Anshul Shukla, 27, from Lucknow talks about his turbulent past almost dispassionately.

While doing his graduation, he had bouts of depression and changed his major four times. He started with engineering—first mechanical and then electronics—and later switched to humanities—English and Economics. During his graduation in Economics at Shiv Nadar University, he was suspended for violence, and he dropped out of college. “I had just come back from a month-long trip from northern Thailand, and I was feeling upbeat, energetic and very happy. It was showing in my behaviour,” recalls Shukla. “Earlier, I was feeling very depressed. I got into a fight and unfortunately I became a bit violent.”

The incident changed the course of his life. At 21, he was diagnosed with bipolar disorder (BD) by the psychiatrists at the university. He has had a bipolar depression crash twice following manic episodes (a state of mind characterised by euphoria, high energy and excitement). “During the manic phase of bipolar, I would feel on top of the world,” says Shukla. “My confidence was unshakable and I felt I could achieve anything. This would be followed by a state when I would feel suicidal and empty. Like everything was being taken away from me.”

Sometimes he would experience psychosis (a severe mental disorder wherein the patient loses touch with reality) and have delusions about his parents trying to harm him. “Things got so bad that the police had to be called in and I was taken in an ambulance to hospital. Such incidents have happened twice or thrice,” says Shukla.

Shukla finally completed his graduation and did his masters in Political Science from Indira Gandhi National Open University. But he is still struggling to keep a job. He never disclosed his ailment at any of his previous organisations for fear of discrimination and losing the job. “I still didn’t manage to stay at a job for more than three months,” he recalls. “I’m finding it difficult to focus on work or further education, because I can’t seem to stick to anything.”

The world is often unkind to people with mental health issues. At times, the hostility begins at home. “Most of my relatives don’t even think that this is a real thing,” says Shukla. “They think I’m lazy and don’t want to work and that is why I am making up such excuses. But my family supports me a lot.’’

Shukla’s maternal grandfather supposedly had bipolar disorder. “He used to take lithium,” says Shukla. “He used to get manic and sometimes come back home without clothes as he would give them away to strangers who needed them more.”

Shukla is currently on lithium and a long-acting depot injection. He had been on different medicines earlier. He switched to the current combination after the previous medicines stopped working for him.

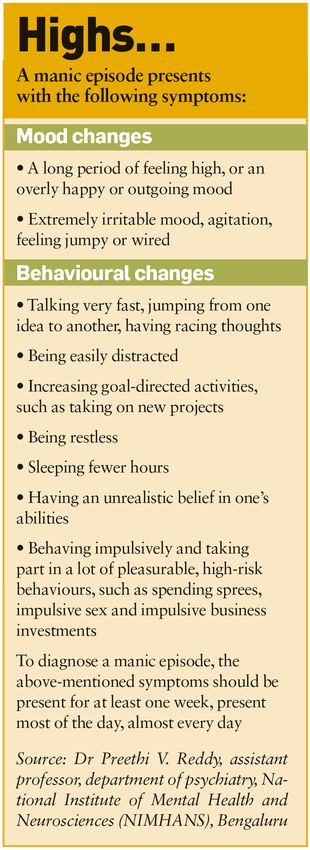

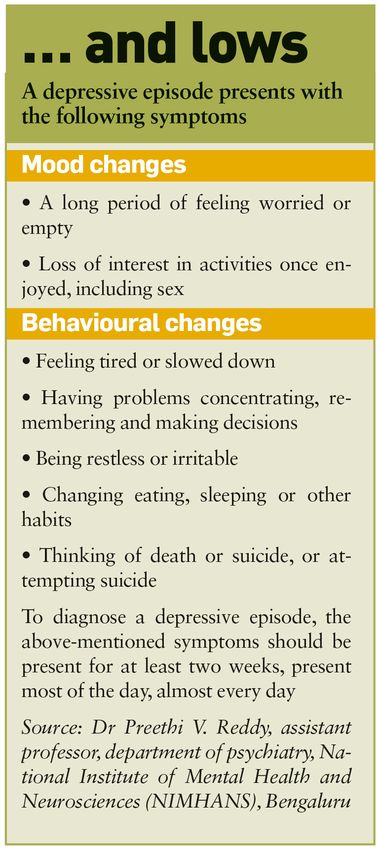

The term ‘bipolar’ refers to the way one’s mood can change pathologically between two very different states of excessive happiness and sadness—mania and depression, explains Dr Muralidharan K., medical superintendent and professor of psychiatry at the National Institute of Mental Health and Neurosciences (NIMHANS), Bengaluru. “In manic episodes, someone might feel very happy, irritable, or ‘up’, and there is a marked increase in the activity level,” he elaborates. “In depressive episodes, someone might feel sad most of the time, indifferent or hopeless, in combination with a very low activity level.” The mood changes that people with bipolar disorder experience are different from the usual mood swings. “It is a brain disorder that causes unusual pathological shifts in mood, energy, activity levels and the ability to carry out day-to-day tasks, that last a few weeks to months, continuously,” says Muralidharan.

