It is because everyone looks at your face, not what’s inside,” says Dr Niya, 42, when asked about the multiple facial surgeries that she has undergone in the past four years. “It is what you see every day in the mirror. And, you have to be at peace with what you see.”

Born male, Niya, who prefers I use her first name only, lived as a man for more than 35 years. For the world, she was a man. She wore “unisex T-shirts, jackets and pants”, spoke like a man, and behaved like one, too. Inside of her though, Niya, since she was seven years old, knew she was a woman.

About five years ago, things began to change. In 2014, Niya, who works as an anaesthetist at a government hospital in Maharashtra’s Thane district, finally began to realise her dream. That year, she went for a gender reassignment surgery (GRS), and started to live as a woman.

Much before she opted for GRS, the more common surgery associated with transsexuals, Niya had wanted to get a different procedure done. She had been poring over medical literature on the subject, and even began contacting some of India’s top plastic surgeons to ask whether they could perform those procedures that, she believed, would allow her to be the woman she had always wanted to be.

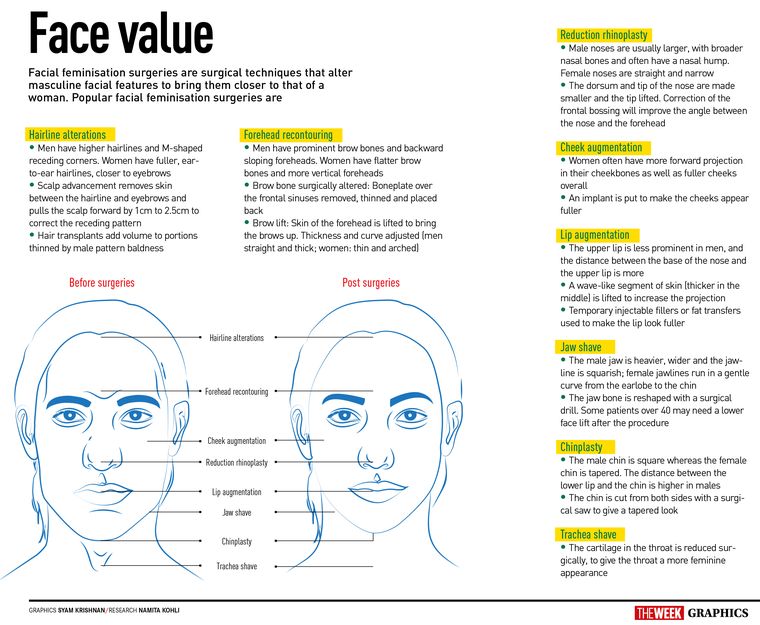

These procedures, together known as facial feminisation surgeries (FFS), include surgical techniques that alter masculine facial features to bring them closer to that of a woman. The ‘feminising’ techniques involve ‘shaving’ facial bones and soft tissues to smoothen, soften, structure and shape prominent facial features such as the forehead, jaw and chin. Some of these procedures include forehead reconstruction or contouring, brow lift, rhinoplasty, cheek implants, lip lift, lip augmentation, chin and jaw recontouring and face lift.

Globally, FFS procedures are fairly popular among transwomen, particularly in countries such as the US, the UK and Europe. In India though, given the prohibitive costs of these surgeries (upwards of Rs5 lakh, depending on the number of procedures desired) and the limited expertise available, the number of trans patients who are getting them currently is not huge. But the demand is steadily rising, say surgeons. Even non-trans patients ask for these procedures to enhance their femininity, says Dr Debraj Shome, a Mumbai-based facial plastic surgeon.

The reconstruction of facial features to feminise them is surgically complex. It involves the nuances of facial gender differentiation, and calls for distinct professional expertise. “It is not just about changing the nose to make it more beautiful, which is a common procedure that any plastic surgeon can do. Here, the idea is to make a certain part, such as the nose, look more feminine. Besides, each face is different, and we work with individual patients to understand what changes will work for them,” says Dr Narendra Kaushik of Olmec transgender clinic in Delhi. Chennai-based oral and maxillofacial surgeon Dr S.M. Balaji says he prefers “long interviews” with his trans patients to design the “new look”. “These surgeries require more than clinical and surgical acumen,” he says. “Understanding their mental makeup is also essential, as is managing their expectations, which can be really high at times. Besides achieving symmetry on the face, the management of expectations can be challenging.”

Depending on the face—and the costs involved—decisions on the “look” are made. Is a nose job really required? Or, will just an alteration of the forehead, jaw and chin be enough to pass off as a woman?

For transwomen such as Niya, the transformative power of the surgery— sometimes even more than the genital surgery—lies in their ability to pass off as women post it, and hence gain a higher degree of social acceptance. “You go out in the crowd and people look at you. They don’t know you, but they look at your face for maybe just a couple of seconds. In that time, they assess your gender—man or woman. In that moment, you want to fit in, and not confuse them. Because if they are confused, they will give you a second look. Now, they have marked you as different... abnormal... maybe even a freak,” she says, adjusting a delicate pair of rimless spectacles that sit on her slim nose.

In her own case, Niya has resolved the “confusion”. Behind the rimless spectacles, you notice her doe-shaped eyes framed by high-arch eyebrows that sit on a smooth forehead. Her cheeks plump up when she smiles, and her jawline tapers towards a somewhat rounded chin. Her wheatish complexion is smooth and flawless, and for a stranger, it is hard to tell that this face has been “worked on” extensively. Her face is sans makeup or jewellery, except a pair of diamond studs on the upper portion of her ear.

