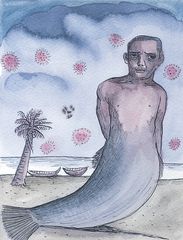

Amid all the headline stories about the impact of Covid-19—the tragedy of migrant workers, challenges faced by health care providers, the collapse of industry and so sadly on—there is one community that has been universally ignored and neglected: the fisherfolk.

Our fishing communities represent one of the most economically challenged and marginalised sections of our society. Most live below the poverty line and work incredibly hard just to stay afloat. The conditions endured by fishermen in my constituency of Thiruvananthapuram—who are yet to fully recover from the devastating losses they suffered when Cyclone Ockhi struck over two years ago—are pitiable, but they are not the only ones. The impoverishment faced by the community is a reality across the nation, and little by way of comprehensive redressal has been done for them in the last few years.

To make matters worse, for the last 40 days, most of them could not go out to fish. Many had already ventured out to sea when the lockdown was suddenly announced, but they came back and found they could not sell their catch, as the fish supply chain on land had been disrupted, with restaurants and fish markets closed. Fisherwomen could not go from house to house to sell their husbands’ catch because of restrictions. For a group that survives on a hand-to-mouth existence, their inability to conduct basic daily activities is causing significant economic trauma. With little cash in hand, they cannot buy medicines and emergency rations, or attend to existing debts.

The lockdown was instituted at a time when weather conditions were conducive for fishing, shortly before imposition of the monsoon fishing ban. This means that fishermen, anxious to make up for the losses caused by cyclones late last year and bracing for a period without income, have had to accept another fallow period. Trawlers have been pulled ashore, fishermen are idle and big city markets are mostly closed. Even fishing harbours and fish landing centres are only able to receive customers with advance bookings, and function for limited hours. Seafood is perishable, and since it could not be transported from fishing villages to consumers in the cities for weeks, it was a disaster. Most boats will have to stay off the water until the end of August.

This crisis has laid low a group of stout-hearted people who have made the nation proud through their heroism time after time. When severe floods swamped Kerala in 2018 and 2019, fisherfolk put their own subsistence aside to save marooned citizens with their boats. They joined the Navy in looking for capsized vessels and people in distress on the seas. Though barely able to make ends meet, they have always embodied the principle of selfless service. But when they are in distress, they never get the attention they deserve. That is why I nominated them, unsuccessfully, for the Nobel Peace Prize.

But they need something more tangible, something they can live on. An urgent financial package is essential for the community—some four million people nationwide, of whom 61 per cent live below the poverty line. The “fish famine” is not less than any headline-grabbing drought or calamity. A simple allowance of Rs7,500 per month to fishing families, paid into their Jan Dhan accounts, will help them cope till they can fish again. And it is not as if they do not contribute significantly to our economy. The fisheries sector contributes 1.03 per cent, or Rs1,75,573 crore, of our GDP (2017-18 figure), and indirectly provides income and employment to more than 14.5 million people.

The Central government must help this community—who were betrayed by the paltry compensatory and relief packages received after previous calamities—more substantially during lockdown. It is the very least we can do for these most vulnerable Indians.

editor@theweek.in