People with bipolar disorder swing between both ends of the spectrum, that too without any apparent reason or trigger. “These changes are episodic in nature,” says Dr Preethi V. Reddy, assistant professor of psychiatry at NIMHANS. “The range of mood changes can be extreme, with the episodes being of two opposite polarities.”

Abhishek Mehta, 28, from Gandhinagar, is a worried man these days. He is unemployed, not for lack of trying. “I tried as many as 12 jobs, but couldn’t survive anywhere,” says the business management graduate. He tried his hand at varied jobs like customer service, finance, IT recruitment, but had no luck. “I used to get panic attacks and repeated bouts of depression and anxiety,” says Mehta. “I would have bipolar mania and paranoia (irrational suspicion, mistrust of people and a fear that someone is out to get you and conspiring against you) as well. All these took a toll on my professional life.” He has had panic attacks but never mania with psychosis at work.

People with bipolar disorder may experience psychotic symptoms in depressive as well as manic phases. Mehta had false beliefs that he held persistently. Delusions happened mostly in the manic phase of bipolar disorder, he says. Occasionally, he had hallucinations, too. “I would feel the ground was shaking,” he recalls. “Once, I saw my shadow moving while I was standing still. But mostly, it was delusions and paranoia.”

Mehta has no family history of bipolar disorder. Looking back, he says the turbulence of adolescence scarred him for life and perhaps acted as a trigger for his bipolar episodes. “There was a lot of bullying and abuse. I used to get teased for being overweight,” he says. “All that trauma kept building up. I was very sensitive and there was no way I could express my emotions. The brain and body can take only a certain amount of stress.”

Mehta then became quiet and withdrawn. He would often feel sad and dejected, and had a major breakdown in 2015. The bipolar depression with psychotic symptoms lasted two months. “I had delusions and I felt very impulsive,” he recalls. “I remember I lost a lot of weight prior to that…. Prior to the episode, I felt dizzy, too.” His mother—his pillar of support—took him to a psychiatrist and he was diagnosed with bipolar disorder. With medication, he is stable right now.

Mehta wants to work and be independent, but doesn’t know how. He thinks he would be a misfit in the corporate world. Bipolar disorder could affect every aspect of one’s life, says Mehta. “My girlfriend left me as I was not financially stable, though she knew about my mental health issues,” he says.

Bipolar disorder peaks between 17 and 30 years of age, says Dr Alok Kulkarni, senior consultant psychiatrist, Manas Institute of Mental Health. Even among the elderly diagnosed with bipolar disorder, it is very likely that the disorder would have started in young adulthood. It is quite rare to find new-onset bipolar disorder in the elderly, he says.

Across the world, the prevalence of bipolar disorder is equal in men and women. The National Mental Health Survey (NMHS) 2015-16 identified the prevalence to be 0.6 per cent in men and 0.4 per cent in women in India. The NMHS found that the prevalence was more in the urban population when compared to the rural population.

Prevalence of bipolar disorder in India is between 0.5 to 1.5 per cent, says Kulkarni. This means that, at any given point in time, 60-70 lakh Indians are living with bipolar disorder. These are staggering numbers for a country that has less than 9,000 psychiatrists for a population of 1.3 billion.

Access to psychiatric care had been a major challenge for Krishna, 25, from Uttar Pradesh. “There are very few psychiatrists in tier 2 and tier 3 cities,” he says. He now opts for online consultation.

Krishna, who works as a tutor for an EdTech company, was diagnosed with bipolar disorder at 17. He had his first manic episode while preparing for his IIT entrance exam. He had scored 91 per cent in his class 12 exams. “I was under tremendous pressure to prove my worth,” he says. He believes that people suffering from bipolar disorder or any mental illness can have a successful career if people around them are empathetic and have proper awareness. A huge fan of Dr A.P.J. Abdul Kalam, he dreams of launching a startup that will help students pursue their passion.

