I first met the German football legend Lothar Matthäus last December. I had seen him before that. On television, in 1986, when Diego Maradona conjured up unforgettable goals and assists at the World Cup in Mexico. Matthäus was part of the West German team which had stalwarts such as Rudi Völler and Karl-Heinz Rummenigge. Yet, he was the one who scored against Morocco in the pre-quarters. And, in the final against Maradona’s Argentina at the Azteca, coach Franz Beckenbauer entrusted him with the task of reining in the man who stood between them and the cup. He stopped Maradona from scoring, but could not stop the winning pass from the great man as his team went down 2-3.

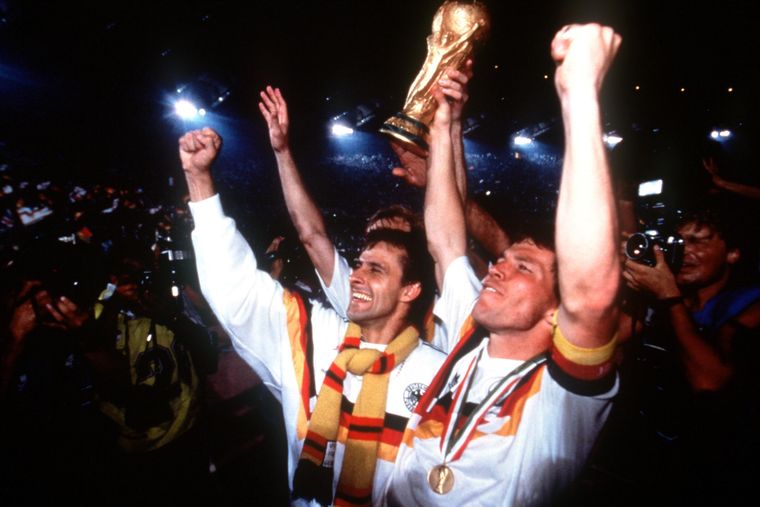

Two years later, Matthäus, veteran of two World Cups by then, led West Germany to the Euro Championship semi-finals. He became a World Cup-winning captain in Italy 1990. East and West Germanys became one the same year, and Matthäus played two more World Cups for unified Germany. He was the first recipient of the FIFA World Player of the Year award, in 1990, and remains the only German to have won it. Moreover, his participation in five World Cups is a record he shares with Mexico’s Antonio Carbajal and Rafael Márquez.

Yet, Matthäus was not my hero. Nor Germany my favourite team. I am sure many Indian fans of my generation shared my lack of admiration for the robotic Germans. I favoured Brazil and Argentina, who had players with dancing legs and the ability to glide into the penalty box with such ease. Players who made commentators stretch their vocal cords and yell, “Goooooooaaaaal!” Holland, Portugal, France, Croatia and even Italy to an extent became the teams I wanted to watch over and over again, but Germany remained an academic interest. I would put part of the blame for that on former German coach Berti Vogts, who, in a moment of exasperation in 1998, said that when compared with the Brazilians, his players “dance like refrigerators”.

The epithet dancing refrigerators made way for dancing robots in 2014, as the Germans destroyed the Canaries on the way to their World Cup triumph in Brazil. The first round exit in Russia 2018 was attributed to the unimaginative style of play born out of the obsession for perfection. In the football incubators of Germany, every single detail of budding players are documented, analysed. The data gets piled up over the growing years, and by the time he is ready for the country, nearly all his flaws would have been eliminated, and he would be fully programmed thanks to hours of precision training. But are the Germans forgetting that the great game does not always follow the script?

It is with these misgivings that I met Matthäus and sat down for a brief interaction, at the end of which he invited me over to Germany. The visit provided me with an insight into the German football world. Nearly all the coaches and organisers I met argued that they do not groom players to be robots, but better professionals.

The change in training, most experts said, was a result of the first round exit of defending champions Germany from the Euro Championships in 2000. Till then, they were led by the prophecy Beckenbauer had made in 1990. With the inclusion of the East German players, he had said, Germany would become unbeatable in the years to come. It held true exactly for a decade. Euro 2000 was a real shocker for Germany, and forced the establishment to have a relook at the coaching system.

The average age of the Euro 2000 squad was 31.5—clearly an ageing side. Former German striker Oliver Bierhoff ripped into the football system in the country, saying the technique of players needed to improve and German football desperately needed a rebirth. The German Football Association (DFB) went into a huddle following Bierhoff’s comment, to discuss a new roadmap.

Professional coaches were sent to the villages and sleepy towns during weekends and holidays, and they met with amateur coaches who were still high on the glorious past of German football. For the children who were being trained by the amateurs, football was by no means a way of life or a prospective career, but an interlude to break the monotony of life. That began to change with the advent of the ‘mobile’ coaches.

In 2002, a multimillion project was initiated to improve the standards of football, and every club and academy was brought under it. The project resulted in the addition of 1,300 German pro-licence coaches, 366 football centres and 54 high-performance hubs, many of them residential facilities.

Since then, the DFB has spent about €130million every year to run the high-performance hubs. Manuel Neuer and Mesut Özil are products of FC Schalke 04’s boarding school, while others like Marco Reus, Leroy Sané and Jérôme Boateng were at similar schools run by other clubs. Germany won four youth Euro titles in six years, starting with the 2009 Under-21 Euro, which had the first batch of players from the project. These players later formed the core of the team that won the 2014 World Cup.

