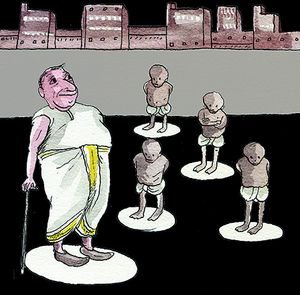

Early on in the Covid-19 crisis, I became convinced that, despite all the global protocols, we in India should not be speaking of ‘social distancing’. The phrase has become familiar because of its reiteration by the prime minister and in hundreds of memes, jokes, WhatsApp forwards and Facebook posts, featuring pictures and videos of people standing in circles and squares marked on the street to buy essential items. But in a country like ours, where society has for too long been stratified hierarchically and privileged sections kept aloof from “lesser” breeds, don’t we have too much social distancing already?

What we really needed was physical distancing, not social distancing. The latter we have practised for too long as a culture. As retired IAS officer-turned-contrarian blogger Avay Shukla wrote not long ago, “the higher castes have for centuries made it a point to keep the lower castes at a safe distance: their water sources, toilets, houses, even cremation grounds have to be in a distant corner so as not to contaminate the twice-born....” These iniquities should make us vow to end social distancing, not advocate it.

But physical distancing is another matter: it is the key to resisting the contagion. The WHO recommends that we stay three feet away from each other to minimise the risk of contamination by a cough or a sneeze. But how is a country with one of the highest population densities in the world going to ensure that? Many of our slums and poor urban areas are estimated to pack people in at 80,000 to a square kilometre. There are 4.5 lakh Indians in jails, living cheek by jowl in conditions that could turn a minor term of imprisonment for pickpocketing into a death sentence by a pandemic. We cannot, literally or metaphorically, wash our hands off them.

For some of us, the lockdown was a welcome opportunity to slow down, to rest, read and sleep (and maybe, in some cases like mine, to write). But for others, quarantine occurred in tiny apartments with packed rooms and no breathing space, no access to fresh air and few facilities for recreation or exercise. For them the risk of infection was matched by the risks of proximity, both balanced by the loss of work and income. What would social distancing mean to those who live in circumstances so overflowing with people that physical distancing is an impossibility?

Around the world, lockdowns have generated stories of social breakdown because of lack of physical distancing. News reports spoke of a dramatic rise in divorce rates in China, where couples unaccustomed to spending so much time in a confined space with each other realised that they didn’t actually relish each other’s intimacy all that much. Photos on the internet revealed long queues in the US outside gun stores, as people decided that arming themselves against their fellow men was an essential complement to arming themselves against the virus. In India, the imperative to create distance from possible sources of contamination led to unpleasant episodes—white people being ordered off a bus by fellow passengers, hotels refusing to admit foreign tourists, residential societies turning away Air India pilots and crew on their return from heroic missions to evacuate Indians stranded in contagion-affected countries. These incidents revealed unattractive aspects of our culture that will require serious rethinking once the pandemic is over.

But there were encouraging examples, too, none better exemplified than when large numbers of Italians came out onto their balconies in Milan and sang arias to one another. Such moments give us hope that however much we may seek social distancing from each other, at heart we recognise that we all need other people, and it is interacting with them that gives our lives meaning.