Rivers don’t bend like Beckham. Nor do roads. Both are designed for movement—one for water, the other for vehicles. They meander in slow, gentle curves; no sharp cuts.

Buildings are meant for the opposite job—to limit movement, to keep you within spaces. They have sharp corners, and walls perpendicular to the floor.

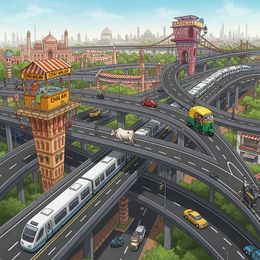

What if a road-layer makes a house, and a house-builder erects an overbridge? You’d get a house with curved corners, and a bridge with sharp turns. A sample of the latter has been built in Bhopal costing Rs18 crore; Indore is reportedly planning one with two sharp turns. Together they should give Pisa’s tower a run for its slant.

Most of India’s public utilities are Tughlaqian attempts at fitting square pegs in round holes—service lanes that take you to the wrong end of the main road, cycle tracks dotted with kerbs, ramps that look like mini Everests to the wheel-chaired divyangjan, arrow-shaped chrome-and-steel roadsigns positioned to hit New Delhi’s footpath walkers on their faces, ATM kiosks with doors that hit your behind if someone opens them (contrast them with the good old STD booths, desi copies of London’s iconic phone booths), bus waiting sheds with steel-bar seats that burn your bottoms in summers.

Leave summers; the rains are upon us. How many stations can you count where you can board a bus without getting wet? We have even airport terminals without roofs over the alighting point. Let’s be fair, square or perpendicular—train stations fare better. Platforms in major stations, built by colonial rulers, were benignly roofed up to the edge; you can still board your coach without getting wet.

Kerbs are of a standard height across most of the world—six inches in most of America—letting you park your car without the bumper hitting the kerb. How many of you have parked a car anywhere in India without ever denting the bumper?

We build utilities, structures and products. They tick all the boxes of structural engineering. We don’t design them; we don’t look at how people would use them.

Look at our Arjun tank. It has the world’s best armour (Kanchan), the best gun, the best fire-control system, the best everything that goes into a tank—superior to those in Challenger, Merkava, Abrams, Leopard or T-92. But when we put all these best things together, the tanks got fat by an inch or two, heavier by a kilo or two for our rail rakes and narrow border bridges to take them. It took years to rectify them. One of its builders told me in tears—“We didn’t have design engineers.”

Why talk of tanks? We haven’t yet designed a good car. Did someone say Indica? Where is it now? Does it have a progeny?

We may have built rockets and missiles; those are for specific use by specific persons. Not so in the case of bus waiting sheds, airports, kerbs, wheelchair ramps, bridges, cars or even tanks. They are for mass use; we don’t know how to design them.

So we put square pegs in round holes. Literally. Look at Lutyens’ New Delhi, one of the world’s best designed cities with tree-lined avenues, picturesque round-abouts, walkways and footpaths. Its basic design was rounded and radial—the old Parliament House, Connaught Place, Gole Market, Gole Dak Khana, and roads radiating from these circles crossing each other at large round-abouts. Smooth, curved, meandering, yet flowing.

Now? We have erected triangular road signs that hit pedestrians in the face, traffic lights at round-abouts as if they were squares, and a triangular Parliament House next to the old rounded structure.

prasannan@theweek.in