Marketing gurus say that to truly have made news today, you need to have spawned a few memes about you. Actor Ranveer Singh’s nude pictures, published around two weeks ago in Paper, have generated much merriment: “Since you thought his fashion sense was ‘obscene’ take a look at him now”, or “Mumbaikars when they find themselves in Delhi during summer”, or even Myntra’s ‘Fixed It’ campaign morphing tawdry florals on his buff body.

In today’s India, unfortunately, you have not really made news unless you have offended someone’s sensibilities and invited an FIR. Yes, that is what you get for baring your soul, and a little bit of your fabulously chiseled buttock. Perhaps Singh knew he would have a brush with controversy. But I suspect he would still do it.

Singh is truly a socio-cultural study of what it means to be a young actor cracking it big in the world’s biggest film industry. He came in as a rank newcomer, without a famous last name or a godfather, and landed right on top of the pile with one of the most illustrious production houses, Yash Raj Films, backing him. With only a couple of film releases, he became YRF’s golden goose. He turned Sanjay Leela Bhansali’s Bhansali Productions and Zoya Akhtar’s Tiger Baby into major production houses by churning out blockbusters. Singh had become bigger than Bollywood itself.

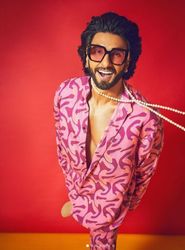

Singh understood the Instagram generation. He knew before all of us the power of digital media—where outlandish photos and videos would eclipse everything else—and gave us eyeball-grabbing images. He used flashy fashion to arrest the viewer, to provoke and to tease. His colours were psychotropic, his shapes gender-fluid and his accessories obnoxious, ensuring that his pictures were everywhere. Right from his manners to his methodology, Singh made madness his schtick. He who owns the optics, owns the audience. Soon enough, he went from town clown to king entertainer.

Singh’s fashion is as personal as it is political. Soon, he began to herald a new-age man. In Bajirao Mastani—bald, mustachioed and Brahmin-tailed—his hyper masculinity was matched with a feminine softness: flowing dhotis and diaphanous angrakhas, and as much jewellery as the film’s female characters.

This is also the year when he began to wear skirts to public events—a lehenga with a bandhgala, to be precise—and brought camp dressing to the mainstream. His designer then, Sabyasachi Mukherjee, told me this: “In India, where patriarchy decides everything, women are the biggest casualty. But one must not forget that several men are the victims of patriarchy too. In traditional joint families, rules and roles have been decided for men. Men must not cry, must not show emotion, must not show weakness. Ranveer gives these men the courage to break free.” Mukherjee had said in 2015 that how Singh dressed then would be how men dressed a decade later. In 2018, Singh played a bisexual Alauddin Khilji in Padmaavat. That was also the year the Supreme Court decriminalised homosexuality.

Singh’s personal life has also introduced us to the ideal partner. He is in absolute admiration of Deepika Padukone’s beauty and talent, a rarity in Bollywood where heroes have denied recognition to their girlfriends or hid their marriages for fear of losing female fans. Singh, as a zealous lover, was a new kind of sexy.

Nitasha Gaurav, his longtime stylist and friend, is in awe of his nude photos. “Look at him, he is at peak fitness—sinewy, polished, perfect. Almost like one of those Olympian sportsmen you see in ancient Greek art,” she says. “He is also immensely self-aware, he does not need the artifice of imposed masculinity or femininity. Clothes only enhance his being.” And his ‘being’ is being a hero for women and queers. Applaud while you ogle, please.