The world's hope now resides in a vial of vaccine.

And, Abraham Kovelil Jacob thinks he was destined to be a vaccine volunteer. Jacob, who works for the National Health Service in the UK, is part of the AstraZeneca-Oxford University trials for a Covid-19 vaccine. “One of our patients died because of Covid-19,” he says. “She would often scream in pain. One day, she grasped my colleague’s hands and begged her to kill her. Her words kept ringing in my ears. A few hours later, I saw a mail on the University of Oxford’s Covid-19 vaccine trials.” The 47-year-old is probably one of the first Indians to receive the much-awaited vaccine.

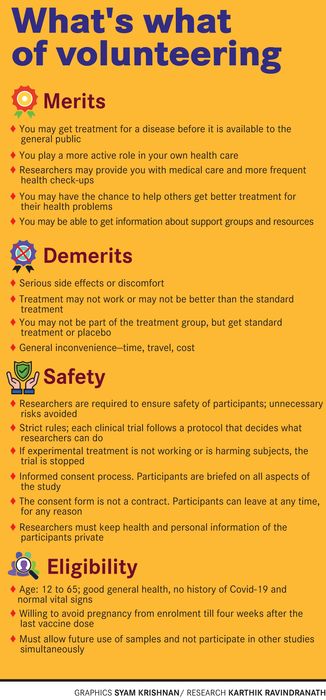

Vaccine volunteering involves walking the untrodden path. Human trials are crucial to vaccine development. The trials, conducted in three distinct phases, allow vaccine researchers to assess the safety and efficacy of the vaccine before making it available to the general population.

Phase 3 trials for ChAdOx1 nCoV-19, popularly known as the Oxford vaccine, are currently underway, and 18,000 people have been vaccinated. The trials have shown that the vaccine induces a strong immune response. It produces antibodies and T cells that offer protection against Covid-19.

But what does it take to be a volunteer? A pre-assessment is done to check one's suitability. “There was a basic health questionnaire, followed by observations like pulse, blood pressure, respiratory rate, oxygen saturation and blood tests,” says Dr Yamuna Madhu, a 49-year-old critical care specialist from Newcastle upon Tyne in England.

Being a vaccine volunteer means a long-term commitment. The Oxford trials may continue for 6 to 12 months. Blood tests are to be done not just before the vaccination but also on Day 28, Day 90 and Day 180.

Peterborough resident Dr Praveen Kumar, consultant psychiatrist at Cambridge University Hospitals, drives 72km each way to get his blood tests done at Addenbrookes Hospitals in Cambridge. Trial participants also have to send out their nose and throat swab samples for testing once a week for about nine months. “I collect my swab, put it in a pack and post it every week,” says Kumar, who hails from Tirupati. “So far all the swab results have come back negative.”

The participants in the trials do not know whether they are receiving the experimental Covid-19 vaccine or MenACWY, a vaccine used to prevent meningitis. The trials use a double blind design—neither the researchers nor the participants know who is receiving which treatment. Volunteers who have been given the meningitis vaccine will be given the Covid-19 vaccine for free later.

Kumar, 48, says that he thought he would experience some pain or redness at the site of the injection, as is usual with other vaccines. “I get a flu shot every year. It can be painful at times and sometimes I experience symptoms of flu,” he says. “But with this vaccine, I haven’t experienced any side-effects at all so far.” He had his initial dose two months ago, followed by a booster shot in October. “Introduction of booster dose suggests that the vaccine makers are taking every precaution to make sure they are able to come out with a very efficient vaccine,” says Kumar.

But not every participant in the vaccine trial has had such a smooth journey. Victoria Bolderson, a community psychiatric nurse and lead electroconvulsive therapy nurse with The Cavell Centre, Peterborough, “felt pretty terrible” the night after she received the vaccine. She experienced tiredness and flu-like symptoms.

Following reports of a serious adverse reaction, the trial was paused and Kumar's appointment for the booster dose was postponed. Kumar's mother did not want him to go ahead with the trial. “I convinced and reassured her that one adverse event in 18,000 doses of vaccine suggests a fantastic safety profile of the product,” says Kumar.

How good is the immune response produced by the vaccine? “They don’t individually report the immune response,” says a 45-year-old participant in the Phase 2 trials. “They will do it only after the end of the vaccine trial.”

Sharing the results of the antibody test at this point may cause bias, which will, in turn, affect the study. For instance, a participant who develops antibodies after the vaccination may guess that he was given the ChAdOx1 nCoV- 19 and may have a false sense of reassurance, leading to a less careful attitude.

Madhu joined the vaccine trials driven by a sense of duty. “Participating in the trial was something I could do to help with developing a vaccine,” she says. “At that time, north of England, where I live and work, was not as badly affected as the rest of the country and some other parts of the world. However, when I read about what was happening in the rest of the world, I felt I had to do more than what I was doing [as a doctor].”

