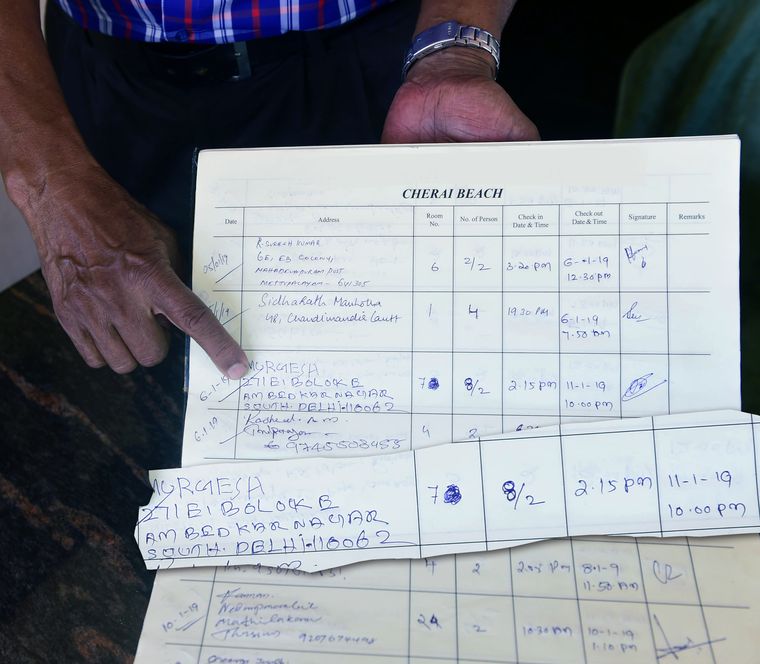

Four men and four women, with two children, checked into a budget resort near Cherai beach, 25km from Kochi at 2:15pm on January 6. One of the men handed in his identification card. The resort owner entered the details in its register—Murugesh, 27/E1, Block E, Ambedkar Nagar, South Delhi, 110062—and allotted them room 7, a dormitory. Later, they moved into four different rooms. The resort owner said he did not mark this change in the register, which, however, bore signs of something being crossed out.

The owner said that every day he collected the rent—the tariff is around Rs. 1,400 per night—in advance, as the group “did not look well-off”. Predictably enough, one of the men told him on the morning of January 11 that they could no longer afford the resort’s restaurant. Could he have some kanji (rice gruel) made for them, if they brought rice, the man asked. He added that they would check out at 10pm. The owner had the staff make the gruel for them. The next morning, he found that they had left.

Within a day, there were rumours that a human trafficking team was operating from Munambam fishing harbour, 6km away. A few days later, the Kerala government stated that it was a case of illegal migration, not human trafficking. The migrants were suspected to be Sri Lankan Tamils, and a local fishing vessel was found to be missing. And, on January 15, the Kerala Police sealed six resorts and home stays in and around Cherai beach.