The project was based on the concept of FC Barcelona’s La Masia academy, albeit on a much larger scale. The DFB had also invested €100 million in a DFB academy in Frankfurt, headed by Bierhoff. His dream is to make the academy a football city in itself. England started its St. George’s Park National Football Centre in 2012 on similar lines, which also helped the country win a string of international youth tournaments and reach the semifinals of the 2018 World Cup.

Politics, music, the arts and football are integral parts of German culture. The 2000 meltdown suddenly put the focus on football. If you compare Germany with other European countries, you would find that the Germans prefer stability over change, even in politics. They are immensely proud of their legacy in football. This does not mean that they are not open to change. In fact, they do not mind tinkering with the system as long as the game is not commercialised. So when changes were introduced post 2000, they were worried that the basic nature of their football culture would be commercialised, and that that change will hit their favourite clubs. To understand this fear, we should first know the ownership structure of German clubs. It is based on the 50+1 formula—the fans hold a minimum of 50 per cent of the shares plus one share. (Read ‘Possession play’ on page 94.)

The fans finally came to peace with the fact that German football, as they knew it, was dead and buried. They had no choice but to nurture the saplings that grew from that grave.

At this juncture, it would be prudent to examine what happened to Beckenbauer’s big dream. After the fall of the Berlin Wall, the two teams became one, but not many from the erstwhile East Germany could make it to the national team. Many talented players from the east migrated to the celebrated clubs of the west, thanks to better pay and living standards. But the fact is that football in the east and the west is still at two different plateaus. The only player from the east to make it big is Toni Kroos. But then, he is a Bayern Munich product, thanks to the far-sightedness of his football-coach father Roland Kroos. Toni Kroos is currently with Real Madrid, and is an integral part of the national team. In a way, he is a product of capitalism, plucked out from an erstwhile socialist country.

But Germany’s football system is not entirely capitalist, when you compare it with the rest of Europe. Suffice to say that Germany developed an ‘Autobahn’ in football as well. German highways have strict rules. In football, too, Germans believe in strict adherence to the total plan. German football places emphasis on three points: finance, sports and society. Of these, society is of paramount importance, the leading characteristic of which is adherence to tradition.

“Football starts with the fans,” said Christian Seifert, CEO of Bundesliga, the German football league. “They are the ones who come to the stadia. They are the ones who watch the game on television. They are the ones who bring in the money. And it is that money that gets invested in the game. When people enjoy the game, the sponsors cannot stay away for long.”

The Bundesliga has fans across the globe. But, even though other top leagues are looking to host matches outside their home country, the Bundesliga has stayed put in Germany. Why? Especially when it helps expand the fan base and the reach of the league? Seifert has the answer: “We are certainly grateful to our fans from other countries. But how can we disappoint our fans in Germany who have been supporting the league for decades? They may not be keen to attend matches played outside the country. At the moment, we are not even considering taking the Bundesliga out of Germany.”

For most people outside Germany, the Bundesliga represents only the first division which involves top teams like Bayern Munich and Borussia Dortmund. Not many know about the equally popular second division, which, on an average, commands an attendance of 21,000 per game. Compared to this this, the Italian first division, Serie A, has an attendance of 23,000 per game. The German second division is the seventh biggest league in Europe.

The common notion is that viewership is directly proportional to earnings. But Bundesliga officials insisted that they work hard for every euro. Commercialisation in excess, they said, will destroy the fragile football ecosystem. And youth development programmes initiated after the 2000 debacle are protecting that ecosystem.

Money may not be everything, but money is important for the sustenance of the league. Last year, the Bundesliga’s earnings grew by 13 per cent to €31.81 billion. It paid €1.28 billion euros to the exchequer and provided direct employment to 55,000 people. Even the famed German automobile industry struggled in the economic slowdown of 2018, but not the football league. Bundesliga officials hoped that globalisation of the game and digitalisation of the telecast would further augment the earnings, even as the league stays immune to global franchises and commercialisation.

A study of 51 leagues in 42 countries from 2013 to 2018 revealed that on an average, the Bundesliga commanded 43,302 attendance every match. The corresponding number of the second-placed English Premier League is 36,675. Spanish La Liga came third with 27,281.

And, the popularity is directly proportional to the number of goals scored. Statistics of the last three decades show that the goal average per Bundesliga match is 3.1. Come to Germany for a goal fest, seems to be the league’s clarion call. The match ticket for a chair in Bundesliga costs a minimum of €26. For a place on the terrace, where you can watch the match standing, you have to pay as little as €11. Food and beverages inside the stadium are moderately priced. An EPL ticket will set you back by a minimum of €36.

The Bundesliga is also known for giving more first-team chances to youngsters, both local and foreign. Christian Pulisic, Jadon Sancho and Weston McKennie are some foreigners who found their wings in the Bundesliga as teenagers. Between 2009 and 2017, the average age of players in the Bundesliga was 25.84. In France it was 25.91; Spain, 26.5; England, 26.79; and Italy, 27.13.

Watching a Bundesliga match is not complete without taking part in the allied activities around the stadium. The authorities provide a total sporting experience, with opportunity to take part in handball, volleyball, basketball, tennis, hockey, ice hockey and even boxing. Most places offer a gym and swimming pool as well, for its members. Training facilities are also available on demand.

But it is football that wins the day; it is football that makes it possible.