On March 1, 1974, chief minister D. Devaraj Urs implemented a revolutionary land reform that helped thousands of landless tenant farmers in Karnataka take ownership of the fields they had been cultivating. As land was redistributed among the poor to free them from exploitative tenancy laws and absentee landlords, a slogan resonated across the state—Uluvavane bhoomi odeya, or the tiller is the owner of the land.

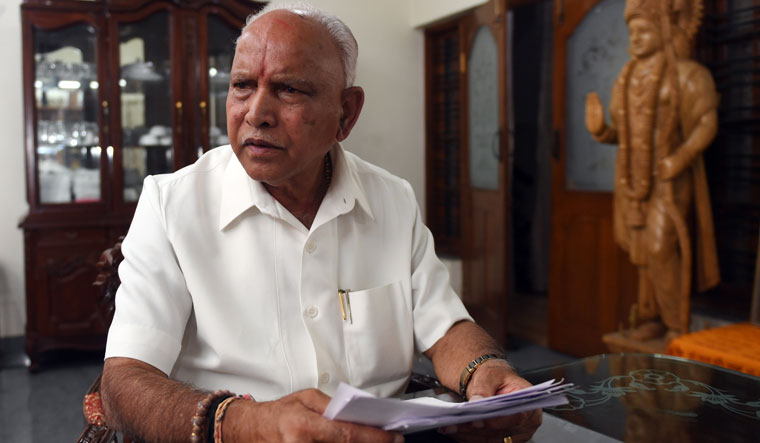

Forty-six years later, the state government led by Chief Minister B.S. Yediyurappa has brought about another set of game-changing land reforms. On September 26 this year, the assembly passed, by voice vote, the Karnataka Land Reforms (Second Amendment) Bill, replacing an ordinance promulgated in July this year. The amendment lifts restrictions on buying agriculture land, and repeals certain sections of the parent act of 1961, which bars non-farmers from buying farmland and penalises those who falsely claim that they are eligible to own farmland.

Opposition parties allege that the amendment reverses decades of farm reforms and imposes a “modern-day zamindari system” on farmers. They have been supporting statewide protests by farmers, dalits, labour organisations and pro-Kannada outfits, which want the amendment and the farm bills recently passed by Parliament to be withdrawn.

Farmer organisations say the amendment will force small-scale farmers to sell their land and become labourers. “Instead of encouraging farmers to sell their land at competitive prices, farming should be made remunerative,” said Kurubur Shantakumar of the Karnataka Rajya Raitha Sangha. “More than 19,000 applications from landless farmers seeking land are pending before the government. The farm bills are all moving towards privatisation of agriculture. The food production in the country today is 285 million tonnes, enough to last the next two years. The farmers have toiled hard to ensure food security. The government should not forget this.”

The BJP maintains that the reforms would help farmers embrace technology, enhance production and solve the agrarian crisis. “The new act will help bring a new era of farming. Many youth, including software professionals, want to engage in farming today,” said Revenue Minister R. Ashok. “Many are buying land in neighbouring states that do not have restrictions. We want farmers to adopt modern techniques to scale up agri exports, which will make farming remunerative. Right now Karnataka’s share in agri exports is only 5.7 per cent; Gujarat’s is 17 per cent.”

The Yediyurappa government has accomplished what the Union government could not in 2015. The Centre had tabled a bill in Parliament to amend the 2013 Land Acquisition, Rehabilitation and Resettlement Act, but strong opposition forced it to refer the bill to a joint house committee. Industry bodies say the stringent consent and compensation provisions in the 2013 act have resulted in land acquisitions coming to a standstill. The Union government, which is struggling to build smart cities and develop highways and industrial corridors, is banking on BJP-ruled states to push through land reforms.

Opposition parties allege that such reforms would “corporatise agriculture” and put India’s food security at risk. “Before the green revolution, the food production in the country was about 50 million tonnes,” said former chief minister Siddaramaiah. “But now, it is 291 million tonnes. But if farmland is [used for other purposes], it might lead to food scarcity. This has exposed the nexus between the government, corporates and housing societies.”

Karnataka has 195 lakh hectares of land, of which 30 lakh hectares are forest land, 22 lakh hectares are designated agriculture land, and 11.79 lakh hectares are lying fallow. The government says the new act will encourage industries only on fallow land. Irrigated farmland and land owned by dalits will continue to be protected, said Yediyurappa.

Industries bodies say the fear of farmers losing their land to corporates is unwarranted. “Till now, all industries in the state have together used less than 1 per cent of the total land and created one crore jobs,” said C.R. Janardhana, president, Federation of Karnataka Chamber of Commerce and Industries. “With the new law, industries can utilise another 1 per cent and create one crore more jobs.”

The state government is finalising a new industrial policy, focusing on 13 major sectors like automobiles, pharma, cement, steel and logistics, to help turn Karnataka into a “factory of the future”. “The policy will attract investments worth Rs5 lakh crore that can create 20 lakh jobs,” said Yediyurappa.

On March 19 this year, the state government amended section 109 of the Karnataka Land Reforms Act, 1961, allowing industries to sell agricultural land converted for industrial use after seven years. It also granted “deemed approval” for purchase and change in land use—if the state high-level clearance committee failed to file objections within 30 days.

The land bank created by the Karnataka Industrial Area Development Board has not been very helpful, say investors. At least 140 proposals worth Rs50,000 crore made in the past five years have failed to take off because of acquisition hassles. “The poor ranking of the state in ‘ease of doing’ business was mainly because of scarcity of land and red tape,” said Janardhana. “Telangana and Andhra Pradesh developed at our expense owing to the free access to land there.”

Ashok said the farmers could get competitive prices only in an open market. “In 1974, the great farmer leader Prof M.D. Nanjundaswamy favoured the scrapping of sections 79(a) and (b) [of the 1961 act], saying it was unconstitutional as it violated Article 19(g) [the right to practise any vocation]. I believe the farmer should have the right to sell his land like any other asset,” he said.

He also accused the Congress of double-dealing. “The 1961 Act was amended 34 times,” said Ashok. “Many stalwarts of the Congress, including R.V. Deshpande and Mallikarjun Kharge, had argued in favour of repealing sections 79(a) and (b). In fact, the Congress government in 2015 had attempted to scrap the sections by setting up a cabinet subcommittee. An amendment in 2017 raised the non-agricultural income limit for the buyer from Rs2 lakh to Rs25 lakh per annum.”

The Janata Dal (Secular), which counts farmers as part of its support base, is playing both sides. JD(S) leader and former chief minister H.D. Kumaraswamy has supported the new reform, saying he too had faced difficulties in buying agriculture land. But the party has extended its support to the farmer agitation as well.

Land distribution patterns show that the opposition to lifting restrictions on selling farmland has been weakening. Land values have been spiralling upward, and the average land holding in the state is 1.55 hectares now, down from 3.5 hectares in the 1960s. Large tracts of farmland are entangled in legal battles. “The state has 73,173 cases of violations under the 1961 Act, which will be abated with retrospective effect,” said Ashok.

As per the 2015-16 agriculture census, there are 78.32 lakh farming households in the state. Around 66 lakh are small and marginal farmers, holding less than 1.45 hectares. One in five rural households in the state are landless, suggesting that a huge number of farmers are still employed as farm labourers.

“Farmers are not foolish. They now understand the value of their land, especially if it is in the irrigation belt,” said Ramakrishna Omkar, a farmer in Vijayapura district. “If corporates buy land and start farming on a large scale, we, too, will benefit, as they bring new technology and a bigger market for local produce. Small farmers can till their land and work for the corporate farms or agro-based industries for additional income. It is a win-win situation.”