Dhairya Soni, five, looks like any other boy his age. He runs around, plays and cycles with friends and dances to Bollywood music. But, unlike others, being active and in control does not come naturally to him. It takes 13 units of insulin every day and a strict diet plan—no ice cream or chocolates—to keep him happy and energetic. This is because the Mumbai boy has type 1 diabetes—an autoimmune condition in which the beta cells in the pancreas lose the ability to produce insulin, the hormone that keeps the body's blood-sugar level in check. Dhairya's mother monitors his sugar level several times a day and makes sure he plays for at least two hours so that the excess sugar in his body gets used up. She also takes him for regular eye checkups and blood tests.

It all began two years ago when a toilet-trained Dhairya began wetting his bed. “We were stunned to see how his body was changing all of a sudden,” says his grandfather Girish Soni. “Despite feeling excessively hungry and eating more than usual, he would be fatigued and listless all the time and was also losing weight rapidly.” Unexplained weight loss, frequent urination and excessive hunger and thirst are the first symptoms of type 1 diabetes in children, which often strikes them after the age of three.

The excess sugar that builds up in a child's bloodstream pulls fluid from the tissues and makes him lose water more than usual. In the absence of insulin, which can help in the conversion of sugar into energy, the child's muscles and organs lack energy, thereby triggering intense hunger. “Type 1 diabetes is one of the most common paediatric endocrine illnesses,” says Dr Prasanna Kumar from Bengaluru, whose research on type 1 diabetes got published in the Indian Journal of Endocrinology and Metabolism. “It affects nearly five lakh children. Of these, over half live in developing nations, with India being home to an estimated 97,700.”

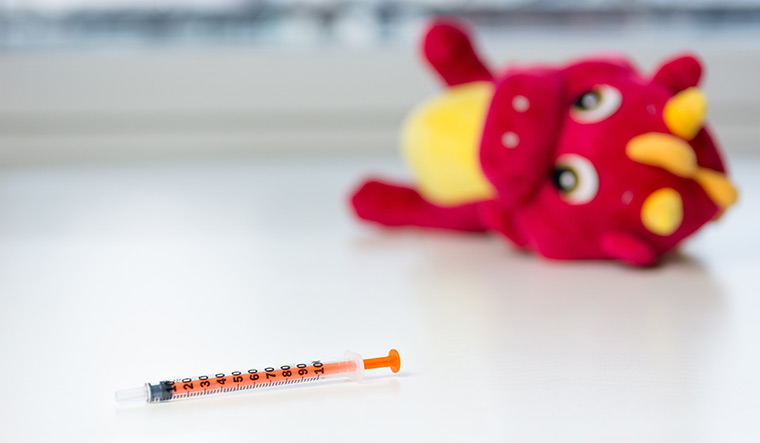

These children must be on a lifetime of insulin supply to manage the lack of insulin in their bodies and to prevent hyperglycaemia (excess glucose in the bloodstream), hypoglycaemia (deficiency of glucose in the bloodstream), ketoacidosis (a buildup of acids in the blood) and other complications.

“Unfortunately, science has not been able to explain the cause of this autoimmune condition,” says Dr Pradeep Gadge, a diabetologist in Mumbai. “It has nothing to do with genetics, family history or even an improper lifestyle. The body itself shuts down the pancreas from making insulin. It is the sheer misfortune of those children who fall prey to this beast.”

Priyanka, a state-level topper who is studying to be an electronics engineer in Bengaluru, was the first in her family to be diagnosed as diabetic, at the age of seven. “We were shocked,” says her father Ravindra Kumar. “Nobody in our family suffered from diabetes at the time. Initially, we blamed ourselves for it but then were told that there was no real explanation for it and no external factor had caused it. And to know that there was nothing we could do about it but to keep her on insulin for her entire life was extremely disheartening.”

The parents made a strict daily schedule for timely injections and a low-carb, high-protein diet with loads of fruits and vegetables—a habit that has remained with her even today. “It has been 11 years since I was diagnosed with type 1 diabetes, but I really never felt inconvenienced in any way,” says Priyanka. “This is mainly because the dietary discipline that my parents have put me through is so ingrained in me that I never feel the need to cheat. As per plan, I must never miss my injections, limit desserts to once in a fortnight and exercise every day.”

According to experts, diabetes has a huge psychosocial impact on children, especially as they face discrimination for carrying the insulin kit and injecting themselves at regular intervals. “I have had instances when children have approached me with an earnest request for shifting their insulin doses to after-school timings as they felt shy and embarrassed to take insulin in the presence of their friends and classmates,” says Gadge. “In such cases, we mostly write a letter to the school requesting them for full cooperation. I do not advise the child to keep her diabetes a secret because it can cause problems when her body experiences dizziness and fatigue due to sudden lowering of blood sugar. Diabetes self-management is a continuous job.”

Parents are also educating children on disease management using storybooks, videos and counselling. “We have also been to camps where doctors counsel parents and children on multiple aspects of living with type 1 diabetes, including self-injection techniques, awareness about hypoglycaemia, managing simple hypoglycaemia, and knowing the essentials while travelling, at school and during holidays,” says Mehul Thakkar, father of Niket, 12, who has type 1 diabetes.

While type 1 is the more common form of diabetes among children, doctors have lately observed an increase in type 2 diabetes in children and teens. “Until now, we all believed that childhood diabetes invariably meant type 1 diabetes,” says Dr Phulrenu Chauhan, endocrinologist at P.D. Hinduja Hospital in Mumbai. “That is how it was until a few years ago. Then we noticed that a lot of children were coming to us with type 2 diabetes, which is essentially an adult form of diabetes generally seen after the age of 40. One primary reason for this is decreased physical activity, increased screen time, uncontrolled consumption of junk food and obesity.”

Agrees Dr David Chandy, consultant in endocrinology at Sir H.N. Reliance Foundation Hospital, Mumbai. He says that it is primarily a disproportionate increase in the belly fat among children aged eight to 10 that renders the insulin ineffective and exposes them to type 2 diabetes. “About 10 years ago, there must have been hardly one patient suffering from type 2 diabetes below the age of 20 in my clinic,” he says. “But now, I see about five such patients in three months. The darkening of skin behind the neck of children is an early sign of insulin resistance and parents must check for this at regular intervals. It is called acanthosis and literally means a black, velvety carpet. It means that the body's insulin is losing the fight and gradually the child will have diabetes.”

Another aspect that almost all doctors agree on is the need to counsel parents so that they do not experiment with different treatments for their children. Sticking with insulin is the best way, say doctors.

Moreover, the advances in blood-sugar monitoring and insulin delivery have improved the daily management of the condition. In terms of technological advancements for children with type 1 diabetes, the latest is an insulin pump that works very well for a child above the age of seven. Its advantage is that it continuously gives insulin and has a sensor that will stop the process when needed. “But the cost is Rs3 lakh to Rs5 lakh for the device and a monthly expense of about Rs10,000 to Rs15,000,” says Dr Chauhan. “Also, one has to be tech savvy to actually help the child use it.”