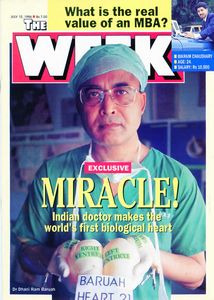

The first recorded xenotransplant in India was performed in January 1997. Dr Dhani Ram Baruah, a cardiothoracic surgeon from Assam, transplanted a pig's heart and lungs into Purna Saikia, a 32-year-old farmer with ventricular septal defect (hole in the heart). The transplant that took 15 hours was carried out at Baruah’s clinic in Sonapur, a small town on the outskirts of Guwahati. Baruah, a fellow of the Royal College of Surgeons, London, performed the procedure along with Dr Jonathan Ho Kei-Shing, a surgeon from Hong Kong.

Saikia had failed to respond to conventional surgery and the xenotransplant was performed as a last resort, with consent from the patient and his family. The transplant went awry. A week after the surgery, Saikia died of multiple infections and hyperacute rejection. “Certain genes and proteins in the tissues of an animal are recognised by the human immune system and this leads to hyperacute rejection,”said Dr Sonal Asthana, lead consultant, hepato-pancreato-biliary and liver transplant surgery, Aster CMI Hospital, Bengaluru. “It is the reason for death in most cases of xenotransplantation. Initial strategies to deal with hyperacute rejection involved profoundly suppressing the host immune system, which left the patient vulnerable to infections.”

Both Baruah and Kei-Shing were arrested under the Transplantation of Human Organs Act, 1994, and imprisoned for 40 days. During the trial, Baruah argued that the act did not cover transplantation of organs taken from other species. Baruah, who is now 72, had a stroke in 2016 that left him unable to speak. People close to him said he was not greatly moved by the Maryland surgeon’s feat.

If Baruah were to perform a xenotransplant now, the chances of survival of the patient would be much higher thanks to the evolution of technology. “Gene editing technologies have made it possible to remove the genes that cause interspecies hyperacute rejection, and insert genes that improve human compatibility,”said Asthana. “Also, CRISPR-Cas9 genome editing [employed to modify the pig heart used in Maryland] has made it easier to create animal organs that are less likely to be attacked by human immune systems.”

As a transplant surgeon, Asthana looks at Baruah’s work objectively. He feels it is important for us to draw lessons from the opprobrium that Baruah had to endure. “To go beyond, India has to create the research and innovation mindset that allows physicians to test new ideas that can save untold numbers of lives,”he said. “Without innovation, there is no progress.”