Eleven blokes walk into a nightclub. Two of them, presumably drunk, rip their shirts off and do the haka—the Maori ceremonial war dance. The manager of the club politely asks them to put their shirts back on as it violates club rules. A commotion ensues and the group is eventually escorted out by bouncers. Another brawl arises outside, punches are thrown and before the fight escalates any further, the 11 men are bundled into cars by security guards and driven away to safety.

The unruly 11 were members of the New Zealand cricket team at the 2003 ICC World Cup in Africa. The team had an unforeseen off-day in Durban, South Africa, as New Zealand Cricket (NZC) refused to let the teams go to Kenya for a group match, because of a bomb blast in Mombasa a couple of days before the match. The Kiwis, led by captain Stephen Fleming, hit the town, before landing in Tiger Tiger club. Young wicketkeeper Brendon McCullum and veteran all-rounder Chris Cairns were the rowdy shirtless duo that brought blushes to the tiny island nation.

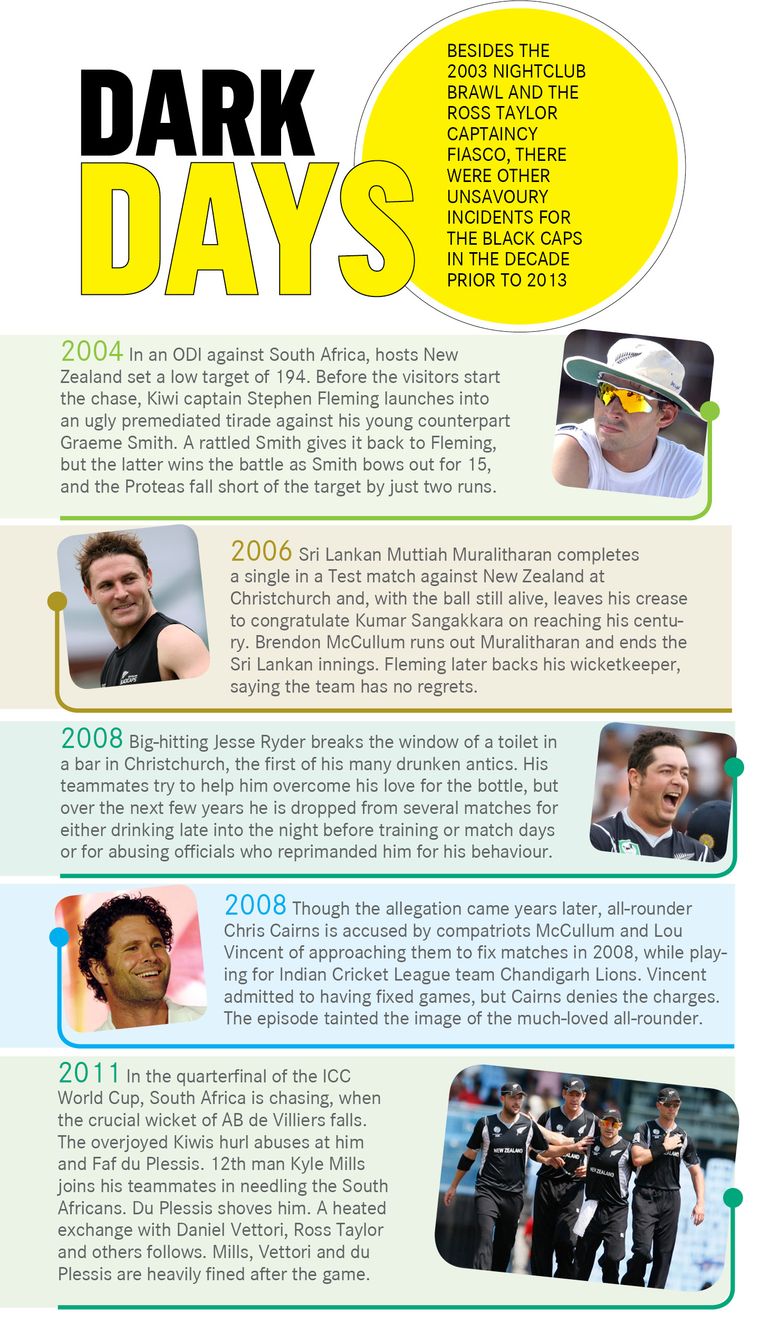

That was the New Zealand side of the noughties. Unruly, aggressive and scorned by opponents, the players were even accused of unsporting conduct on the field (see snippets).

