There were no signs of the turmoil to come when India won the opening Test against Australia in Perth. Jasprit Bumrah, captaining in the absence of Rohit Sharma, showed strong leadership and extraordinary bowling form, destroying the Australian top order in both innings.

However, the joy was short-lived. Australia regrouped swiftly to win three of the remaining four Tests. This was a double whammy for India―not only did they lose the Border-Gavaskar Trophy after a decade, but also lost out on a place in the World Test Championship final for the first time since it started in 2019.

The contest was taut, drawing record crowds to make this a blockbuster series, in terms of attendance and profits. Official figures put the on-ground spectatorship at more than 8,37,000 for the five Tests, reportedly the fourth highest-ever in Australia, including the venerated Ashes contests.

This established the burgeoning appeal of the Indo-Aus rivalry, which is equal to if not greater than the Ashes currently, highlighted by some extremely close bilateral Test series, and a WTC and an ODI World Cup final, both won by Australia. Even with this Border-Gavaskar Trophy, the Australian victory was not as easy as the 3-1 scoreline suggests. India fought hard, keeping themselves in contention to at least square the series till the last innings of the fifth Test.

By regaining the trophy, Australia have dislodged India as the world’s best cricket team of the last decade across formats. In 2021, Australia had won the T20 World Cup, too, to make it a hat-trick of ICC trophies within two years.

In the end, the Aussies prevailed, not so much because of home advantage, rather because they showed greater resolve, gumption and ambition to win critical passages of play that decide the fate of a match.

India, on the other hand, tended to lose their focus under pressure, as highlighted by batting collapses, loose bowling and dropped catches.

In hindsight, these are the factors that contributed to India’s downfall.

Fickle tactical approach

There was no consistency in strategic thinking, which seemed to swing and swerve from session to session, day to day, match to match. The fact that Sharma missed the first and last Test might have had a role to play, of course, but it was in the wider, backroom planning that India seemed to be unclear.

This led to frequent changes in the playing XI as well as in the batting order, which made it difficult for the team to settle. For instance, in the first three Tests, India played three different spinners. In the fifth Test in Sydney, where a spicy, grassy pitch was screaming for an extra pacer, India played an extra spinner to shore up the batting rather than looking to take wickets. The second spinner, Washington Sundar, bowled only one over in the match.

In the batting, Sharma moving up and down the batting order would have been disorienting for K.L. Rahul, who had started the series well as opener. The ploy did not work, and in fact pulled down the batting performance further.

R. Ashwin’s decision to retire and return home midway through the series could only have added to the confusion in the dressing room, whatever the diplomatic explanations offered by Ashwin himself and the team management.

Also, for some reason, the team got sucked into avoidable issues that had no real bearing on cricket. Like Kohli’s run-in with the media in Melbourne, or Ravindra Jadeja “ducking” interview questions.

There was also the wholly avoidable episode of Kohli shoulder barging debutant Sam Konstas, which turned public favour―the Aussies had supported India’s performances till then―against the team and also made the opponents take their effort a notch higher.

What value has the support staff brought to the team is a question a number of former players, including Sunil Gavaskar, raised. The former captain demanded to know, quite rightly, why, given the specialist coaches under head coach Gautam Gamhir, Kohli’s technical flaw―of poking at deliveries outside the off stump―could not be sorted out. And also why the bowling coach could not curb the number of no balls India bowled.

All said, the biggest drag on the team was the utter failure of Sharma and Kohli. As in the home series against New Zealand―which India lost 0-3―they looked completely out of sorts against the Aussies. There, their failure had come against spin; this time, against pace.

Sharma, who missed the first Test for the birth of his second child, made a piddly 31 runs in five innings. He rested himself for the last Test, which was a thinly veiled way of saying that he had dropped himself.

Kohli’s scores were not as low as Sharma’s, but if anything, his struggle was more pathetic. Leaving aside the century in the first Test, he could muster only 90 more runs in the eight other innings. Worse, he was often dismissed in the same fashion, edging to the slip cordon or to the keeper.

Whether this was because of a flaw in technique, mental burnout or both, became the subject of widespread discussion across the cricket world.

Kohli looked a pale shadow of the dominant batter who had strode cricket grounds all over the world for a decade before the unending lean trot set in a few years ago.

The tepid form of the next rung of experienced batters―Rahul, Jadeja, Shubman Gill and Rishabh Pant (all having played in Australia previously)―affected India’s chances further.

The silver lining

Bright spots in the batting were 23-year-old opener Jaiswal (on his first tour of Australia, and now India’s premier batter) and 21-year-old debutant Nitish Kumar Reddy, who made an instant impact with his uninhibited batting supplemented by his swing bowling and brilliant fielding.

