Mt Kilimanjaro is the largest free-standing mountain on the continent of Africa, standing at an impressive 19,200 feet. It is a dormant volcano and I have been scheming to climb it for a while now. I finally decided on it this February as I felt the pandemic was subsiding. I told my family about it at dinner, and was surprised when my older son, Rohan, 21, asked if he could tag along.

He was never much of the athletic or outdoor type. He did play tennis for his school team, but after he went to college to pursue mechanical engineering, that dropped off, too. With Covid-19 hitting, the last year was pretty much spent at home with limited physical activity and a hefty dose of laziness. “Sure,” I said. But it was going to require a lot of training and sacrifices, not to mention taking three weeks off in the middle of the academic year, which he would have to make up. In addition, this could not be the reason for a fall in grades. He agreed, but I still thought that he had bitten off more than he could chew. He had never been above 8,000ft in his life, and that was during downhill skiing, which does not require much exertion at that altitude.

How do you train for a mountain with that altitude living at sea level? The short answer is you don’t. There really is nothing that would mimic those conditions. Altitude sickness is a funny thing. It hits when you least expect it, and has nothing to do with age or previous fitness. Sure you could try an altitude gym, but there were none near us. We had a bridge that was about 50ft high. I suggested he wear a backpack weighing at least 30 pounds and keep going up and down the bridge, along with weight training. We would do a few practice climbs in the Rocky Mountains to test the strategy. We had six months to prepare.

After three months of training, which I assumed he had done, we made a plan to climb Pikes Peak in Colorado, at an elevation of 14,100ft, by the end of May. It would be his first ‘fourteener’ as they are called. I thought we should do the climb over two days, but he insisted that we do it in one day. The plan was straightforward—we fly into Colorado Springs, which would be our base camp, acclimatise for a day to get our bodies adjusted to the low atmospheric pressure and climb the next day. That would be 7,600ft of climbing in one day, and take the train back down. As luck would have it, there was a storm moving in the day we flew in. We decided to climb without the day of acclimatisation to avoid the storm. There is a small camp halfway called Barr Camp, where you can rest, refill water from a stream (you have to carry your own water purification system) and even spend the night if you have reservations.

We made it to Barr camp without an issue, but after that I saw him struggling. He didn’t complain, but we had slowed to a crawl at 11,000ft and we weren’t going to make the summit in time. I asked if he had a headache, and he said that it was going on for an hour and was pretty bad. I knew this was altitude sickness causing mild swelling of his brain—a condition called cerebral oedema—and we had to descend. He didn’t argue with the call. The route was snowed in, too, but the downside was that we had to hike back all the way down. The whole hike took us 12 hours and we were both barely able to walk back to our jeep.

I thought that would deter him, but he said we should train harder and return. We did so after another two months, by the end of July. I used to get a text message at 3am most mornings, saying, “Let’s train.” He was away in college and going to the gym before his classes. This time we got smarter. We decided to spend a night at Barr camp at 10,500ft and attempt the summit the next day. He again struggled at 12,000ft. Pikes Peak has these notorious switchbacks—the zigzag route that seems to go on forever—but this time we kept pushing, with ibuprofen and steroids for his headache and finally reached the summit. It was euphoric for him—which consisted of a wry smile and a few animated words.

In October, as we were flying to Doha en route to Kilimanjaro, we were seated separately. I went to check in on him and he was sleeping. The flight attendant told me he was shy and polite. We both envied his ability to sleep. We had learnt a lot about each other on the mountains. We were completely different people. He had grown into a young man who had few wants and minimal needs to be happy. The material world that I had strived for meant nothing to him. Socially, too, we were poles apart—he did not have a Facebook or Instagram account. The huge hulk of a mountain was waiting for us, but it suddenly seemed immaterial on whether we would summit. In my mind, we had already scaled a higher mountain.

