While the entire attention of the country may be on the border between China and India, the attention of China’s strategists would be more on the Indian economy. One should not interpret the old Chinese saying—One mountain cannot contain two tigers—too literally. The mountain that the Chinese strategists have in mind is not the Himalayas but Asia and its economy.

The Chinese army’s repeated incursions along the Line of Actual Control (LAC)—Depsang (2013), Doklam (2017) and Galwan (2020)—should not be viewed purely as attempts at land grab aimed at securing advantageous positions in the event of a war. Many in India have become students of Himalayan geography, but the real game in Asia is for economic dominance. Of course, it is the duty of military brass to defend the border and retain control over territory. But, China’s strategy towards India has to be viewed from a wider lens, and not a purely military one.

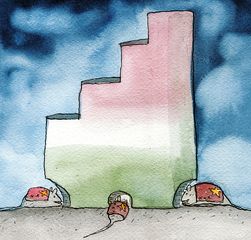

What does China want? From the plains of Central Asia to the islands of the Pacific, from Northeast Asia to Southern Africa, Xi Jinping’s China wishes to establish that there is only one Asian superpower. Sure, at the global level China still acknowledges that there is another superpower, the United States. But, Xi would want the world to acknowledge what it did at the end of World War II, that there are only two superpowers and everyone else is a secondary or tertiary player.

Indeed, most Asian nations, including Japan, have come to implicitly accept this. India, too, has stopped calling itself a ‘leading power’ and now refers to itself, along with Russia, Japan, France and so on, as a Middle Power. But Xi would want India to say that a bit more loudly.

Till around 2012, China may well have gone along with the global consensus that India too was rising rapidly and would catch up with China. After all, none other than Singapore’s Lee Kuan Yew, a friend of China, had said in 2007 that China and India were the two engines of the Asian aircraft, and for Asia to take off smoothly both engines must fire in tandem.

India’s economic growth experience, between 1991 and 2012, may have made China believe that India was capable of catching up. Till 1980 the two economies stood more or less on par, even if China had by then built a stronger base for future growth. It was assumed India was capable of again catching up.

The travails of the United Progressive Alliance II government may have made China re-examine these assumptions. The Indian economy seemed to be faltering and its political leadership seemed no longer capable of ensuring that India remained on the growth trajectory of the first decade of the 21st Century. It appears that the Chinese assessment of the six years of the Narendra Modi government is that despite its political strength it has not been able to restore momentum to the economy.

It would be wrong to assume that China only aims to bolster its tactical, or even strategic, positions along the border. In appearing to do so, and repeatedly provoking India, China seeks to keep India both politically and economically off-balance. Which means no five-point joint statement is likely to end the impasse in the relationship. The challenge before India is to regain economic momentum and bolster its economic capabilities. That alone will ensure an Asian balance of power conducive to regional peace and global security. An Asia dominated by an authoritarian and hegemonic China will never be peaceful, secure or stable.

Baru is an economist and a writer. He was adviser to former prime minister Manmohan Singh.