From where I sit, the summer afternoon is worthy of a Wordsworth. The dappled sunshine spells laziness; the buzzing of a bee heightens the feeling. Rose bushes, peonies, purple irises and wild daisies sway to the music of wind chimes. The fresh mountain breeze rustles through the willows and heads to the pines and deodars on the yonder slopes. Yet this beauty is blighted; the poison of the pandemic keeps seeping through.

Those who live through this anxious summer will remember it as a time when an unseen killer floated in the air, every passer-by its potential ally. When the sight of another human being made you instinctively tighten the mask on your nose and every sneeze drew scared glances. When it was alright for friends and family to not meet for weeks, when a wave across a fence was considered greeting enough, when avoiding close contact became a minor victory. Conversations and confidences dried up and each person began to look inwards, treasuring the simple fact of just being alive.

This will be the summer when the generation to which my children belong suddenly grew up. They started using their phones not for posting photographs of what they were eating and drinking but to help find oxygen cylinders or hospital beds or life-saving drugs for friends. Hospitals, ICUs, crematoria and virtual condolence meetings entered their carefree lexicon and death was no longer something that happened only to grandparents. They learnt too the value of doing good, in however small a measure. They realised, earlier in life than usual, the emptiness of material success and observed in impotent rage that wealth mostly meets only selfish ends. They learnt the limited reach of good intentions and the sickening helplessness of hitting your head against a wall. Their belief that a modern world will only get better has been proven false.

This will be the summer that held up an unforgiving mirror to us as a nation, and showed us, at just past three score and ten, how badly we had aged. It highlighted each wrinkle, each wart, each grotesque grimace. It showed us that time lost and opportunities missed do not come back; usually there is no bus after the last one.

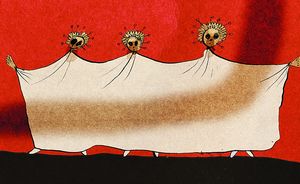

This too will be the summer when the shroud of dignity was pulled rudely off the face of death. When human bodies were just contagious garbage requiring quick disposal, in crowded crematoria, or on pavements, or down rivers, or in shallow sandbanks. When family members could watch the funerals of loved ones only as a phone recording. When the ghouls came out to steal—overcharging for ambulances or hospital beds, or hoarding oxygen concentrators, or selling essentials drugs in black. Mercifully, this too was the time when anonymous angels appeared to set up oxygen langars, build pyres for strangers and say the last prayers over unclaimed bodies, irrespective of caste or creed. Even as the darkness thickened, humanity raised its head in unexpected ways.

And this will be the summer when too many friends would have departed without a proper farewell—many before their time, if there is such a thing. When the gatherings begin again, there will be vacant chairs, and even those who are there will not be the same people. The words of Mirza Ghalib, lamenting the loss of his friends in the violence of 1857, will be on many minds:

“Hai, itne yaar mare ki jo main maroonga to mera koi rone wala bhi na hoga.”

“So many friends have died that now if I were to die, there would be no one left to mourn me.”

editor@theweek.in