Bags and the baby

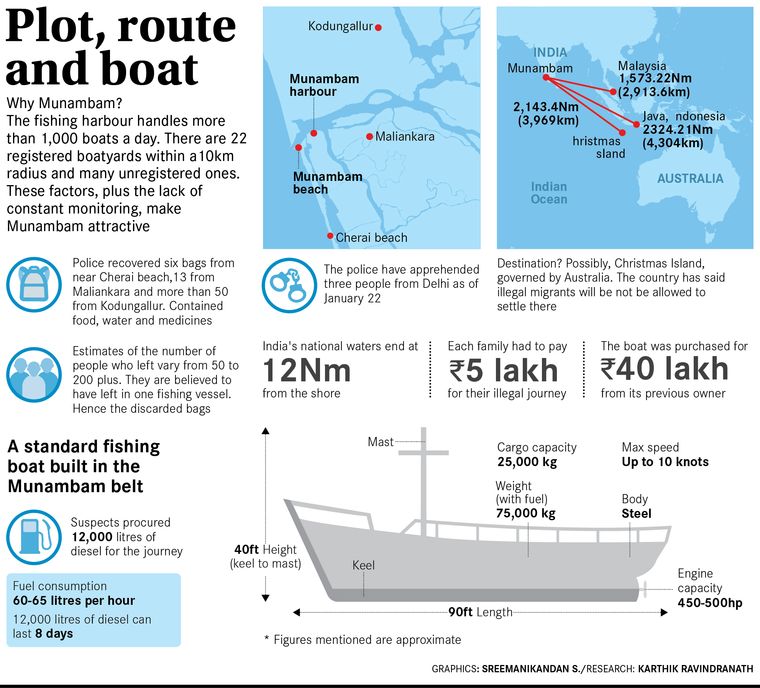

Investigations started in earnest when residents of Maliankara, around 10km from Cherai beach, informed the police about a few abandoned bags. The police found 19 bags—six from near Cherai beach and 13 from Maliankara. They contained food, energy drinks, dry fruits, biscuits, medicines and bottled water. Then came the discovery of 54 abandoned bags in Kodungalloor, 13km from Cherai beach. Convinced that a greater game was on, the police spread out the net—and stumbled upon the baby.

The police found that about 80 people from Ambedkar Nagar, South Delhi, had stayed in four lodges in Chottanikkara, about 40km from Cherai beach, from December 26, 2018, to January 4. A woman from this group, the police found, gave birth to a baby girl (3.2kg) at a hospital there on January 1. The newborn was taken to a hospital near Cherai beach when the group was staying there. The parents produced vaccination records from the Chottanikkara hospital and asked for preventive medicines, saying they were planning to “travel to Delhi by train”.

The gynaecologist who delivered the baby told THE WEEK that the mother—Pooja Babukumar, 25—had told her that they had come from Delhi by train. “We were quite surprised as she had completed her term of 38 weeks,” said the doctor. “She said she had travelled to fulfil a nercha (vow) at the Chottanikkara temple. We did not question her further because she was already in labour. She gave birth normally.”

The doctor recollected that the woman had said that her first child was 10. “I asked her, ‘How come you had a baby at the age of 15?’ She said she had got married at a very young age, as soon as she had her menarche,” the doctor said.

The doctor said Pooja sought to be discharged soon after the delivery, as they had to return to Delhi. The doctor advised her to stay back for one more day at least. Pooja’s relatives visited her in the hospital and promptly paid the hospital bill of about Rs20,000. The doctor said the woman wore ornaments and “looked well-off”—quite unlike how the resort owner at Cherai had described the group from Ambedkar Nagar.

The Delhi connection

An underbelly of South Delhi, “the Madrasi Colony” is at the end of a narrow road near Central Market in Ambedkar Nagar. Though the people here said that they did not know much about those who came to Kerala, there was a glimmer of hope in their questions: “Have they reached there?” And concern, too: “There was a rumour that the boat sank. Is it true?” The people who left had sold everything to pay the agents. Apparently, some illegal migrants who had made it to Australia in the past had managed to prosper. But, money was not the only motivation. Apart from pitiable living conditions, Ambedkar Nagar is no place for families. A policeman was stabbed here last December, while trying to prevent a robbery. Homicides and assaults on women are common. Not surprisingly, residents were reluctant to share information with the Kerala Police team probing the Munambam case.

Soon enough, however, investigators apprehended two men who had allegedly returned from Munambam after being unable to pay the full fee—Rs5 lakh for a family. The two men, Deepak, 39, and Prabhu Danthavani, 31, said that they had paid Rs3 lakh and put their wives and children on the boat; they were promised a passage the next time, on payment of the remaining amount. They said the boat carrying their wives and children left at 6am on January 13, though earlier reports had mentioned that the boat had left on January 12. Sources said the Indian Navy had received a request to search for the boat before January 13.

There was also confusion about the number of people on the boat. Deepak and Danthavani said it was carrying 230 people, and that the bags had been abandoned to make room for passengers. They also named the agents: Thiruvallur Ravi, Selvam and Thakkala Srikanth.

The boat and the builders

Srikanth’s name had come up earlier as the co-owner of the Dayamatha, the fishing vessel that is suspected to be carrying the illegal migrants. Reports said that Srikanth and his associates had bought her from an Ernakulam resident for Rs40 lakh on January 7. Superintendent of Police Rahul R. Nair said it was too early to share more details of the case.

