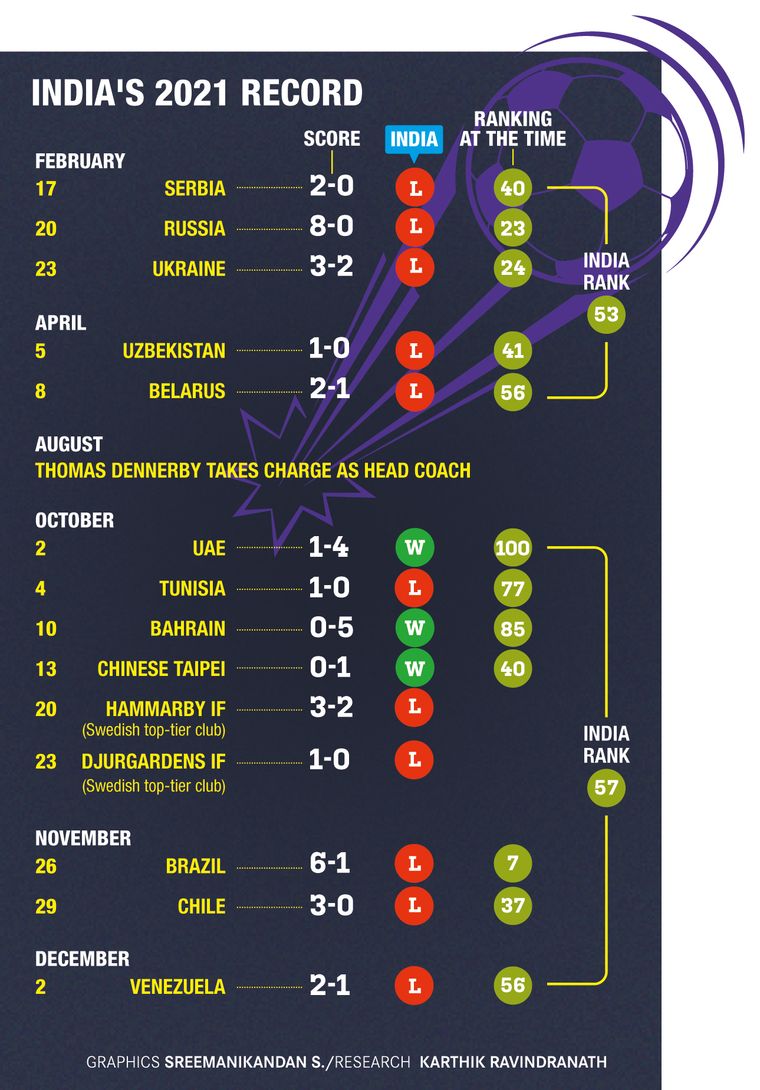

THE YEAR 2021 began badly for the Indian women’s football team. Before head coach Thomas Dennerby took charge in August, the team’s record was: Played five; lost five; three goals scored; 16 goals conceded.

Under the Swedish coach, the record till December reads: Played nine; won three; lost six; 14 goals scored; 17 goals conceded. The improvement in performances is evident, especially from the goals scored.

Of the six matches lost under the new regime, three were against South American national teams and two were against top-tier Swedish clubs (both Dennerby’s former employers). Against Asian opponents, India won all three matches, scoring 10 goals and conceding only one (see graphics).

The most noteworthy result was the 1-0 win against Chinese Taipei in October—the team was then ranked 17 places above India. The result becomes even more relevant in the run-up to the 2022 AFC Women’s Asian Cup in India as Chinese Taipei is in Group A alongside the home team. The other two teams in the group are China and Iran.

Going by the latest FIFA rankings, China (19), is the strongest team in the group. Chinese Taipei sits 16 spots above 55-ranked India; Iran is ranked 70. Therefore, India’s match against Chinese Taipei on January 23, at Navi Mumbai, would be key in determining the fates of both teams in the competition, which is scheduled to start on January 20 (India’s first match is against Iran at 7:30pm).

“One of the key qualities of this team is that the players are fast, and we can beat a lot of opponents with our pace,” said Dennerby. “Finishing and creating chances are areas we have been working on.” Both the speed, which Dennerby has repeatedly emphasised, and the work being done on finishing are becoming increasingly visible in the team’s performances.

In the win against Chinese Taipei, for instance, forward Renu (who uses only the given name) ran on to a mistimed back pass and beat the goalkeeper with a sublime chip from well outside the box; it was also from an angle—she took the shot from India’s left flank.

The 20-year-old from Haryana, who idolises Cristiano Ronaldo and India captain Sunil Chhetri, has taken her goal and the team’s win in her stride and said that Chinese Taipei were a difficult side to play against. She added that playing against European and South American teams were invaluable experiences. “They grow up playing a high level of football,” Renu told THE WEEK. “The teams in Sweden posed a physical challenge and the South American teams were technically far superior.”

The first of the South American teams that India played was Brazil (rank seven)—the first time any Indian team had played against a senior side of the Selecao. It was an exciting moment for Indian football as the home team, in its legendary yellow and blue kit, kicked off the match, on November 26, against the saffron-clad Indians. Four passes and 50 seconds later, Brazil scored. Given the gulf in quality and experience, the early goal was perhaps to be expected. What was not expected, however, was Indian attacker Manisha Kalyan’s clinical left-footed finish seven minutes later. India restricted Brazil to 2-1 in the first half, before losing 6-1.