Rise of a colossus

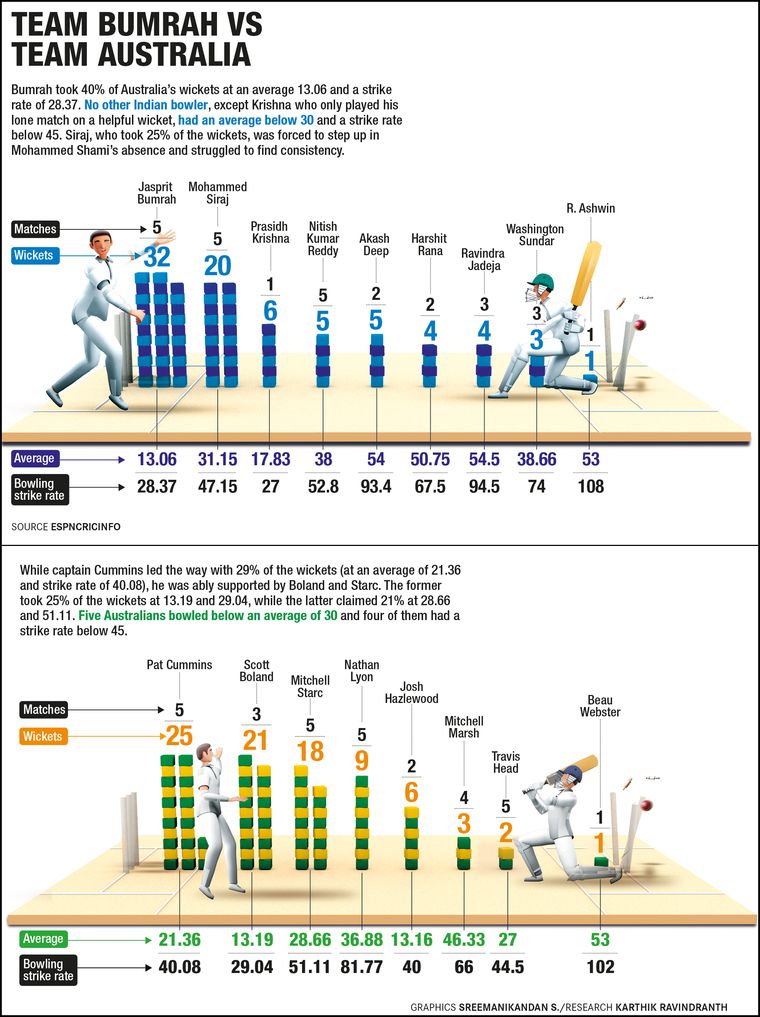

Though he finished on the losing side, Bumrah was the standout player of the series. He kept India’s hopes alive with a tour de force performance that fetched him a whopping 32 wickets.

There are a fair number of bowlers who have taken more wickets in a series, but few have done so with such a mind-boggling average (13.06) and strike rate (28.37). In many ways, the series could be described as Bumrah versus Australia.

It is moot whether India could have squared the series had Bumrah been fit to bowl in the last innings of the series at Sydney, but clearly the Aussie batters breathed more freely not seeing him at the top of his run-up.

In under eight eventful weeks, Bumrah went from being a premier fast bowler to an all-time great. His unorthodox action, immaculate control, wide repertoire of skills, probing lines and lengths, and unrelenting aggression mark him out as an exceptional talent.

Unfortunately, Bumrah’s virtuosity found meagre support from his team, especially from the batting, which looked strong on paper, but was as resilient in the middle as roasted pappadum.

What next?

India have lost six of their previous eight Tests, including three at home. This throws up multiple questions about India’s prowess in red-ball cricket as well as the future of several star players, particularly Sharma and Kohli.

In bowling, the biggest concern is Bumrah’s back spasm that kept him out of the last day’s play in Sydney. How this latest injury impacts his workload in Tests will vex the selectors as they plan for India’s Test campaigns this year.

Meanwhile, the other pace ace Mohammed Shami is still in rehab. Even if there is a plethora of fast bowlers to choose from, the pace attack looks bereft of depth, despite the feisty and tireless Mohammed Siraj.

In spin, bowlers of Ashwin’s calibre are not easily replaced. Poor returns for Jadeja in recent Tests make the slow-bowling department look thin.

The harshest scrutiny, however, will be trained on Sharma and Kohli. Age is cited as a major reason for their decline, but there are a number of players who played when much older. Their absence from domestic tournaments like the Ranji and the Duleep Trophy and the ‘superstar culture’ that guarantees players a place in the national team have become a raging debate that could lead to a change in BCCI policy.

But while India’s talent pool is rich, players such as Sharma and Kohli are not easily replaced. The intrinsic class and body of work achieved over several years cannot become the victim of mindless fulmination or senseless selection hacking. However, after this debacle, the two will have to live on current form rather than past glory, as had been the case so far.

That Indian cricket is in a state of transition is undoubted. How and at what speed this transition takes place remains to be seen.