On a hot summer’s day in Mumbai on April 10, 1979, while I was cooling myself in the shower after a match at the Cricket Club of India, I heard the baritone of the famous cricket connoisseur Rajsingh Dungarpur. He came shouting, “Where is Sunny?” A feeble response from me had the giant six-footer CCI president opening the shower curtain with words of “Congratulations, my boy! You have been selected for the World Cup.” Before I could absorb the news and react, he hugged me with not a care about the running water from the shower or the naked me. The two wet Rajput princes in such a posture would have created a frenzy on today’s social media.

I, personally, had not expected to be selected and, hence, the news, apart from the humorous way in which it was conveyed to me, made me think of the reality of my dream of playing cricket for India in the World Cup. This is something a cricketer aspires for, as the World Cup has that exclusive and elite ring to it.

The Board of Control for Cricket in India was then not flush with funds, and so we received some ill-fitting suits, blazers and cricket clothing. A half-sleeve and a full-sleeve acrylic sweater and white cricket flannels were what the BCCI believed would be sufficient to withstand the cold and wet weather of England. Watching us shiver during a match, the famous woollen brand Lyle and Scott was kind enough to provide us with sweaters of the Indian colours. A wonderful gesture or else at least half of the side would have been back in India suffering from pneumonia. The famous Madras flannels, after the first wash, had shrunk to a size that had left the great G.R. Viswanath, the shortest of the team, with ample choice.

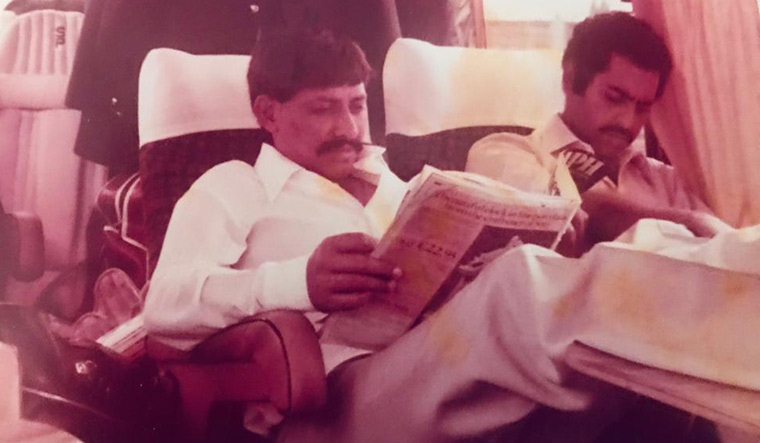

These trivialities were of little concern for cricketers in those days, as to be a part of the Indian side was all that mattered. There was that buzz when we sat waiting for our flight to London. Sunil Gavaskar was not one to sit idle. He got a few of us to explore the duty-free shops and we decided to treat ourselves to a cold drink. We did quench our thirst most heartily only to choke when we were asked to pay the amount in foreign exchange. The Indian regulations did not permit the supplier to accept Indian rupees, and, as we were still to receive our foreign exchange, none of us had the money to pay. Gavaskar’s fame, we thought, would be our trump card but an agitated Indian vendor was just not inclined to forgo the money as a goodwill gesture. We were finally rescued by a nice Indian individual. This was the beginning of a journey that may not have brought laurels on the cricket field but plenty of fun off it.

One does feel royal at the immigration when one is treated to a nice waiting room with the passport being stamped without one standing in the queue and going through a series of questions. We were received by the famous former England captain Ted Dexter. I had been an admirer of his and had many of his pictures in my scrapbook. Yashpal Sharma had no idea about the great cricketer and so very conveniently handed him his handbag to carry. I defused the situation by informing Yashpal in Hindi and, like his batting, he adapted to the situation perfectly well and quietly retracted the bag from the legendary cricketer.

We were then put into a coach, driven to a nearby hotel to freshen up and thereafter taken on a long and tedious drive to the northern part of the country—to Scarborough in Yorkshire.

The cold, wet and dreary weather up north made it the most inappropriate venue as a preparation for the World Cup. The English cricket board must have not thought much of the two leading Asian teams, as both Pakistan and we were left to play amongst each other, with no thought or care at all about our relationship.

The five days of interaction with the Pakistan cricketers was the most enjoyable part of our World Cup journey in 1979. The rain and wet conditions made it impossible for us to play outdoor cricket, and indoor practice was all that both the teams managed. Although, Imran Khan was not the captain, he was the superstar of their side. The tall, strapping, good-looking Pathan had a physique to die for, and strutting around in his briefs, he would make his way to our dressing room. He would then walk over to meet Gavaskar and some of the other senior members of the team. He would flex his muscles and pretend he was loosening them. A great way to psyche us, and with Gavaskar imitating him after his departure, the dressing room was in splits.

We did manage to play a friendly match one sunny afternoon, although the wicket was not conducive for fast bowlers to operate in. S. Venkataraghavan, our captain, gave me the ball to bowl off spinners to the young and talented Javed Miandad. Bowling to him, I realised how good he was and how late he played the ball. A sweep from outside the off stump to the fence and then a reverse sweep that we saw for the first time from a ball pitching outside the leg stump had my captain writhe with anger. Today, this has become a common way of sweeping a spinner but during that time it was a humorous incident for your teammates to laugh about and make fun of.

