As health authorities around the world advise people to avoid shaking hands (and even to eschew Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s preferred bear hug) to minimise the risk of being infected by the highly contagious coronavirus, the Indian namaskaram, more commonly known as namaste, offers the preferred alternative.

This desi salutation is now quite being considered the most “virus-proof”way to greet people. While various other gestures have also been tried, many world leaders have shown a distinct preference for India’s traditional folded-hands greeting.

“Namaste goes global”, understandably chuffed Indian headlines screamed as world leaders including US President Donald Trump, French President Emmanuel Macron, and Britain’s Prince Charles adopted it on widely-televised occasions during the coronavirus pandemic. With palms pressed together and a little bow, Macron received Spain’s King Felipe and Queen Letizia at the Elysee Palace in Paris even as his ambassador to New Delhi, Emmanuel Lenain, tweeted, “President Macron has decided to greet all his counterparts with a namaste, a graceful gesture that he has retained from his India visit in 2018”.

When Trump greeted Irish Prime Minister Leo Varadkar at the White House recently, it was with a namaste. While that should have been easy for the half-Indian Irish prime minister, Varadkar said: “It almost feels impersonal. It feels like you are being rude.”

This is no small matter, since the customary handshake is what provides world leaders the usual photo opportunity that is publicised around the world to mark their meetings. Trump admitted that it was “sort of a weird feeling”to forego the handshake. Prince Charles nearly forgot during a recent meeting with the lord-lieutenant of Greater London, offering a handshake before quickly remembering to switch to a namaste. But Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu had no hesitation in recommending the Indian namaste to his fellow citizens with a demonstration at a press conference.

India is hardly alone in having devised a greeting that does not involve the vigorous pumping of hands. The Japanese have the custom of ojigi—bowing to each other, with the depth of the bowing conveying the degree of respect in a hierarchical society. Tibetans stick out their tongues in greeting, while Eskimos rub noses. In Oman, Qatar and Yemen people touch their noses in a salaam to others. Some Arabs hug each other, the greeter’s head crossing one shoulder after another. The Europeans, of course, famously kiss each other on the cheeks. But if you want to greet someone while avoiding close contact or even proximity with the other, nothing beats the namaste.

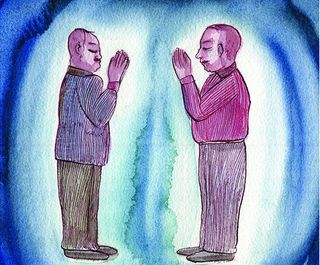

As I pointed out in a tweet, behind every major ancient Indian tradition, there is science. I should have added spirituality, since “namaste”is not just a gesture of greeting. It is one of the six forms of pranama in Hinduism and conveys that the person one is greeting, even a stranger, shares a common atman with you, so that “the divine in me bows [in greeting and recognition] to the divine in you”.

The term namaste is derived from Sanskrit, and is a combination of the word namah and the second person dative pronoun, te, in what linguists call its enclitic form. Namah means “bow”or “obeisance”, and te means “to you”. The namaste sees and adores the divine in every person, and is therefore an act of both humility and spiritual bonding.

What could be more appropriate today than this message of universal brotherhood, from the very culture that proclaimed “Vasudhaiva kutumbakam (the whole world is a family)”? As Covid-19 assails us all, we are all in this together. We share the same divinity, the same soul, and the same vulnerability. Namaste to you, dear reader—wherever you are.