As Khatera Hashmi smoothed the creases from her new salwar kameez—a confection in red and gold that she got for Eid—and arranged her daughter on her lap for a family portrait, a small frown appeared on her smooth brow. “I had told you, hadn't I? That you should wear a good dress, too, we will be having our pictures taken,” she said. “But you don't listen to me.”

Her husband, Mohammad Nabi, shrugged helplessly. “You are looking pretty, little Bahar has a new dress on, why bother about how I am looking?” replied Nabi.

Khatera, however, was not pacified. She knows he is wearing a faded tee and shabby shorts—his home clothes. She has smelt and felt them. Nabi looked at us sheepishly, as his wife gave him that wait-till-we-get-home expression.

Khatera is very image-conscious. How she appears to the world is very important for her, even though she can no longer see the world.

India came to know of Khatera's existence when she came to Delhi in 2020, a living testimony of the Taliban's brutality. The young woman in her thirties, who only months earlier had finished her training and joined the police force in Ghazni town, had immediately come on the Taliban's radar. At that time, the Taliban was a guerrilla force, the US troops were still in Afghanistan and Ashraf Ghani was heading the country.

They threatened her against continuing her job—it was not right for a woman to be working. The threats were dire enough for her superiors to suggest she take a transfer to Kabul. Nabi, who owned a cloth shop in the market, headed to Kabul, looking for an accommodation to rent. “It was the afternoon of June 6, 2020. I was walking back from my shift at the police station, which was very close to my house,” recounted Khatera in perfect Hindi. “Suddenly, three men emerged from a narrow lane—two were on a motorcycle, one was on foot. They began hitting me and the scarves they wore around their faces loosened, even as I fell to the ground. I had seen their faces.” That was the last thing Khatera ever saw. She blacked out in pain. The men, ostensibly afraid they would be identified, simply gouged out her eyes with some sharp weapon—no one knows what it was.

“I was reading the namaz when I got a call from Khatera's friend, saying she was attacked,” recalled Nabi, his Hindi heavily accented and liberally sprinkled with Pashto. “I thought it was a joke and went back to reading the namaz. But then I began feeling uneasy and I called her again. And my world crashed around me.”

Khatera was shunted from hospitals in Ghazni to Kabul. She had injuries all over, but her face was the most battered. “I didn't think she would survive,” said Nabi. She did, however. And as she recovered, her family dreaded telling her the truth. Around 12 days later, when her injuries were healing, she realised that as the bandage slipped from her eyes, her lids seemed stuck together—they weren't opening. “I realised I couldn't see,” she recalled that moment in a surprisingly composed voice. “Vo din mere liye bahut sakth tha [it was a very difficult day for me].”

What Khatera was not to know was that even her eyelids were mutilated. It has taken several painstaking surgeries by the doctors at Dr Shroff’s Charity Eye Hospital in Delhi's Daryaganj to bring back the beauty of her face. Only, the light they haven't been able to restore.

However, they have taught her to “see” her world in so many different ways. “With the right rehabilitation, a blind person can be extremely productive,” explained Umang Mathur, executive director of the hospital. Mathur has a soft spot for Afghanistan—he did the end part of his schooling (class nine and ten) there. That was in the 1980s, when Afghanistan, under Russian occupation, was a different world—a place where women sported haircuts and where cabarets were happening.

Khatera resumed her story. “I was plunged into the world of darkness, but there was more trouble awaiting,” she said. Her story was being told and retold in Kabul, and this brought her on the Taliban's radar again. Amid all the bleakness, however, there was one more development. Doctors discovered she was pregnant. “I wanted to kill myself so many times since the attack,” she said. “But when I came to know I was going to have a child, I got fresh hope.”

Hope has been a shifty companion for Khatera. It has kept her going during the worst times, but it has also crashed the world around her as many times. Hope then took the form of an American charity worker—Stephanie K. Hanson—who came to know of her. Through charitable foundations Orbis and Seva, which work for eyesight restoration and rehabilitation of the blind, she reached out to Dr Shroff's hospital in India. “With the Taliban focusing on my case, even the government recommended we should go to India for treatment and safety,” said Khatera. Thus, Khatera came to India in December 2020, in the thick of lockdowns, leaving her home, perhaps, forever.

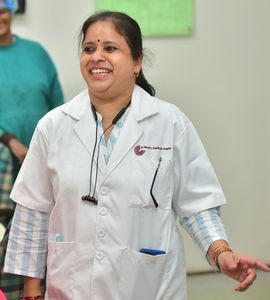

India, for many Afghans, is a land of dreams. It is the solution to their problems. It brims over with possibilities. Khatera came over, clinging on to a hope that the miracle of vision would happen in India. “As of today, we can only do corneal transplants to restore vision. In her case, both the eyes had been mutilated,” explained Dr Sima Das, head of the hospital's oculoplasty and ocular oncology services. In the months before she was shifted to Delhi, the local doctors had anyway removed all the eye tissue. Mathur said that the practice these days was to retain as much of the original tissue, because, sometimes, despite the worst trauma, miracles happened. It could only be a perception of light and dark, but for a patient, even that small perception is a huge empowerment. “The Israeli doctors always recommend saving original tissue,” he explained, but added that ground realities are often very different, and doctors have to take on-the-spot decisions. In Khatera's case, the mutilation was so bad that she even required reconstructive surgery on the eye sockets.

