMS-BMST Foundation India.

As per a research paper published last year in the International Journal of Clinical and Medical Education Research, Ajeet Kumar from the Centre for Genetic Disorders, Institute of Science, Benaras Hindu University, writes, “India’s annual incidence of CML ranged from 0.8 to 2.2 per one lakh people. This is the most frequent type of leukaemia in India, accounting for 30 per cent to 60 per cent of all leukaemia.” A lot of people who die of blood cancer in India are not even aware they had blood cancer, adds Paul. “Every five minutes, someone in India is diagnosed with blood cancer, and an estimated 70,000 people die every year because of blood cancer,” he says.

In her book, Sharma writes about a young CML patient dying after a donor backed out at the last minute. The child had been given excessive chemotherapy to prime his body to receive the stem cells. The body became so drained and vulnerable that he died within hours. Another case was of a little girl who had matched with multiple potential donors, but each one of them had backed out. “At times, a registered person refuses to go ahead with the donation unless they know the caste and religion of the patient,” says Tripathy. “This is specific to India. However, as a policy, we do not share details of either the patient or the donor.”

By now it was 2018-19. Mann was struggling with his wife’s metastatic cancer treatment with multiple rounds of chemo, and Singh had gone from being a bright young college student to a patient in his 30s with no sign of a normal future.

“Every day, for those three years, I prayed to God to somehow magically make that one person from any corner of the world appear in front of me, whose stem cells my body would accept and embrace wholeheartedly; someone who had been kind enough to register as a donor so that I could get a fresh lease of life,” says Singh. “I would be indebted to that person for my entire life.”

And then, ID number ‘-007’ serendipitously appeared. Mann was a 100 per cent match. Unlike now, one could not go ahead with a transplant with 50 per cent or 25 per cent match then. “It is sheer good luck and a blessing if a patient can find a 100 per cent match. And that too one from within the same country and in this case the same ancestry; [it] is quite magical,” says Sharma.

All transplant physicians and hospitals have been given a platform―Hap-E Search―wherein they just enter the HLA profile number of the patient to check for a suitable donor match. The physician then contacts the registry with the donor ID. A donor’s details are never revealed; he or she is only a number. Their names and other details are not given out ever or at least until two years post transplant if it is successful. That is how Mann remained Singh’s James Bond until the two met in 2023, four years post Singh’s transplant.

But in 2019, when Mann was contacted for the stem cell donation, he wasn’t quite sure. He already had too many things on his mind. But his “yes” was crucial for Singh, who had been struggling with CML for 10 years now. In time and after consulting his wife, Mann was in. He would not go back on his word. “We have got to spread kindness around, that’s what makes us human,” he had said then. “If I can be someone’s miracle, why not?”

Mann gave a sample for the pre-donation confirmatory test. After his reports were marked okay, he had to get G-CSF (granulocyte colony-stimulating factor) injections for five days. These would help in increasing the number of stem cells in his blood, which would, in turn, help Singh get sufficient quantity. Mann was told that there could be nausea, fatigue and headache post procedure. He was asked to refrain from alcohol, late-night partying, vigorous exercises and was advised to drink lots of fluids.

Early morning on December 27, 2019, Mann was shown into a comfortable room at the BMST centre in Bengaluru. His vital signs were tracked and sterile needles were inserted in both his arms. The blood would be drawn from one arm and it will pass through a small apparatus that would collect his stem cells and the rest will be routed back to the body via the needle in the other arm. The process―apheresis―is akin to the way in which platelets are collected for dengue patients. Three to four hours and two movies later, Mann was back home. Stem cells were collected from his blood and were given to the hospital for the transplant. Mann did not drink alcohol for two days after that. “I was feeling great,” he tells THE WEEK. “It was liberating really to know that you have that one divine set of cells inside your body that can bring a person back from the grasp of death. This one time I was really amazed at how science could trump death, too.” That night, he hung out with friends, with good food and music for company.

In Giana, Singh was counting days when the cells would reach him, akin to the excitement one has when one has placed an order online and impatiently waits for the delivery. Ever since he had received the news that his blood stem cell transplant could happen soon, he was thrilled “like a child”. That January of 2020, he had danced his heart out at his best friend’s wedding procession. “By then I hadn’t even received the news and healthy cells, but I had already begun to look at life with a refined perspective,” recalls Singh. “I did not take anything for granted anymore. Everyone and everything I had became so much more precious and pronounced now. It was a fantastic feeling.”

Prior to the transplant, Singh was informed that it did not give a 100 per cent guarantee of cure. He was given tablets and chemotherapy to kill all cancer cells. That quite drained him―he was now bald, nauseous, dizzy and tired. That day, Singh broke down as he saw lumps of hair fall off as he touched them. His heart sank. Until now, he had been hopeful, but in the condition he found himself that day, his confidence had been crushed.

Next day, a fresh set of stem cells were transplanted into his frail body. His body had no ability to fight off infections while the transplanted cells took root. If cancer didn’t kill them, an uncontrolled infection could. “But that was managed with medicines. The main problem was that Singh got the graft versus host disease, which is a systemic disorder that occurs when the graft's immune cells (that is Mann’s cells) recognise the host (Singh) as foreign and attack the recipient's healthy body cells,” explains Bhurani. “This meant his body was at war with the donor cells. In simple terms, Mann’s cells were not ready to accept Singh’s body as their own. The latter was covered with rashes. This is a life-threatening complication, but Singh sailed through with the help of Ponatinib, which took care of his infections, too.”

Within days, the new stem cells began producing healthy blood cells, and Singh began feeling better. He was asked to live in a “bubble” until declared fit to move. But the very next day, Singh was driving back to Giana with his sister and brother-in-law. His parents had arranged a prayer ceremony, “which was to be attended by the entire village as a way of expressing gratitude to the universe for finding him his ‘angel twin’ who had blessed him with a healthy life”.

“Many keep waiting for years in search of a matching donor,” says Bhurani. “I have seen so many of them die for the lack of funds to pay international stem cell registries that charge high rates, even when a donor is available and ready for a transplant.” In Singh’s case, DKMS charged Rs 5 lakh for the process. Add to that the transplant cost, which goes up to Rs20 lakh. Many cannot afford the procedure. In Singh’s case, the entire amount was paid by the family. “What worked for the two, which was found later, was that they unknowingly shared the same ancestry,” says Bhurani. “They are now genetic twins of sorts.”

Singh had not forgotten the registry rule―direct interaction between the donor and the patient was prohibited till two years after the patient’s recovery. He had been waiting desperately to meet his “god”. His wish was answered by the DKMS team―the two were to meet at a coffee shop in Bengaluru in February 2023. Singh had finally crossed the two-year mark, and could now safely call himself “cured”. He repeated the word to himself like a child, over and over again.

From as much as she had gathered from her past interactions, Tripathy says, “Both the men, I remember, were so different and yet similar in so many ways. Both were good-looking, tall Punjabis. Both were very warm, polite and easy-going. It was exciting to see how they would meet each other.”

At the café, Mann had taken the seat that faced the other way, so he did not see Singh arrive. When Singh, already teary-eyed but with sheer happiness, walked in, he tapped Mann on the shoulder and said, “Hi, I am Mandeep.” And Singh then immediately hugged him tight. “Thank you,” he added. Those were the only words spoken in that interaction. “What could I say? So much had been felt there was no room for words,” recalls Mann.

They didn’t need to spell it out; they knew they were bound for life―the two often meet whenever Mann visits Punjab to meet his sister in Jalandhar.

People who wish to register can visit https://www.dkms-bmst.org/get-involved/become-a-donor