I was a child of television. Unlike many journalists who migrated from newspapers to the visual media, my first master’s degree was in film and television production and my first job was as a producer-reporter-sound mixer in television news.

This background is to explain that unlike others, I have never been contemptuous about television. I loved the grammar of pictures and their capacity to tell an immediate, intimate, powerful story.

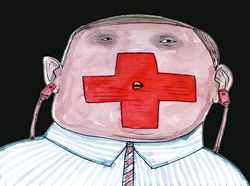

But two decades later, storytelling is dead in television news. And all that remains is variants of talk—some polite, some shrill, almost all of it banal and some of it positively injurious to the health of our democracy.

Whether it is the way the tragic death of Sushant Singh Rajput or the fatal heart attack of Congress spokesperson Rajiv Tyagi shortly after he attended a raucous television debate has been reported, the chatterbox is now way more lethal than a mere idiot box.

The problem is not just the coarsening of conversation or the political partisanship. It’s the unleashing of vigilante justice. Today there is little difference in an insane, blatantly fake forward you receive on WhatsApp and the content you may consume on television. And the uncles and aunties in your family forums believe both to be accurate. If the last distinguishing feature of mainstream media—challenged more and more by digital platforms and social networks—was editorial gatekeeping, that distinction no longer exists.

We debate toxicity and hate-mongering on our online platforms. How often do we step back and question the 9pm news? Whether it is subliminal hatred against Muslims, pronouncements of guilt and innocence against individuals, pseudo-patriotism or downright slander, prime time is now a pathetic spectacle.

Funny thing is wherever I go, people crib nonstop about the quality of news media. ‘Tamasha’ is a word frequently used for my erstwhile medium. Everyone recognises that there is barely any reportage in television newsrooms. But even the quality of talk is suspect. It’s not as if viewers enjoy seeing the same faces rotate across studios, or in the age of Covid-19, on Zoom. The most common thing I hear about TV news is how it is chasing TRPs. But no one stops to consider what a TRP (television rating point) actually is. A TRP is all of you, all of us—the audience. It is in your power to reject or accept a certain kind of news media.

Now, of course, the other big problem in an increasingly polarised polity is that of viewers seeking confirmation bias. In other words, if my programme does not confirm your political bias, you will call me partisan. Those of us who remain adamantly free from either camp get to face this even more as we get attacked by all sides.

But keeping aside political affiliations—real and imagined—for the moment, wouldn’t you want a news show that does not embarrass you, that is robustly researched and reported and that you watch for information, not for mindless entertainment?

As somebody who has migrated to the digital world from television, I know this: as a young person growing up today, I would never have become a broadcast journalist if these were the examples before me.

The future of journalism lies not just with its practitioners. It lies with we, the people—the audience.

Choose wisely.

editor@theweek.in