There are mainly two types of bipolar disorder—bipolar I and bipolar II. Bipolar I is when a person has one or more episodes of mania with an episode of depression in the past or vice-versa. In bipolar II, the patient will have episodes of hypomania, a less severe form of mania, with episodes of depression. People with hypomania tend to be cheerful and energetic. Hypomania is characterised by a decreased need for sleep. Even if the individual sleeps for just three or four hours, he/she will be fresh and active in the morning. There are no socio-occupational impairments or psychotic symptoms. Irritability is less common among people with hypomania. However, the depressive episodes in bipolar II episodes could be as severe as in bipolar I, says Dr Johann Philip, a consultant psychiatrist in Kochi.

Avantika B., 19, from Mumbai was diagnosed with bipolar II when she was 17. She experiences hypomania. “I sleep less, I eat less, and I think I am being productive but it is just a feeling. Being hyper makes me feel I am more productive but I’m not,” says Avantika, an undergraduate student of psychology at NMIMS, Mumbai. “I would be working 10 hours straight but it wouldn't really be as productive as when I am working 7 hours during my maintenance phase. I am able to work longer hours though because I tend to commit myself to more things when I am in hypomania.”

Avantika tries to go slow when she is in her depressive phase. “During depression, just making it to college is enough sometimes. It can get really suffocating and draining at times,” she says.

While there are other types of bipolar disorders like cyclothymia—highs and lows are not as extreme as in bipolar I and II—and unspecified bipolar disorder, they are relatively uncommon. “What we see in clinical practice conforms to bipolar I and II only,” says Dr Gagan Hans, associate professor of psychiatry at the All India Institute of Medical Sciences, Delhi.

Veena Malik, a 26-year-old filmmaker, musician and writer who grew up in Pune, describes hypomania as “an intense, elevated state where you can be extremely sharp, creative, and productive but can also be extremely angry, irritable and impulsive”. Malik, who has had recurring depressive episodes, was on medication for a year and a half.

It is important to differentiate between unipolar—characterised by either depressive or (more rarely) manic episodes but not both—and bipolar disorders to initiate the right treatment. Both disorders have strikingly different medication regimes and treatment approaches.

Varsha Verma, an engineering student from Kochi, would often fail to submit her assignments on time and perform poorly in her semester exams. She kept dropping out of her course as she was experiencing decreased energy levels, low mood, loss of appetite and poor sleep. Over 18 months, she approached several mental health experts, who put her on various antidepressants, but there was no slowing of symptoms. “On detailed evaluation, it was found that several past episodes of hypomania—discrete episodes of marginally elevated mood during which the patient was excessively upbeat, talkative, pleasant and spending too many hours in study without much sleep—were missed on her previous clinical evaluations. That changed her diagnosis from unipolar to bipolar depression,’’ says Philip, who treated her. He started her on a mood stabiliser and concurrent psychotherapy, which, he says, has helped her.

Antidepressants alone don’t work for most people with bipolar depression, explains Philip. “If antidepressants are given to a patient with bipolar depression, he or she may switch from depression to mania,” he says. “So it is very important to go through a clear history because the treatment approaches and medications are different for bipolar and unipolar depression.”

Bipolar disorder is more genetic than unipolar disorder, says Philip.

Long-term bipolar disorder can result in cognitive impairment leading to reduced cognitive functioning.

Bipolar disorder is rarely seen in children and adolescents compared to older adults. However, when it is present in this cohort, the elevated mood, restlessness and agitation associated with bipolar disorder is often mistaken for hyperactivity and wrongly diagnosed as Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder, says Philip.

Ashik Raj, 12, from Chennai had a diagnosis of ADHD that had worsened with medication before he consulted Philip. “On multidisciplinary assessment and after evaluating his symptom profile, we realised the diagnosis is not ADHD but childhood-onset bipolar disorder, which is now known to have a poor prognosis without early intervention and treatment,” says Philip. “ADHD is sometimes treated with stimulants that often worsen the symptoms of bipolar affective disorder. It is therefore prudent to accurately identify and treat bipolar illnesses as early as possible for improved overall treatment outcomes.”

Substance abuse is quite rampant among people with bipolar disorder. That complicates things in terms of treatment, says Philip. Individuals with bipolar disorder are also at an increased risk of suicide, possibly because of impulsive behaviour.