The person I got along well with was Wasim Raja from the Pakistan team. He was stylish, handsome and played his cricket with flair and confidence.

Our weekly allowance to pay for our meals, laundry and incidental expenses was just £105. Wasim considered himself an astute gambler and had, as he quite confidently told me, mastered the way of making money at blackjack. His explanation had a good reasoning for me to accompany him to the casino to make a bit of extra pocket money. Like a bad penny I was back, having lost my entire kitty. Penniless for the week, I relayed my predicament to my roomie Gavaskar. He had a laugh but suddenly realised that he would have to look after me till we got our next allowance. A man of precision, the legendary opening batsman kept a thorough account of my borrowing. A tale of “not a penny more, not a penny less”.

England, with its tradition and history of the game of cricket, does bring about an atmosphere that is very difficult to replicate elsewhere. The next important function for us was the banquet at Buckingham Palace. All the participating teams were invited to meet the Queen, Prince Charles and Princess Anne. We were briefed about the etiquette and the way we had to shake hands and reply only when spoken to by her majesty. One has to marvel at her tenacity to meet and greet each member individually with a smile and welcome that made one feel special.

The moment to savour was the lunch and photograph session that took place at Lord’s thereafter. The famous cricket photographer Patrick Eagar had us all lined up on the hallowed turf of Lord’s, facing the pavilion. To be a part of that historical photograph, and the interaction with fellow cricketers, made one feel like one had finally achieved a place in the world as a cricketer. The mingling with players from the West Indies, England, Australia, New Zealand, Pakistan, Sri Lanka and Canada was truly something special.

London is a city that is vibrant and full of life, but the hotel rooms are really dingy. A double room is barely adequate for two individuals and with our cricket coffins and suitcases, we were jumping over furniture and bags to move around the room. The problem that one faced was lugging our trunk to our rooms, as the hotels where we were staying had no porter service. The only redeeming feature was, every room had one welcome Kitkat chocolate and the one who reached it earlier—Gavaskar or I—claimed it as his trophy. We finally had to make a pact to share it, as we realised that the World Cup was only the start of a three-and-a-half month tour of England.

Cricket was finally on our agenda. We travelled to Birmingham to play our opening match against the strong West Indian side at Edgbaston. On the measly amount that we were given as allowances, the news of a dinner with BCCI president N.K.P. Salve and some of its members on the eve of the match was very welcoming. A few inspirational speeches and thereafter, plenty of food was a treat for each one of us. We were playing the next day and so excused ourselves early to see the board administrators enjoying themselves and in good spirits.

Later, in the week when we were given our week’s allowance, I questioned why we were given 18 pounds less. The explanation was quite simple and hilarious: “This was the cricketers’ contribution to the BCCI president’s and members’ dinner”. The phrase “there is no such thing as a free lunch” seemed so appropriate to the way in which the cricketers were treated back then.

The West Indian bowling in our first match did prove to be difficult for our batsmen to handle. Viswanath, however was an exception. His innings of 75 runs was one of the finest that one was privileged to witness. On a fast green-top wicket against [Michael] Holding, [Andy] Roberts, [Joel] Garner and [Colin] Croft, the short and stocky Viswanath was flicking and cutting the express bowlers with ease and grace. This was the first time that some of us saw the bowler who was later christened as the Whispering Death—Holding. His run-up to the wicket was so smooth and fast and with an effortless action, the ball whizzing past the batsmen like never seen before. Being the 12th man, I had been given a handycam to film the lean and mean West Indian bowler. I do not think that my camera skills were adequate enough for any of us from the Indian team to decipher Holding’s variations and skills.

India was still to learn the way to play the limited overs format. The 60 overs, without any field restriction, brought about confusion as to how to approach the innings. Some felt a solid defensive start playing through the first 30 overs without losing many wickets would give a good base for the later batsmen. This was how Gavaskar, Anshuman Gaekwad, Dilip Vengsarkar, Viswanath, Brijesh Patel and Mohinder Amarnath approached the second match against New Zealand. The outcome proved disastrous and we could not accelerate later and totalled only 182 runs that the Kiwis easily chased.

The two defeats put India out of the knockout stage and our last match was against minnows Sri Lanka, the still-to-play Test match team.

I felt this was a good time to have a one-on-one with our captain Venkataraghavan. I asked him if I could play the last match against Sri Lanka, after all we were out of the tournament. He decided not to make a change, and India faced the embarrassment and ignominy of losing to Sri Lanka as well.

Angered and disappointed at watching India collapse, I switched the channel for us to watch our tennis star Vijay Amritraj taking a two-set lead and leading 4-1 in the fourth set against the mighty Bjorn Borg. The short-tempered Indian captain at this juncture switched off the television and we learnt later that Amritraj finally lost in the fifth set. We understood his disappointment as we trudged away from the Old Trafford dressing room, feeling equally low and depressed.

We did go and watch the World Cup final at Lord’s where the brilliant century of Viv Richards and the equally good bowling of Joel Garner demolished England. We cheered the winners. Maybe the humiliating defeat of the 1979 World Cup was what ignited the fire in the belly of Kapil Dev’s 1983 winning side, when India finally got to lift the Prudential World Cup Trophy for the first time.