When H.D. Deve Gowda and S.R. Bommai occupied neighbouring ministerial bungalows on Bengaluru’s Crescent Road in the mid-1980s, both of them were aspiring to become Karnataka chief minister by displacing the firmly entrenched Ramakrishna Hegde. Their sons—H.D. Kumaraswamy and Basavaraj Bommai—were at that time busy in their professions after completing studies. Bommai Sr got lucky first. He became chief minister in 1988; Gowda followed in 1994. Both the families moved out of the Crescent Road bungalows.

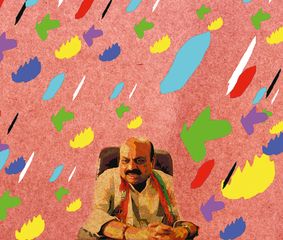

Now, Basavaraj has become the fourth Crescent Road ex-resident to become chief minister. Kumaraswamy had earlier twice become CM, while another Crescent Road ‘boy’ H.D. Revanna, who is elder to Kumaraswamy, has made it only to the ministerial level.

Interestingly, new ministers in Karnataka try hard to get one of the ‘lucky bungalows’ on Crescent Road, Gandhi Bhavan Road and Race Course Road. S. Bangarappa, N. Dharam Singh, S.M. Krishna, B.S. Yediyurappa and Siddaramaiah have all had addresses on these streets before becoming chief ministers.

Basavaraj’s interest in politics grew after his father moved to Delhi—first as national president of the Janata Dal and, later, as human resource minister in the Gowda cabinet. Though an engineer who owned a manufacturing unit, Basavaraj helped his father fight a constitutional case that resulted in the landmark ‘Bommai judgement’, in which the Supreme Court declared that the majority enjoyed by a chief minister can only be tested in a legislative assembly.

Basavaraj also launched a campaign with lawyer and Congress leader Brijesh Kalappa in Delhi, petitioning the heads of national and regional parties to retire veterans and promote young leaders. They wanted the president, prime minister and ministers to be young. Basavaraj’s petition, which did not yield immediate dividends, left his father amused.

Bommai was influenced by the radical humanism of revolutionary ideologue M.N. Roy, and he spent considerable money to reprint and distribute Roy’s books. Bommai was also a rationalist who bravely moved to the Balabrooie, a historic bungalow occupied by dewans and chief ministers. It was considered inauspicious because its last occupant, Devaraj Urs, was toppled by defectors. When Bommai met the same fate within months, the family was shocked.

Basavaraj, too, is known for drafting manifestos and programmes with a strong welfarist bend. Remaining true to his personal manifesto, he announced several welfare measures on his first day as chief minister.

The failure of the Janata experiment in Karnataka made Basavaraj realise that only the BJP was a viable anti-Congress alternative. He joined the party in 2008. Years later, he took another critical decision: not to abandon the party after his mentor, Yediyurappa, revolted and floated his own party. Known as a governance man, he went on to serve under three temperamentally different chief ministers. Even though his recent elevation is credited to Yediyurappa’s desire to have his own man at the top, Basavaraj has access to the bridges he built to Delhi when Amit Shah was BJP president.

Crescent Road residents have mostly had short tenures as chief minister, but they do gain second wind. Gowda became prime minister, Bommai became Union minister, and Kumaraswamy got a second, but rather short, term as chief minister. Basavaraj has only two years left before elections, but it could be enough to implement several of his cherished ideas. His challenges, though, are more political than administrative—uniting a party deeply divided into loyalists and critics of Yediyurappa, and into old-timers and new defectors. His choice of ministers and portfolios would be the big test of how effectively he can deal with heavyweights in and outside the BJP.

sachi@theweek.in