On most days, the life of a virologist would make for gripping science fiction. Dr Rima Sahay, a scientist at National Institute of Virology (NIV), Pune, describes how a day in her life, of late, includes navigating multiple layers of security, stepping in and out of “chemical showers”, slipping in and out of Tyvek suits (coveralls that are worn while working with dangerous biochemicals or pathogens) and decoding the structure of a virus and its history within 24 hours.

In Manipal, Dr G. Arunkumar, head, Manipal Centre for Virus Research (MCVR), is busy solving several mysteries. He tries to find out how the deadly Nipah virus struck one family in Kerala and challenged the entire public health infrastructure in the country, even as he investigates the dominant viruses in some 40,000 samples from across the country, identifying them from a list of 80 probables.

In the past few months, some of the country’s leading virologists have moved from biosafety level 1 and 2 laboratories to the extreme biosafety level 4 (BSL-4) facilities, where even the air they breathe is filtered through powered air purifier respirators (PAPR) that are attached to their Tyvek suits. Sahay works at the BSL-4 laboratory at the maximum containment facility in NIV, a high-security zone where access is limited, given the risks involved in working with deadly viruses.

Inside the facility, scientists perform molecular tests for high risk pathogens, conduct various studies on their disease potential and biology, study human immune responses to them and try to develop vaccines and treatment against them. Outside the high-security zone, in adjacent laboratories of level 1, 2 and 3, large machines fed with virus samples spit out data on their structures, family trees and genetic constituents, allowing virus detectives to answer the crucial questions. Is the virus weak or strong? How does it interact with our immune system? Why does it affect some people, and not others? The virus sleuths will also trace the distances that the virus has travelled and predict its future path, in the hope that another outbreak can be contained, and perhaps even prevented.

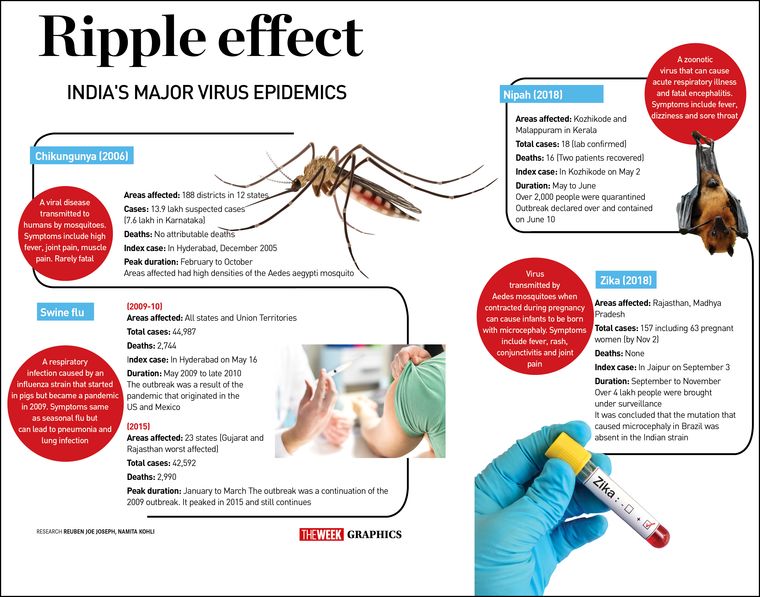

For a virologist, it is all in a day’s work. But, with two major outbreaks in the span of a few months in 2018—the Nipah virus outbreak in Kerala in May and the Zika virus outbreak in Jaipur and Bhopal in October-November—the days have only become longer. Any major viral outbreak such as the deadly Nipah virus means finding answers to several questions, beginning with zeroing in on the exact virus from hundreds of possibilities. “In the case of Nipah, we had information about the unusual cluster of encephalitis and a recent death in the family with similar symptoms from Dr Anoop Kumar, an intensivist [critical care physician] at Kozhikode, Kerala. We knew that this was not going to be easy. Though we did suspect and test for the rare Nipah virus, we also ran tests to rule out common causes of encephalitis such as Herpes Simplex Encephalitis, Japanese encephalitis, rabies, pulmonary leptospirosis and several others,” says Dr Arunkumar, whose laboratory in Manipal was able to identify the virus within 12 hours of receiving the samples.

Viruses are typically confusing foes, and each outbreak will send experts into a tailspin. The microscopic enemy will appear, disappear and even be passive for decades, only to reappear, sometimes in a more virulent form. Take the case of the Zika outbreak. The virus has been in the country for decades. In 1954, NIV had detected the Zika virus antibody in 16 per cent of samples taken from Bharuch district, Gujarat, says Dr Devendra Mourya, director, NIV. The virus was present in a “silent, low-key ecological niche”, he says. But it was not until May 2017, when three cases were detected in Gujarat and another was later confirmed in Tamil Nadu, that the Zika scare really shook India and its public health machinery.