The “naturally feminine look” has not come easy. When Niya, who says she is possibly the first transwoman in India to get facial feminisation surgery, started researching the subject, she couldn’t find a surgeon who was willing to do it. “At that time, most surgeons in India were scared because it is a new procedure. No one wanted to experiment, and that, too, on a face. Even now, only a handful of surgeons offer these procedures,” she says.

The basis of FFS procedures lies in the surgical sub-speciality of craniofacial and maxillofacial surgery. Experts in this sub-speciality—and India has many—work on the face, jaw, palate and skull, to address a range of problems by reconstructing the missing or damaged skeleton, correcting deformities of the skull, closing the palate and rebuilding facial features.

Niya, a medical professional herself, understood this well, and began contacting surgeons within this sub-speciality. She even managed to convince a surgeon at a reputed private hospital in Mumbai to perform the facial surgery. But on the day of the surgery, as Niya lay on the OT bed, the surgeon freaked out and said, “You will get me into trouble!”. He refused to do the surgery, she recalls.

“FFS is an art. And, when it comes to the face, our fight is in the range of millimetres,” says Kaushik. A difference of a few millimetres, he says, can change a facial feature from male to female, and alter a patient’s facial expression. “The position of each feature is relative. For example, the distance between the base of the nose and the upper lip, the distance between the hairline and the eyebrows, all of these could make a face feminine or masculine,” says Kaushik.

The alterations that surgeons make are based on the science and mathematics of facial gender differentiation, developed in the early 1980s by Dr Douglas Ousterhout, a San Francisco-based cranio-maxillofacial surgeon. Drawing from the discipline of physical anthropology, Ousterhout, also referred to as the father of FFS, developed the theory of the 'female face' as one defined by a smaller, smoother (or convex) and vertical forehead; the comparatively smaller distance between the eyebrows and the hairline; a smaller gap between the base of the nose and the lips; V-shaped jawline and a slim nose.

The core of FFS surgeries is the forehead feminising surgery. For many transwomen, this procedure is enough to achieve a desirable femininity, says Niya. In this procedure, the surgeon reduces the brow bossing [masculine foreheads tend to have a ridge of bone running right across them at about eyebrow level,], removes the irregularities and the protrusions of the male forehead and makes it smoother and vertical, like that of a woman, explains Kaushik.

“The ideal feminine forehead requires an aggressive approach by the surgeon,” says Niya. She describes how surgeons use different ways to smoothen the male brow bossing: Type 1, where the bone is merely shaved; Type 2, where the bone is shaved and filled with bone cement to achieve a smoother look; Type 3, a more aggressive technique of cutting through the anterior wall of the sinus cavity, restructuring the wall and pushing it back to get a flatter effect.

“Think of our sinus cavity like a house with four walls. You want to bring the front wall back, so, the best way is to break it down and set it back,” she says. “In Type 3, the surgeon has to cut through the sinus wall, the bone plate that lies behind the space between the eyes, that space where an Indian woman applies a bindi.”

Here, the surgeon’s skill is important. “If the bone was merely shaved and some bone cement added to create a smoother appearance, the result would be a 'dolphin forehead', a rounder but outward projecting forehead, as opposed to a flatter [feminine] look,” explains Kaushik.

After the forehead and the eyebrow lift, most transwomen tend to opt for the jaw and chin contouring, to complete the softening of the features. The efficacy of the facial procedures takes a few months to show, and sometimes several revisions are required, too. For Niya, it meant another surgery for the forehead, a hair transplant that she got done in April, and two revision surgeries on the jaw and the chin that she is planning to get done. For Niya’s Kolkata-based friend Ankita (name changed), it has taken four forehead surgeries, three nose surgeries, and another three to correct the jaw and the chin. “Now she has a beautiful face,” says Niya.

Not all transwomen want the procedure, Niya clarifies. “Few will have a naturally tapering jawline, and perhaps even a rounder chin, and won’t need surgery. Conversely, even cis-women have certain masculine features, but overall, the impression is that this is the face of a woman,” she says.

Post surgery, how the new face gets read, is a layered process too. Niya recalls that initially it was difficult for her to even step out. “I wasn’t sure how people would respond. It would take me about 15-20 minutes to muster the courage to go out, and face the world,” she says.

In her situation, Niya faced an interesting contradiction. During the transition phase, when she was on hormone therapy and had had her GRS, her face was hairless, she had long hair, but still wore unisex clothing. “Some people would get confused about how to address me—Sir or Ma’am. Because of my male name, they were compelled to address me as Sir, even though they felt that I looked like a woman,” she says. “Now, post my complete transition, they are having trouble switching to Ma’am, which is what they had believed in the first place!”

Beyond social recognition though, Niya, also known as Niyatee among friends, says that the face is important not just in the social context, but also for the self. “It is about aligning your outer self with your inner self. I feel complete now,” says Niya.

All the changes, and the entire journey of Niya’s transition and recognition apart, there is one thing that has remained the same—her family members have accepted her trans status, but still address her by her male name. “It is okay with me. They are used to that name,” she says. “Besides, I think I am beyond gender now. I am at peace with my identity. In the end, that is all that matters.”