Some reports doubted whether the Dayamatha could carry 230 people, but boatbuilders in Munambam said it could well carry so many people. The narrow snake boats of Kerala, which are 100ft to 120ft long, can carry 90 to 110 oarsmen. In contrast, the Dayamatha is a 90ft-long, sea-going trawler powered by a 490hp engine. Under the decks, there is ample space for storing fish and ice. Boatbuilders also said that her chances of making landfall in Australia or New Zealand were high. There would be a logistical challenge, though: diesel.

Adiparambil Sanilan, merchant marine-turned-boatyard owner, said a 490hp engine would need around 60 litres of diesel an hour. Reports said the agents had bought 12,000 litres of diesel from a fuel station in Munambam—just enough for about eight days of sailing. If the smuggling network is wide enough, the trawler can be refuelled by other vessels on high seas.

The Munambam area has been known for illegal migrations. In 2015, the Kerala Police busted a racket that was trying to transport Sri Lankan Tamil refugees to Australia via Munambam. Two years earlier, 30 illegal migrants from Bangladesh were caught here. In 2008, the Tamil Nadu police seized a boat which was being built for the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE). Though the owner was declared innocent, the boat has not been released and is at a private boatyard in Munambam.

Said V.S. Soliraj, a local politician, “Outsiders come here to have boats built. These boats are bigger than permitted limits [85ft and 250hp], and are built at illegal yards. The diesel tanks are as big as a tanker lorry. And, there are no records about the buyers.”

But, there is a reason why the boats are big, said Fredy Philip, president of the Muziris Deep Sea Boat Builders and Repair Association. “The fish are in the deep sea,” he said. “An 85ft vessel is not sophisticated enough to go there. Fishing should expand into deep sea. If we do not tap these resources, they will be lost. This is not a pond we are talking about. It is a 7,500km [-long zone] from West Bengal to Gujarat and 200 nautical miles from the shore.”

He said the association had petitioned the state government to raise the ceiling on boat size and power. “The state has sway over only 12 nautical miles off the coast, the other 200 nautical miles are under the Central government,” said Philip. “The skill of the builders here has been acknowledged with orders for boats coming from other states, too.”

He said traditional fishermen were also using these vessels because catch was low along the coast. And, under the Central government’s Blue Revolution project, 50 per cent subsidy is given to trawlers capable of deep sea fishing, without any cap on size and power, said Philip. He suggested that boatyards should be regularised and illegal boatyards shut down to prevent misuse of large vessels.

Waypoint: Indonesia

The fate of those who had set sail from Munambam is not clear yet, but there are pointers from the past. Benny Mathews, a Jakarta-based Malayali businessman who is president of Kerala Samajam Indonesia, is often called in by local authorities to help communicate with stranded illegal migrants. “Earlier, there used to be Afghanis, but now most of them are Sri Lankan Tamils,” Mathews told THE WEEK. “I can speak a little Tamil, so I talk to them and we [the Indian associations in Indonesia] do our best to help them with food, water and medical aid.” After Sri Lankan Tamils, Rohingyas form the biggest group of illegal migrants, he said. As Indonesia has the world’s largest Muslim population, local residents are more compassionate towards the Rohingyas.

Illegal migration is a big issue in Indonesia because it is the world’s largest archipelago and it sits on the world’s busiest shipping lane— the Malacca Strait. Mathews said most economic refugees were bound for Australia. “If they reach Australian territory, like Christmas Island, they seek asylum and the Australian government becomes responsible for them,” he said. “Even though they have to live as asylum seekers for a decade or two, they may eventually get citizenship.”

When THE WEEK contacted Australian authorities for clarity on the policy in such scenarios, the spokesperson from the department of home affairs refused to “comment on operational matters”. In 2015, Australia had made it clear that people who attempt to enter the country illegally by sea would not be allowed to settle there. Earlier, illegal migrants were intercepted and transferred to regional processing centres in Nauru or Manus Island in northern Papua New Guinea. The centres on Manus Island and Christmas Island have now been shut down.