The months that followed were a series of surgeries and recoveries as doctors rebuilt her face. She even had hearing loss in one ear because of the injuries, which has been improved vastly.

Khatera recalled the day when her last hope shattered. The technicians were taking her measurements for artificial eyes. “I knew then that this is my reality.” Khatera's new eyes may be sightless, but they are beautiful works of art, painstakingly hand-painted to replicate what her actual eyes must once have been like. She wears them proudly, they give her confidence in her looks. She “sees” things in different ways, however.

Sonia Srivastava, assistant manager, low vision services, was the messiah who brought a new light to Khatera's life, guiding her through a rehabilitation process that helps her use hands, ears and nose as her new visual aids. The process is slow, often frustrating, but the results are game-changers. “I used to be so scared to be alone,” recalled Khatera. “I would not allow my husband to leave the room. I could not even turn on an electric switch. I used to be scared I would get an electric shock.”

Nabi has loyally stood by her side, taking on every setback with a brave front, and rejoicing in every small progress. Blessed with a daughter last year, he has two demanding women to take care of. “He is also learning a lot,” said Khatera with a warm smile. “Initially, when he would go to the kitchen, he would pester me about how much salt to put, how long to stir a dish and so many other annoying questions. You should taste his cooking now. He makes such delicious chicken.” Nabi smiled shyly at the compliment.

Theirs was a love match. Romance blooms even in the most forbidden environments. Khatera's father was a tailor; she did some sewing, too. She would often go to the market to purchase new material. Soon, the shopkeeper was as much an attraction as the latest bolts of textile, mostly imported from India. “I remember giving him my phone number, so that he could alert me when something new arrived,” said Khatera. Numbers exchanged, the romance bloomed further, till the couple got married four years ago. He has an earlier wife, and several children, all of whom have been left behind as they made their journey to India. “We always thought we would go back, or the family would come to meet,” said Nabi. But first there was Covid-19, then the Taliban takeover in Afghanistan. A reunion seems impossible in the foreseeable future, at least.

The last two years have been trying on their relationship, but Khatera said it helped her “see” people through. “My husband did not give up hope,” she said. “My mother-in-law would nag him constantly to leave me—I was useless and blind. He did not give up on me.” Nabi tugged at his hair. “See all these whites, the last two years have brought them on. The day Khatera was attacked was the worst day of my life,” he said, an involuntary shiver passing over him. He has battled her suicidal thoughts, her struggles with re-learning every little thing, the endless visits to the hospital—it can be intimidating for the well-trained caregiver, let alone someone who has no experience and is himself battling loss at various fronts. But the day Khatera demanded he get a “big speaker” for her to listen to music, he knew that the darkest hour was past. “Such a big speaker she wants,” he said, spreading his hands theatrically. “She always wants loud music.”

Khatera was born when her family lived as refugees in Pakistan, so she speaks and understands Hindi. Even on return to Ghazni, she spoke in Hindi and Urdu with her siblings, watched Bollywood films and listened to Hindi songs.

She is back to humming songs as she manages the few chores she has learnt at home. I ask her to sing. She is shy. But we know there is music bubbling within her. Her husband urges her on with some suggestions. She has a choice of songs from Hindi and Pashto now, and she deliberates, before settling on a Hindi number. It is about loyalty and fidelity. As she began singing, her toddler daughter left the sliced cake she was eating, and listened to her mother in rapt attention. Nabi wore an indulgent look.

There is a new spring in Khatera's life. Recently, she had started attending classes at the National Association for the Blind (NAB) centre in the city, thanks to Srivastava's interventions. “I was so hesitant initially,” she confessed. “I thought, ‘Others will see me spill food, or drop something, it will be so embarrassing’. Then I realised they, too, were sightless. They are also learning, like me.” Khatera has learnt to cook again. She can boil milk and make tea and instant noodles. “I spread my hands over the pot like this,” she says, gesturing with her hands over an imaginary pot. “The temperature changes tell me how far the boiling is progressing.” However, Nabi is lord of the kitchen. “Someone has to take care of Bahar, too,” they said.

Khatera is happy she can do that part. “I can massage, bathe and change her clothes, too,” she said. “I like going with my husband to the market to buy new clothes for her.”

NAB is opening up a whole new world of possibilities for her. Her impoverished living in Ghazni did not give her access to a smartphone, let alone a computer. At the centre here, she is learning to use a computer through voice commands. Srivastava is also teaching her to operate a smartphone with the help of voice commands. Once she is proficient, she will be equipped with a special set of spectacles. These spectacles will have cameras fitted on to them, and will be synced with the phone. They will be a navigation aid, conveying what is before her through voice messages. But the most interesting feature of these spectacles is that they will be able to do a face scan of the person before her. If that person's details match with the entries on her phone, the spectacles will recognise the person, and tell her who is approaching.

Khatera always wanted to see India. “When I got my police job, I had told myself I will save for a trip to India,” she said. “I didn’t know I would be coming here like this. But I am glad I am in India. This is a wonderful place, the people are so good, and they work different miracles here.”

The path ahead is not easy. She still has terrible headaches. There are more surgeries left to repair the damage around the eye orbits and she has only just started down the road of rehabilitation. At some point, Nabi has to think of getting some employment, too. They have got refugee cards, so at least they can stay here without worry. But as Bahar grows up, there will be newer cares to deal with.

Khatera, though, has regained her zest for living, and for taking up challenges, with her love at her side. “Zindagi abhi achchi lagne lagi hai (life is looking good again),” she said.