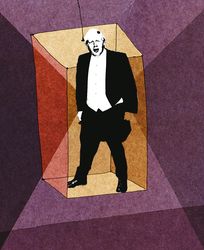

In politics, nothing changes… until it does. British commentators wonder whether Prime Minister Boris Johnson will be ousted by the current “sleaze scandal”. But Teflon Johnson, so far, has had the devil’s luck. Nothing sticks. The string of controversies, sweetheart arrangements, dodgy deals, gaffes, scandals over rewarding cronies, appeasing donors and breaking rules have failed to turn into a noose to cook his goose. Instead, he stumbles blithely—some say recklessly—into the next minefield. “He’s always had the idea that rules don’t apply to him,” says Sonia Purnell, his biographer.

The sleaze row centres around his Conservative members of parliament taking well-paid “second jobs” as lobbyists to promote private interests. Labour leader of the opposition Keir Starmer accused minister Owen Paterson of snagging Covid-19 testing equipment contracts worth £500 million for the firm Randox that paid him £1,10,000 in fees.

Parliament’s standards committee ruled against Paterson, asserting: lobbying is permitted; “paid advocacy” is not. Johnson’s initial reaction was to protect Paterson—and other Tories—by replacing the independent committee with a new one packed with his loyalists. The uproar culminated in Paterson’s resignation and Johnson backing down on his controversial proposal—his 43rd U-turn in two years in office.

Media investigations reveal over a quarter of Tory MPs have “second jobs” earning them £4 million since the pandemic began. Another scandal involved Tories “selling” peerage or seats to the House of Lords for

£3 million apiece.

Johnson himself has been embroiled in ethics inquiries into who paid for his posh Caribbean holiday, refurbishing his Downing Street flat and whether he misused his position as London mayor to benefit an American businesswoman with whom he had an affair. Starmer accused Johnson of “leading his troops through the sewer”.

But British sleaze is “chicken feed” (a favourite Johnson idiom) compared with the corruption in autocracies, poor resource-rich countries or even some southern European nations. Britain scores well, 11, on Transparency International’s ratings. But TI’s Steve Goodrich admonishes, “Where rules aren’t followed and there is no consequence, the absence of accountability can breed particularly egregious behaviour that could easily slip into out-and-out corrupt practices that you might expect from less-established democracies.”

“Petty corruption” has always existed in Britain. Whether it was MPs cheating on their allowances or the Egyptian billionaire and father of Princess Diana’s boyfriend, Mohamed Al-Fayed, slipping brown paper envelopes with cash to Conservative MP Neil Hamilton in 1996. But Professor Mark Knights, an expert on the history of corruption, compares the Johnson regime’s “new corruption” to the “old corruption” of the 18th century prime minister Robert Walpole, when government jobs were bought and sold. Knight warns, “There are signs that we could be slipping back into a Walpolean era where patronage, patrimony and partisanship prevail”.

It is unlikely that the scandals will cost Johnson his job yet. His party is solidly behind him because he is the best Tory vote-catcher. He is still an election asset, not a liability. He keeps the Conservatives’ patronage system in power. For a politician, losing the ability to win votes is like Samson losing his hair.

While Labour is nowhere close to the victory line, the sleaze row has dented Tory and—especially Johnson’s own—popularity.

Should the ratings keep falling, knives will be sharpened. Margaret Thatcher had won three elections for the Tories. When her popularity began sinking, it was her own ministers who tossed her out. Losing votes and losing money have perilous trajectories. Dwindling popularity is like bankruptcy; it happens gradually, then suddenly.

Pratap is an author and journalist.