Though worse days were in the offing, the 2003 incident was a particularly low point for a team whose only significant international achievement was winning the 2000 ICC KnockOut Trophy. From the land of the highly successful and respected All Blacks rugby side, these cricketers were like clanging empty vessels.

Eighteen years down, two other men would walk up to each other on a cricket pitch and share a warm embrace under the Hampshire sun after seeing their team through a memorable victory. Ross Taylor and Kane Williamson, the two batting mainstays of the 2010s New Zealand team, had calmly put the finishing touches to help their side win the inaugural ICC World Test Championship final against India. No more the underdog, no more the aggressor, the 2021 New Zealand side is the toast of the cricket world. The good guys, the humble winners, the ambassadors of the gentleman’s game.

It was fitting that Taylor and Williamson were out in the middle to cap off a nearly decade-long process. Because if it was the controversial removal of Taylor from the captaincy that plunged New Zealand cricket into the abyss in 2012, it was Williamson’s leadership that completed the revival.

The change—from being brash and erratic, to becoming large-hearted and consistent—literally happened overnight, 10 years after the 2003 debacle. “What does it mean to play like Kiwis?” was the question hanging in the air as McCullum and members of the team staff sat in his hotel room on the night of January 2, 2013. It was the end of the first day’s play in McCullum’s first Test as captain, and the team had been bundled out for 45, New Zealand’s third-lowest total ever. McCullum and head coach Mike Hesson accepted the fact that the team had long battled an identity crisis and no longer represented the nature of their folks back home.

The decision was to channel this aggression in behaviour into an aggression in their game. Moulded in McCullum’s image, the squad turned into a band of big-hitting entertainers. But more importantly, they also became the nice guys of cricket, on and off the pitch.

McCullum took New Zealand to its first ODI World Cup final in 2015, and Williamson repeated that feat in 2019 before captaining the side to become the sport’s first Test champion. Ranked eighth, eighth and ninth in Tests, ODIs and T20s in 2012, today the Black Caps are ranked first, first and third respectively.

More than their talent, it was the collective spirit of this group of players that got them to the top. As the Kiwis started playing their natural game, rather than mimicking the aggression of rivals Australia, a new breed of cricketers emerged—players with with equal measures of passion and commitment. They were encouraged to be gentler, better sportsmen, reflecting the values of their people and giving rise to a new team culture.

Taylor, who was humiliatingly ejected from the top job in 2012, returned to the team a few months later and got down to working with the new captain and Hesson, who had removed him from the post. On his return, he swallowed his pride, described his relationship with Hesson as a “work in progress” and continued to be a team player. Taylor’s seniority and reading of the game was of much use to McCullum and his successor, Williamson. It was an example to the youngsters that Taylor was committed to the cause of a resurgent side.

A core group of players have been involved in this run. New Zealand has fielded just 35 players in 60 Tests since 2014. This is the lowest among all teams. In comparison, 45 players have played for India in that period, while Australia has had 46 players and England, 59. There was stability, but it did not obstruct the entry of promising new faces. The two standout performers for New Zealand in the WTC final, Kyle Jamieson and Devon Conway, were only seven and two Tests old ahead of the match.

The mix of players in the current squad is being called the best in the nation's history. None other than fast bowler Richard Hadlee himself had pronounced that verdict after the WTC final. The New Zealand dream team of the 1980s, of which Hadlee was the biggest star, has long been considered the greatest. After all, the 1985 squad is the only one to record a Test series victory in Australia.