A shot at Kilimanjaro

The alarm went off at 11pm on October 9, but I was already awake, thinking about everything and anything that could go wrong on summit night. Beside me, my son was fast asleep—boy, could he sleep! I woke him up and we got dressed in the cold tent with our flashlights. A hot cup of tea and biscuits awaited us at the food tent. While hiking, food is a lot of carbohydrate and protein-rich bars during the day, including rice, pasta, chicken and mutton—all prepared at camp by the local Tanzania support team. We had carried sleeping bags, rated to -30°F, sleeping pads and plenty of warm clothes. The key is to have multiple layers—a base layer, a middle layer and outer waterproof layer, if needed. On summit night, we needed all layers, gloves, two layers of woollen socks and hand warmers. We went through one last gear check, and went through the route plan again. At 12am, we went out into the cold and dark night making our bid to summit.

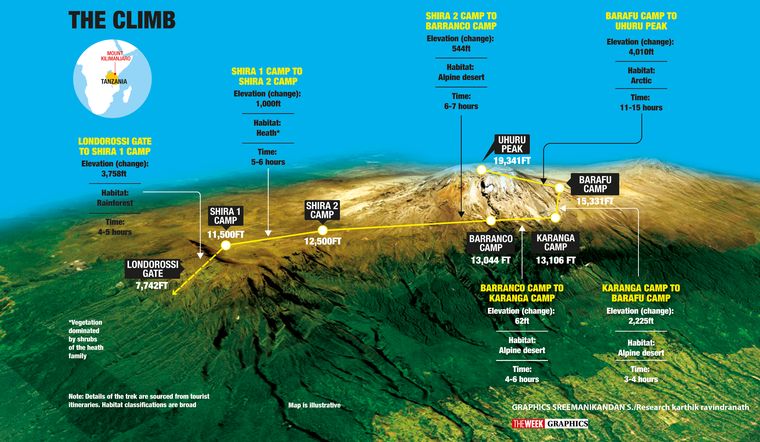

Earlier that afternoon, we had rolled into base camp at 15,200ft. The last four days had been hiking six to eight hours a day as we made our way to the mountain through the modified Shira route and acclimatised to the altitude. The rule of climbing is to trek higher each day and camp lower, getting the body to adjust to the higher altitude. Contrary to popular perception, the amount of oxygen is unchanged—it is 21 per cent. But the lower atmosphere pressure causes the oxygen molecules to disperse, making for fewer molecules during each breath. The five days of hiking, sleeping out in tents, the poor toilet facilities, weather and altitude were beginning to take a toll. Luckily, despite the close quarters, and the constant fatigue, everyone was holding up reasonably well. We lost one of our colleagues, who recognised he was not adapting to the altitude and made the call to head back down to lower camp.

It was pitch black with only the boot of the person in front visible to us through our headlamps. We had 18 doctors in our group, most of them serious and experienced hikers. There were two father-son combinations. Luke was a cute spunky 13-year-old with a Michigan baseball cap, dark glasses and a naughty smile. He was there with his father, an orthopaedic surgeon. Luke would lead the pack. On two occasions, he had issues with altitude sickness, but bounced back with medication. He was in the lead, behind the guide, this time as well. His backpack was being carried by his father to lessen the load on the final assault. Rohan was right behind Luke’s dad.

The two keys to climbing are to avoid sweating and to avoid breathing too hard which would need you to stop more frequently. You need to stay on the cooler side, as sweat dampens your base layer. When you stop, you lose heat 25 times faster, as it takes a lot of body heat to warm the wet layer. When we got out of base camp, we were immediately into a steep ridge, causing me to overheat and jack up my heart rate. I thought the pace was too fast. I hung out at the back, shedding layers to get back to pace and after a while got my rhythm back. The group in front pressed on, and with two novice climbers in front, I thought we were headed for trouble.

As we climbed higher, I could see Luke tiring. I asked him how he felt and he said he was trying to keep pace with the guide and was getting exhausted. Luke and Rohan were doing what kids do—keep up with the pace, taking it on as a challenge, rather than listen to their bodies and create their own pace. I got into a bit of back and forth with the guide. I told him he was going too fast and he politely told me he was the expert on the mountain and knew what he was doing. I politely reminded him I was the expert on the human body. And the matter was settled—we slowed down. We continued on the near vertical trudge, with quick stops to keep chewing on our bars for nutrition.