The mainstay of diagnosis in psychiatry is case history. There are no brain scans or lab tests to detect bipolar disorder. “We don’t have any diagnostic tests to confirm it. So we rely on a carefully taken history from the family members,” says Hans. Clinicians often use diagnostic manuals like the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders and International Classification of Diseases to diagnose bipolar disorder. “At the end of the day, the diagnosis is made based on clinical experience looking at the diagnostic criteria,” says Philip. Hans also observes the patient over a period of time. “If the symptoms are not clear, we insist the patient gets admitted so we can observe his/her behaviour and record the illnesses and problems,” he says.

Bipolar disorder is basically a mood disorder. “What we look at is a change in mood from the baseline,” says Philip. The baseline could be different for different people. “What is baseline for me could be mania for you. So it is important to look at the individual’s baseline,” he says. Assessment scales are also helpful for diagnosis and treatment. Young Mania Rating Scale, a 11-item interviewer-rated scale, is widely used to assess manic symptoms. Beck’s Depression Inventory, a 21-item inventory, is useful for evaluating the severity of depression. Philip uses these scales mostly to see whether the symptoms have subsided after starting treatment.

Compliance with medication is necessary to manage bipolar disorder. “Psychiatric medications take 4-6 weeks to have their effects,” says Hans. “Taking medicines on long-term basis is very repulsive for most patients. They take medications for a few days and the moment they feel better they stop. The effect of medications goes away in a few weeks and they may have a relapse. The more episodes you have, your prognosis worsens.”

Mehta is currently on medication. “I take anti-psychotics and antidepressants. They cost Rs500 a month. At one point I used to take 13 medicines. Back then, my parents spent around Rs3,000 a month on my medication”, he recalls.

Anti-psychotic medications decrease symptoms of mania and psychosis. “The right mix of medicines can help treat the symptoms really well and live a stable life. I see my doctor every month. And I’m also doing therapy,” says Mehta. Therapy costs around Rs1,500 an hour. “Medicines help with the chemical imbalance in the brain while therapy helps with the psychological aspects like thoughts, mindfulness and behaviour and coping mechanisms,” he says.

Also read

- 'Own your future': Experts at Mpowering Minds Summit urge women to master financial independence

- Mpowering Minds Summit: Masaba Gupta says women can have it all, but they have to stagger it

- Mpowering Minds Summit: Dr Harbeen Arora calls for women’s mental health to become a worldwide priority

- Mpowering Minds Summit: 'Menopause is not a disease, it's a new beginning,' says Dr Duru Shah

- Mpowering Minds Summit: How the quality of a child's earliest relationships determines future mental health

- Mpowering Minds Summit: Why we need to stop expecting motherhood to 'flow naturally'

Even people who experience just mania and no episodes of depression need treatment, says Hans. There is no cure for bipolar disorder. It is a chronic condition. “There can be multiple relapses,” says Hans. “You cannot say for sure which patients will have repeated episodes. It depends on several factors. There are patients who have had just one episode. At the onset, you cannot foretell whether other episodes will occur or not.”

Treatment-resistant depression often turns out to be bipolar depression. “One of the biggest controversies in psychiatry today is whether to prescribe antidepressants in bipolar depression or not,” says Philip. “Sometimes we do have to give a little antidepressant because they just don’t come out of depression otherwise.”

People process drugs differently depending on their genetic profile. White people seem to tolerate higher dosages than Asians, observes Philip. He recommends Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation for patients with treatment-resistant bipolar depression. TMS stimulates the left prefrontal cortex—responsible for mood regulation and positive emotions—and inhibits the right prefrontal cortex, associated with negative emotions.

For Malik, talk therapy has done wonders. She vented a lot before she learned to find some peace and stability.

Over the years, Avantika has learnt to live with bipolar disorder. She has made a lot of changes not just in her lifestyle but also at a cognitive level. Avantika believes it is really important to have a strong emotional support system and professional help to work through bipolar disorder. Her friends have been her pillars of support ever since she was diagnosed. “Sometimes it can get difficult to keep up with certain relationships when I have a depressive episode because not everyone understands it well; I wouldn't expect them to,” she says. “But sometimes it makes me feel invalidated or misunderstood. It's really important to have a strong emotional support system.” With therapy, she has been able to manage her life pretty well.

Therapy has been beneficial for Mehta, too. He feels more aligned with himself. He is part of Bipolar India, an online community that offers support for people with bipolar disorder.

Mehta feels bipolar disorder has made him a better human being. He now wants to spend the rest of his life helping others. “I love helping people going through mental health issues,” he says. “Even lending an empathetic ear helps keep their spirits up. I do it every day and it gives me immense joy.”

Some names have been changed.