It was during that three-match series that Hadlee took a staggering 33 wickets. While Hadlee tore through the Australian batting lineup at the Gabba for a haul of 9 for 52 in the first innings, Martin Crowe helped himself to an elegant knock of 188, the combined effort of the two legends scripting a famous innings victory. Other stars in the team included Hadlee’s bowling partner Ewen Chatfield, opener-turned-coach John Wright and wicketkeeper Ian Smith. But statistics back Hadlee’s opinion on the current side.

While it is true that the current fast bowling trio of Trent Boult, Tim Southee and Neil Wagner cannot hold a candle to Hadlee, the three of them have impressive numbers to form the strongest pace combination in New Zealand history. With bowling averages of 25.92 (Wagner), 27.16 (Southee) and 27.84 (Boult), the three of them are among the top five New Zealand bowlers with the best averages to have bowled in at least 40 innings. The other two are Hadlee (22.29) and late 1960s star Bruce Taylor (26.6).

As for the batsmen, Williamson and Taylor will walk into anybody’s New Zealand all-time XI. Opener Tom Latham has made a strong case for himself as he sits seventh on the all-time list of Kiwi run-scorers (4,736 runs) with an average of 41.18. Middle-order batsman Henry Nicholls, too, has been consistent with the bat, averaging 42.52 in his 40 Tests. The four of them figure in the top 10 New Zealand batsmen with the best average to have batted in at least 40 innings.

The now-retired wicketkeeper B.J. Watling holds the record for most fielding dismissals ever (318) by a New Zealander and has on average the best dismissals per innings, too (1.95). The spin department has been New Zealand’s only area of worry, but the country has rarely had world-class spin bowlers barring the likes of Daniel Vettori and John Bracewell, another member of the 1980s club.

The team’s post-2013 revival was masterminded by Hesson, who had the worst possible start to a coaching stint. Hesson was a relatively unknown figure when he took over the coaching position in 2012, replacing the much-loved John Wright. It was a time when cricket in New Zealand was fast losing its popularity, owing to a string of bad results. And here was a 38-year-old coach who had never played first-class cricket.

Over the first year, Hesson took a lot of dirt, literally and figuratively, from the fans. They hurled abuses at Hesson and even left faeces at the front door of his house for stripping the likeable Taylor of captaincy for “not being a good-enough leader”. Hesson has often spoken of how it was the most difficult period in his career, and admitted that he could have handled the situation better.

Taylor and Hesson eventually patched up. Over the following years, Hesson’s players would heap compliments on him for different qualities: for being “superbly organised”, an “intricate planner”, a “solid man manager”, and for having a “sound cricket brain”. Wright added to the praise, too, when in 2015 he told ESPNcricinfo: “There is a preconception that it helps to have played to coach, but it is not completely necessary. If you have not played you need to be able to look, learn, watch and absorb—Mike's got those qualities.”

The New Zealand cricket authorities, meanwhile, backed the team making use of limited resources. They gradually improved facilities across the small nation and relaid several pitches with Patumahoe soil to provide more pace and bounce to the slow, seaming pitches. Of the two clay soils available in New Zealand, Patumahoe dries quicker, tends to get flatter over the first three days of a Test, and does not usually break up in the last two days. The pacers took advantage of this and harassed visiting batsmen.

But the board continues to bleed money, with very few series returning a profit. The gap in resources between New Zealand and the Big Three of world cricket made the Test championship victory even more impressive. According to NZC’s 2019-20 Annual Report, the association earned a total revenue of NZD$66.6 million (Rs317 crore) during the financial year. This amount is dwarfed by the Rs3,730 crore that the BCCI made in the same period.

Despite all of this, there has been criticism and scepticism, too, of whether their WTC win accurately represents a dominance. For one, since the start of 2017, 10 of the 14 Test series that New Zealand played were on home soil. The away series included a 0-3 drubbing in Australia.