At around 18,000ft, the group was in varying stages of disarray. The portable water that we carried on our backs was frozen. We were briefed on this and switched to drinking from Nalgene bottles. The sun was just beginning to come up and I took a minute to take in the beauty of the mountain. I was still feeling reasonably good and the altitude was not affecting me as much as I thought it would. The lead guide identified four of us to go ahead. Three of us were experienced hikers, and we let inexperienced Rohan lead us. He was surprisingly getting stronger the higher we went. The last 1,000ft seemed to take forever, and every time we crested a ridge, thinking we had reached the summit, we would realise that it was a false summit. The true summit seemed to be just out of reach, tantalisingly close, almost mocking us. We climbed false summit after false summit till the true summit was in sight. And, at 7.30am on October 10, after a 7.5-hour-long climb, the inexperienced non-hiker, with no previous high-altitude exposure, led us to the summit.

There is nothing magical on a summit. It is just a piece of rock. The magic lies in the journey, the perseverance and the pain that you put yourself through. The mountain does not discriminate—it punishes everyone—and in the process always changes you. It may be subtle, but you are a changed person. The harshness makes a more kinder and gentler person out of you, as you realise how insignificant you are compared to nature. The kids got to learn this at an early age. The four of us were alone at the summit. It was serene, with breathtaking views. We sat down for a bit and just took in the moment. We were at the highest point on the continent and there was nowhere else to go, literally and metaphorically. Doing this climb with my son and spending time together and discovering each other has made this my most memorable climb.

As far as physical endurance goes, I still think the Ironman endurance race is the toughest. This would count as a close second. I keep learning on how much I can push my body. I honestly feel more comfortable now, than when I was younger, about the extent to which I can ask my body to push without breaking down. The experience and the pace really helps. I know the body well as a doctor and it is interesting to see how far I can take it. This gives me a better perspective on how to advise my patients, my friends and family as I have experienced the situations I advise them about. It is different from pure academic knowledge. I think it helps me to be a better doctor and, more important, a better person. It also helps me focus on the more important things in life, like time and relationships. The time spent with my son was priceless.

We took the obligatory pictures at the summit and commenced our descent. We had a long road ahead of us— we had to descend 14,000ft over the next day. We met the rest of the group, led by a determined Luke. Everyone made summit. The descent was uneventful, except for one part where I lost my footing and fell on to a rock. “You okay, Dad?” I heard a voice call and looked up to see Rohan with a quizzical half smile. I had been asking him that same question all week, so I guess it was payback. “Yes,” I replied sheepishly, as I got back on my feet. Luckily, nothing was hurt except for my self-esteem.

On the first day as we were registering at the main gate, I saw a man sitting by himself. I introduced myself and my son as I thought he looked lonely. His name was Mick and he was from Amsterdam. Turned out, he had split from his wife and decided to climb Kilimanjaro on a whim. He was all lean muscle and in good shape, so this wasn’t his first rodeo. One of the things about the mountains is you meet people—strong people—and form relationships. For some reason we pour our hearts out to each other—complete strangers. Sometimes you only know first names, phone numbers are not exchanged and most of the time you never see each other again (if you are lucky on occasion you do), but you draw from each other at that point of time. We made friends with the local people. Our lead guide was a gentleman by the name of Festo. He spoke good English. We talked about everything, including our daily lives, ambitions, family and altitude climbing. The local people, well versed with the mountains, gave us a historical context as well as guided us every step of the way while climbing. It would be a very difficult, if not impossible, proposition to attempt the climb without their experience.

I saw Mick coming down as I was getting into base camp after an hour and a half descent. “Amsterdam,” I shouted across the ridge. He looked up and smiled. “Dinesh,” he shouted back, raising his arm. “I saw Rohan up ahead, and he is looking strong.” “How was the summit?” I asked. He thought for a bit, and said, “I have never felt more physically broken and yet so mentally whole.” I was not quite so physically broken, but I did feel mentally whole.

—The writer is clinical assistant professor of medicine, Florida State University, and director, interventional and structural cardiology, AdventHealth, Daytona Beach, US.