Another volunteer who took part in the Phase 2 trials says he is motivated by compassion. “I am doing my bit to bring the pandemic to an end. On a personal level, I have an elderly mother and relatives with co-morbidities such as diabetes and hypertension. There are also several frontline workers in our family—11 of us are doctors. I felt that it is important to get involved in these trials as it helps develop the vaccine as quickly as possible.”

There are many myths surrounding clinical trials. “The common man will have all sorts of anxieties taking part in a trial,” says Kumar, who has been living in the UK for 15 years. “People don’t want to be seen as guinea pigs. There are lots of cultural issues as well. People have their own beliefs. I am from India and participating in clinical trials is not something that many of us are used to. We are gradually getting exposed to the culture of organ and blood donation, but sadly clinical trials still remain something of a taboo for most Indians.”

One of the biggest challenges faced by the Oxford vaccine researchers is the under-representation of black, Asian and minority ethnic (BAME) groups in the trials, says Kumar, who is one of the first ethnic minority doctors to join the trial. UK’s BAME community has been hit hard by Covid-19. A study conducted by Public Health England, an executive agency of the Department of Health and Social Care, shows that death rates were significantly higher among people of black and Asian ethnic groups in comparison to their white counterparts. “Among the first 100 medical professionals who died in the UK, a significant majority of them were people of ethnic minorities,” says Kumar. “The BAME workforce is usually concentrated in bigger cities like London, Birmingham and Manchester, where the infection rates are high. Ethnic minorities have some sort of hesitation to say no to work even in adverse times. The higher incidence of Covid-19 seen in BAME groups coupled with their low participation in clinical trials is a great cause for concern.”

Ramesh Subbiah, an inclusion manager at Cambridgeshire and Peterborough NHS Foundation Trust, attributes the low participation of ethnic and racial minorities in clinical trials to psychological factors. “It is mainly owing to worries people have about their health condition,” says Subbiah. “Those from the BAME community have been disproportionately affected by Covid-19. Creating psychological safety for all is an important part of recruiting for any vaccine trial, especially for Covid-19 vaccine trial.”

Subbiah, 41, had registered to take part in the trials, but could not as he lost a close friend and a colleague during that time. “A few colleagues also got infected with Covid-19 and ended up in hospital with complications,” he says. “I was busy focusing on supporting my colleagues and their family. But I will be taking part in upcoming trial opportunities.”

As Kate Bingham, who chairs the UK government's vaccine taskforce, recently said, “Researchers need data from different communities and different people to improve understanding of the vaccines. The only way to get this is through large clinical trials.” Kumar considers it a win-win situation for minorities to take part in trials. “There is a lot for us in return,” he says. “If we contribute to a vaccine trial and we prove that it is efficacious in a wide range of ethnicities, I think that will limit the damage the virus causes to us.”

Madhu, too, encourages people to participate in the Oxford vaccine trial. “It is a very well conducted and well-informed scientific study, maintaining high ethical standards,” she says. “When there were suspicions of major side-effects, the study was suspended. The incidents were reviewed by an independent committee, and the study was resumed when it was found the suspected side-effects were not related to the vaccine. These participants were regularly informed. This sharing of information has increased my confidence in the safety and clarity of the trial.”

No matter how safe the trials are, it would have made some family members anxious. Bolderson did not tell her parents, sister and mother-in-law for fear of worrying them. But her husband was proud of her when she first told him about it. “I think the various vaccines are our best hope of getting all our lives back to normal, and Victoria helping with that is great,” says Karl. “I was a little nervous about the trial—how would Victoria respond to the injection, would it make her ill? But with this being a Phase 3 trial, many people had already had the vaccine without any major issues, and I trust the scientists and doctors involved to look after everyone’s health.”

Jacob's wife, Susan, also responded positively to his volunteering. “As someone who takes care of terminally ill patients, she knows how grave the situation is and was happy that I am doing my bit for society,” says Jacob, who lives in Peterborough. “My children, however, are concerned. They keep asking me, 'What if things go out of hand?' I believe in science and God. Moreover, I feel I am morally bound to serve humanity.”

Madhu's son, who will turn 19, was curious to know whether she was given a control vaccine or actual vaccine and if she would get symptoms. “I do not think he was much worried about the possible risk involved as he has great confidence in science,” she says. “At the same time there was a bit of apprehension and a lot of uncertainties, which we managed through regular conversations. At the end what remains is a sense of satisfaction.”

Conversation has helped not just calm nerves but also clear misconceptions. “My children asked me if I made myself a guinea pig for the experiment, but they were more appreciative after I explained things in detail,” says Kumar, who wants to set an example for his children. “The younger one, Vishal, 13, felt it was cool to be part of such a huge thing. Nikhil, 18, asked questions about safety and complications. But neither of them showed any great concern. I could, however, sense the worry in Sailaja, my wife, a dentist who has her own practice.” That has not deterred Kumar, who thinks that it is everyone's duty to donate organs and contribute to scientific studies whenever one can.

As one waits for the trials to end, the question on everyone's mind is: When will we have a vaccine? Initial information coming out of the trial groups suggests that health care workers and the elderly will be vaccinated by around early next year, hopefully by January.

The countdown has begun.