Sidhartha Mallya is used to being called a ‘Poor little rich boy’. As he says it in his book If I’m Honest, he has been called worse names. He addresses this put down along with many other hurtful epithets while writing about his mental health journey. I read the book over two nights, and wondered why Sidhartha chose to go public with his life at this stage. I have known the young man from the days when he was a plump, cocky schoolboy with a plum Brit accent. Behind the brash façade hid a wounded, lost child… and each time we met, I longed to assure him it was ‘okay to be not okay’ (as the popular phrase goes).

When I finished the book, I figured it was a deeply cathartic effort, which could have done with far tighter editing—surely, Sidhartha deserved that much! It must have taken enormous courage to share not just his own troubled life, but to also attach an earnest missionary zeal to the narrative. Sidhartha wants readers to better understand the process of healing, and to that extent, the book works well. When he describes what exactly is involved while dealing with obsessive-compulsive disorder, there is a huge takeaway from this information, since it is a personalised, identifiable account. Ditto for his different phases involving binge drinking, alcoholism, depression and a dependence on prescription drugs.

But most people are more interested in knowing the worst about his father. Sidhartha is acutely aware of the ‘problem’ of being Vijay Mallya’s only son (he has two half-sisters and two step siblings). While he stops short of dishing the dirt, there is enough masala in the book to pique interest.

Sidhartha would not have been this person had his life not been affected by the emotionally scarring events he was subjected to at such a young age. It is all there—his parents’ painful divorce when he was ten; the discovery of his father’s parallel family, about which he had no idea; his crippling sense of isolation as he found himself anchorless and adrift coping as best as he could, while his father went about his own adventurous life, oblivious to what Sidhartha was going through.

The message of the book is uplifting and positive. Sidhartha is not playing martyr or victim.

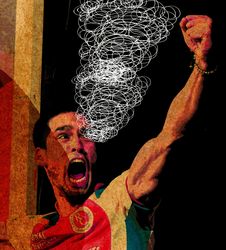

My admiration is reserved for Vijay Mallya, who must have cleared the book before it was published. Vijay does not come across as a villain, and Sidhartha’s hero worship of his father is most evident. Having known the family over decades, I could empathise with Sid’s perspective and identify his multiple traumas. When he writes about his step-mother and grandmother, or his step siblings and half-sisters, there is anger and hurt, but no malice. It is a cruel, crude and voyeuristic world out there. Sidhartha, who has relocated to L.A., where he hopes to make it as an actor, has found his own identity and voice finally. He gained a loyal following, first as a casual and very witty cricket ‘commentator’ when he made off the cuff remarks on camera during the IPL matches (his father owned the Royal Challengers), and more recently, with his well-articulated podcasts on mental health issues. The young were in sync with what he was saying, and it is to his credit that he was not whingeing or whining.

The book ends on an upbeat note with Sid jauntily signing off by thanking his dog, Duke. When a troll commented, “You look like a dog,” Sid replied, “That’s an insult to dogs.” Sidhartha has ‘embraced’ his truth. He urges readers to do the same.