Working on the chain gang, no more’—was an American pop song of the 1980s. Chain gangs, if you don’t know, were groups of prisoners chained together and made to do hard labour, common in the post-slave trading US south. Norms of civilised human rights that spread in the post-war world led to chain gangs being phased out by the late 1950s.

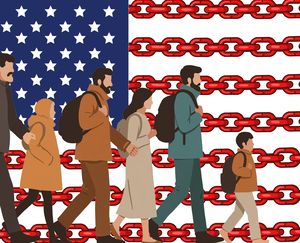

Chain gangs are back. Arizona and Alabama brought back chain-ganging of prison labour in the 1990s; now Donald Trump has okayed it to detain and deport illegal immigrants. They are sent back to their homelands in military planes with leg chains, restrained from loo visits, and fed with just apples. More than a 100 were offloaded in Amritsar last week, and the Trump regime has said there will be more.

Indeed, Trump is within his right to deport anyone—Indian or Indonesian—if he or she has entered his “land of opportunities” without valid papers. But chaining them like galley slaves and packing them like sardines in military planes? One expected the civilised world, where even handcuffing of prisoners is frowned upon by courts of law, to condemn it as barbaric.

Strangely, there was hardly any protest from India, except stray opposition voices. On the contrary, Foreign Minister S. Jaishankar stated in Parliament that was the law and rule in the US.

Jaishankar isn’t the first foreign minister to say so. Fourteen years ago, when about 1,500 Indian kids who had been duped into joining a cheat-school called Tri-Valley University were radio-collared, his predecessor S.M. Krishna had said verily the same. “There is hardly anything India can do if the US laws permit such action to track students.”

Fully agree, sirs. If that is the law in the US, and these guys violated US laws, let US laws prevail over them.

But that wasn’t how we had reacted in 2013 when consular official Devyani Khobragade was arrested in New York, strip-searched and thrown into a police lock-up for having forced a housemaid into slave labour. She, too, had violated US laws, and the US clarified that her ‘consular immunity’ didn’t give her ‘diplomatic immunity’ from arrest for crimes committed on US soil.

All that fell on Delhi's deaf ears. The PMO fumed, the foreign office fretted, the ministers frothed. India showed that hell hath no fury like a diplomat scorned. The foreign secretary protested to the US mission head, blocked her travel to Nepal; the Lok Sabha speaker shooed away a visiting Congressional delegation; the foreign office confiscated US consular officers’ I-cards, blocked their discounted alcohol imports; taxmen sought pay books of maids, cooks and gardeners in diplomats’ homes and teachers in the embassy school; cops started challaning speeding embassy cars; and a former foreign minister called for arrest of same-sex companions of US diplomats, citing the Supreme Court’s upholding of Section 377 of the penal code.

The fury shook the entire Chanakyapuri, New Delhi’s diplomatic enclave. Bulldozers rolled down its roads knocking down every security barricade that the US mission had erected around its premises. It took weeks for saner counsel to prevail, the offender transferred to a post which gave her diplomatic immunity, and sent back to India.

No one wants such frenzy to be repeated. But the least India could have done now was to register a dignified protest, and issue a mild warning that any US citizen found in India without papers could be similarly dealt with.

No such law in India? Make one, at least to make the boors in Washington know that India has cheek—one that wouldn’t turn at every slap.

prasannan@theweek.in