The detection of the Zika virus, say experts at NIV, happened only because scientists were prepared for it following the outbreak in Brazil in 2015 because the vector (Aedes aegypti mosquito) was already present in India. Training had been going on in 20 laboratories across the country, and the testing for Zika began with the first case showing up in Bapunagar, Gujarat. Alarm bells were sounded and NIV experts warned that Zika could soon become a public health concern.

It did not take very long, and in 2018, a large-scale outbreak of Zika hit Jaipur, and a month later Madhya Pradesh. Virologists say the Zika virus, named after the Ugandan forest from where it was discovered, poses several challenges. They say the virus can outsmart diagnostic tests, given its structural similarities to its close relative, the dengue virus. That is what happened with the chikungunya virus. Misdiagnosis with dengue had led to the epidemic being concealed for almost three decades until it emerged as a major epidemic in 2005.

“Both (Zika and dengue) belong to the flavivirus family, and due to cross reactivity, serological tests can show false positives,” says Dr Ullas P.T., scientist, NIV, who has been working on Zika. Antibodies from one virus can be confused with those from the other, and hence, there is a need to develop advanced, sensitive tests that are able to differentiate between the two viruses, he says. One such test is being developed at NIV. If the institute succeeds, this would be the first such diagnostic test in the world.

The structure of the virus and its mutations raises many questions. One of them pertains to the disease-causing capabilities of Zika. At NIV, experts at the computational biology section will typically amplify the virus genome, sequence it and then arrive at some clues about how weak or strong the virus is, and ascertain its damage-causing abilities. “In the case of Zika, we know it is the Asian strain, and that it does not carry the mutation associated with microcephaly that was seen in Brazil,” says Ullas.

But, he cautions, this is not to say that there could be no microcephaly in India or that the virus cannot emerge in a more virulent form in the next outbreak. “Though the mutation reported to be associated with the Zika virus that caused microcephaly in children in Brazil were not found in the Zika virus isolated from the recent outbreaks in India, these strains could be far from naive. Zika viruses have been shown to infect and damage neural progenitor cells, and infections during pregnancy can have serious consequences on the developing fetus," he says. Studies are already under way in Rajasthan, and Zika-affected cases are being followed up to assess any changes caused by the virus on a long-term basis.

The Zika virus may only cause mild symptoms—in 80 per cent of cases it does not even show any symptoms. But its greatest danger lies in the fact that it gets transmitted to the next generation, causing neurological anomalies. “Many aspects of Zika disease in humans are unclear and research is in progress to decipher it,” says Ullas.

When it comes to tracing the virus, clues are to be found outside the laboratories, too. In the case of Nipah, for instance, one of the clues was the fact that there was a cluster of cases of encephalitis among several adults in a family. After laboratory confirmation of the virus, Arunkumar and his team did several investigations on the field to trace the source of the infection. While the infection had spread from within the hospital, the big question remained: how did the first victim get the virus? The virus resides in fruit bats, but it does not usually get transmitted to human beings, says Arunkumar. “When we looked through the mobile phone of the first victim of Nipah virus, we found that the man, a plumber, had a special love for animals. One of the possibilities could be that he had rescued a baby bat that had fallen off the mother's body (April being the breeding season) and that lead him to get the infection. But we have no evidence to prove this,” says Arunkumar.

For the most part, though, virologists say that dealing with outbreaks requires detecting the viruses early through strong surveillance units in districts, analysing data to examine emerging trends, and the political will to act on the findings. For instance, from his four-year long study of 40,000 hospitalised cases of fever from across the country, Arunkumar says the team at MCVR found that in a majority of the cases the suspects are few, namely influenza, dengue, scrub typhus, leptospirosis and malaria. Besides, cases of Japanese encephalitis are seen in the north and the northeast, and Kyasanur Forest Disease (monkey fever) along the Western Ghat regions of Goa, Karnataka, Kerala, Maharashtra and Tamil Nadu.

Though India has come a long way since the Surat plague of 1996, experts say more needs to be done, given the looming threat of Middle Eastern Respiratory Syndrome, yellow fever and even the deadly Ebola virus. The ICMR’s plan to set up 150 laboratories across the country needs to be completed too—currently there are only 80—and more trained manpower is required on the ground to capture even the weakest of signs. “Clinical acumen in ground staff is also required so that symptoms are interpreted early,” says Arunkumar. "Each time we detect a viral disease early, we save on hospital admissions and thwart the spread of a deadly virus such as Nipah. As a country, we must also send our experts to work on outbreaks such as Ebola outside our borders. That will allow us to understand these diseases better, much before they hit us." Experts say that the susceptibility of the Indian population to viral, vector-borne diseases is rather high. “The war [against viruses] is on. And we need to gear up,” says Kumar.