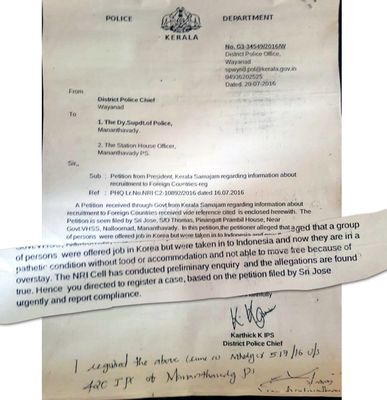

Mathews has observed two types of refugees. “One type is duped into paying lakhs of rupees with the promise of foreign jobs,” he said. An example is Jose P.T., 45, from Mananthavady in Kerala’s Wayanad district. In 2015, agents took Rs5 lakh from him, promising him a job in South Korea. He was flown to Batam, Indonesia, as part of a 30-strong group. They were given rations now and then; local contacts kept assuring them that their jobs were being arranged.

“We waited for a month, but then our visas expired,” said Jose, who now works in a shop. “Three of us got our passports back from the local agents. We contacted the NRI associations. They paid our fines and sent us back home. Those who had lost their passports were issued travel permits by the Indian embassy.” The Wayanad district police chief has informed the Mananthavady deputy superintendent of police that a preliminary inquiry made by the Kerala Police’s NRI Cell had found Jose’s complaint to be true (see letter).

The second category of economic refugees consists of people found stranded on ships and boats. These people travel without papers, aiming to become asylum seekers. “The agents seem to have international networks, because there are support ships [to provide food, water and fuel for the boats],” said Mathews. “At times, the boat crew escape on the support ships, abandoning the refugees at sea.”

Within this second type of illegal migrants, there is a section that seems to be funded by unknown benefactors. Mathews has interacted with two such groups, both comprising Sri Lankan Tamils. “They said they do not know who funded their voyage,” he said. In these cases, the involvement of LTTE sleeper cells in India cannot be ruled out. The cells could be aiming to help the Sri Lankan Tamils settle abroad and tap them for funds later.

The hunt

The Kerala government had requested the Coast Guard and the Indian Navy for help in tracking the Dayamatha. Commander Sridhar Warrier, defence spokesperson for Kerala, told THE WEEK that six to eight Naval and Coast Guard ships were involved in the search at one point. A Boeing P-8I long-range maritime patrol aircraft and Coast Guard aircraft were also deployed.

“Input that their destination could be Australia was received later,” Warrier said. “But there was no clarity on the route. They could have gone directly by boat, they could have hopped on to a ship at sea, they could have gone to Indonesia or Malaysia first and then gone on. So these possibilities were included, but search could not be restricted to that area.”

There are also jurisdiction limits. India’s national waters end at 12 nautical miles from the shore. Up to 200 nautical miles is the exclusive economic zone, where India has rights over marine resources. Beyond that, unless there is a threat or attack, the Navy cannot intervene. Reports say that Australia’s department of immigration and border protection has instructed the Australian Border Force to search for the Dayamatha.

“We have gathered enough proof on [the illegal migration attempt] and have passed on the information to the home ministry and the ministry of external affairs,” said an official at the Kerala director general of police’s office. According to him, the entire operation was planned in Delhi. He said the Union government should coordinate the investigation as it involved various states and a foreign country. “It also underlines the need for improving the constant monitoring of country’s long coast,” he said.

On January 22, the police arrested one more person of Tamil origin from near Ambedkar Nagar; Ravi Raja, 31, was named by Danthavani during interrogation. The police said that Raja was accused in more than 20 criminal cases, that he travelled to Chennai regularly and that he had links with illegal migration agents.

Now, how did the Dayamatha manage to clear both national waters and the exclusive economic zone? The best place to hide a book is in a library, see! Fishing trawlers from Kerala have a distinct colour pattern: blue hulls and orange cabins. Painted in the same colours, the Dayamatha hid in plain sight amidst the fishing fleet off the coast. And then gave the slip, possibly under the cover of darkness.

WITH RUBIN JOSEPH/Delhi & CITHARA PAUL/Thiruvananthapuram