Despite the scoreline, there were plenty of takeaways; from the goal—the result of a swift counterattack—to some determined defending. Manisha (who is known by her given name) turned 20 the day after she scored in Brazil. She said that just being out on the field with one of the best teams in the world was a great experience. “Playing against such a technical side, we had to work really hard on every inch of the pitch,” she said.

Manisha, who hails from Punjab, is a “presence in the dressing room”, according to her teammates. She has also made her presence felt as an attacking threat on the pitch in the past year. Apart from the Brazil match, she scored against Ukraine, the UAE and Bahrain. At a news conference in December, she said that the team has worked really hard on the physical aspect. “In terms of physicality, we were able to compete with them (the South American teams),” she said. She also echoed Dennerby’s views on the team’s speed, which is possibly because it has players, including Manisha, who were into athletics before turning to football.

The physicality of opponents was never likely to faze this group of Indian women—they grew up playing against boys on rugged grounds. But, in order to play high-level football, strength and conditioning training is key. Dennerby, 62, a vastly experienced coach, who was in charge of the Swedish national women’s team—a global powerhouse—for seven years, knows this all too well. He brought in former Swedish international Jane Tornqvist as India’s strength and conditioning coach.

Tornqvist, a tough-tackling centre-back who made over 100 appearances for Sweden, including at two World Cups, played under Dennerby at both international and club-level. She told the All India Football Federation (AIFF) website that the most important thing was that the players had started to get to know their own bodies. “Your body is a tool, and you need to take good care of it in order to perform,” she said. The 46-year-old said that she had not expected to be working in India, but she is settling in well and says that she had always been intrigued by India because of her love for yoga. Recently, she has taken a great liking to dosas. “They are my favourite Indian food now,” she said.

But, talking about favourite food might be a painful subject for the players—they are on a strict diet. Manisha, whose favourite food items are aloo paratha, samosa and pakora, said that she would have been a more advanced football player now had she learned about proper diet four or five years ago and believes that if this information is passed on to younger players, they will advance further. Team captain Loitongbam Ashalata Devi said the diet regimen has had a big positive impact on the team, both mentally and physically.

While the lack of information about diet and nutrition is one factor which has held back Indian footballers in the past, the biggest challenge is the absence of a strong domestic structure in India. However, Ashalata Devi, 28, said it has not been a big disadvantage. “I think our ranking and performances in recent matches speak for themselves,” she told THE WEEK. “Our domestic league is relatively new and it has improved with every edition. Also, a number of our national team players have come from the Hero Indian Women’s League. Yes, there is room for improvement, but we should not be so quick to dismiss it.”

Indian football legend Oinam Bembem Devi has spoken about the financial plight of professional players. She asked corporates to step up and sponsor more competitions to help women get more exposure and earn more. However, Bembem Devi, 41, the first woman footballer to be conferred the Padma Shri, added that the landscape of women’s football had changed a lot since her playing days. “In our times, we did not have branded kits,” she said. “We travelled by bus or train, not by air. We did not have many friendly matches. So, a lot of changes have happened, thanks to the AIFF.”

Apart from the challenges related to the profession of football, living in a patriarchal society also puts an additional burden on female sportspersons. “Men have to improve, and women have to prove themselves,” said Manisha. “This is something that most of my teammates have had to face, too. I have had my brushes with neighbours and relatives who could not see the merit of a girl playing football, but my parents backed me to the hilt, and that is what mattered. Now that I play for the national team, they (neighbours and relatives) have all changed their minds.”

Renu said that she realised that girls can also play football only after she started going to the ground with her brothers. She said that growing up in Haryana was not easy, but added that her parents—both daily wage labourers—were extremely supportive. “Not everyone in society agreed with a girl playing football,” said Renu. “As I come from a very humble family, it was not always easy for my parents to support me. But I am thankful to them, as they have done everything possible to help me keep playing.”

Goalkeeper Aditi Chauhan, 29, who spent two seasons at Premier League club West Ham United’s women’s team, said her parents were not initially supportive. “We did not know any girl who played football to a certain level and for my parents, there was the concern that I would get hurt,” said Chauhan. “There was also the aspect of facing society. My mom was worried about me getting a tan.” The turning point, she said, was when she got her first India jersey. “As my dad served in the CRPF, when I got the India jersey [they understood],” she said.

About the experience of playing in England, she said the biggest difference was that there was an ecosystem where you could find a team, at various levels, and play regularly. “I think the organisation of the Hero IWL has helped us take necessary steps, but there is a long way to go,” she said. “If women start playing matches on a regular basis, we can go a long way. The level of physicality, intensity and tactical awareness that you need in senior international football is immense. We expect more clubs to be a part of the holistic growth of women’s football in the country.”

Though the competition is being hosted by India, the Omicron variant of Covid-19 is likely to mean that the team does not benefit from the support of home crowds. But, defender Dalima Chibber, 24, said that whether crowds are allowed in the stadiums or not, the team knows that the people of India will be “backing their Blue Tigresses from wherever they are”. She said, “And we are going to fight for them and give it our best shot.”

About India’s chances in the tournament, Dennerby said that you cannot think too far ahead. “If you think of the third match before the first, you are in trouble,” he said. “But, I think we can make the quarterfinals, and one added advantage of doing that is that we could get a chance to qualify for the World Cup through playoffs.” India can qualify for the quarterfinals by finishing first or second in the group or by being one of the two best third-placed teams across the three groups.