Moreover, the team is lucky to have had to deal with few injuries to their first-choice players. Unlike India, which has 608 players to choose from 38 domestic teams, New Zealand has just 96 players to choose from their six local teams.

On an episode of Sky Sports Cricket Podcast last year, Kiwi veterans Simon Doull and Ian Smith shared their worries about the team’s future. “My concern is where is our next batting talent?” said Doull. “Watching first-class cricket, I don’t see a lot of it. I see a lot of bowling talent coming through and I don’t think we have many issues there. But I worry about where our next batting talent is coming from.” He went on to talk about the need to expose more players to international cricket, starting with T20 internationals.

When asked about the state of domestic cricket, Smith sounded despondent. “It does not get me too excited,” he said. “[Domestic cricket] just drifts along. There is absolutely no public interest, and no one goes to watch games. Probably 80 guys play first-class cricket, and of that I’d be dreaming to say 20 of them are capable of playing Test cricket. Somehow, we have to identify the talent much earlier.”

The two new entrants who have flourished, Jamieson and Conway, are late bloomers at 26 and 29. The six-foot-eight Jamieson caught the attention of national selectors when he picked up 22 wickets in the 2018-19 Super Smash T20 league in New Zealand. He was man of the match on his ODI debut against India in 2020. He would make his Test debut, too, against India, and now has five five-wicket hauls from his eight Tests.

Conway, originally from South Africa, moved to New Zealand in 2017, and was the leading run scorer of the 2018-19 season of the Super Smash tournament and the 2018-19 and 2019-20 seasons of Plunkett Shield, the domestic first-class tournament. Conway made his Test debut against England in May and already has a century and two fifties to his name in just three Tests.

Late debutants like them seem to be the norm rather than the exception. Eleven out of the 12 players to earn their first Test caps since 2016 are 25 or older, with the median age being 28. In comparison, the current backbone of the team comprising of Latham, Williamson, Taylor, Boult and Southee all made their debuts at 23 or younger.

Williamson, particularly, rose through the ranks quickly and emerged on the global stage as a fresh-faced 20-year-old. His contribution to the team cannot be quantified by just the numbers, though they are far greater than any batsman the country has ever produced. He is the modern-day Mr Cricket, exuding calmness, simplicity and, most importantly, sportsmanship.

For all the obvious differences between the New Zealand captain and his Indian counterpart Virat Kohli, there are similarities, too, that are rarely discussed—the elegance in their batting strokes, the steely resolve and focus at the crease and their ability to rally their respective troops. Another similarity is how the two have tried their best to lead fiercely private lives.

Though Kohli has been forced to do so in recent times—to protect his family from frenzied fans and paparazzi—Williamson has always been a reticent character. When he and his partner, Sarah Raheem, had their first child in December 2020, there was little fanfare around it, compared with the birth of Kohli’s daughter just a month later. Maybe that says more about the fan culture in the two nations, but it also reflects their public personas. There is little that the public knows about Raheem, a nurse he met during medical treatment, though they have been dating for over five years.

In 2015, McCullum cleared doubts whether Williamson’s introversion would affect his prospects as a leader. “Kane is passionate, but he is level with his emotions,” the former skipper told ESPNcricinfo. “At times, he can be a little bit mistaken for not being passionate or caring—he just gets in his zone. But you don't fight that hard unless you care about something. He does have blood in his veins.” Be it blood or ice in his veins, Williamson has led New Zealand from the front.

The WTC final that he won was not only expected to be a celebration of cricket’s longest and most cherished format, but also the culmination of the first Test championship season conceived to revive the waning interest in the format. Despite two days being washed out and low scores in all four innings, the last two days provided enough to keep fans hooked. Not just because there was plenty of action, but because David was taking on, and defeating, Goliath.

The nice guys won, and their redemption arc has been captivating. Where this nation goes from here depends on the domestic system's ability to churn out players consistently. But having got this monkey off their back—after two consecutive failed World Cup finals and six previous semifinals—at least they are no longer cricket’s eternal bridesmaid.