March 19, 1514; morning: João de Faria, Portugal’s envoy to the Holy See—the central governing body of the Catholic Church—toiled feverishly over an extraordinary task. Before Rome awoke, the jurisconsult supervised the grooming of an Indian white elephant, an “exotic” marvel meant to match the imaginations of Pope Leo X. The four-year-old animal, having endured a gruelling journey from “Cochim” (Kochi) in distant India, was bathed in fragrant waters, its majestic form draped in resplendent caparisons. De Faria ensured no trace of exhaustion betrayed the elephant’s grand arrival. Everything had to be perfect.

De Faria was part of a Portuguese mission on its way to meet the pope; the colonial power wanted his blessings for its expansion plans. The entourage represented King Manuel I, under whose reign Vasco da Gama made the invaluable discovery of the sea route to India. Manuel had chosen the most unusual exotic birds and animals—parrots, parakeets, rare dogs, Indian fowl—from his royal menagerie as a gift for the pope. But the crown jewel was the Indian white elephant. Elephants had not graced the streets of Rome since the era of the Roman Caesars, so the Eternal City buzzed with excitement as the Portuguese delegation began its procession.

As they neared the bridge to Castel Sant’Angelo, a Roman-era fortress used by the popes, cannons were fired in their welcome. As he suffered from myopia and presbyopia, Pope Leo X used a “sighting tube” to watch the parade. When the elephant neared the tower, it paused, knelt and bowed its head in reverence. The pope laughed like a child. What followed amazed him even more: the elephant took in water from a nearby trough with its trunk and sprayed it high enough to drench the pope and his entourage. The Indian elephant, christened Annone by the Romans (or Hanno in its anglicised form), captured the pope’s heart and became his most cherished pet.

Yet, in the next two years, the elephant’s presence would have a far more significant role in medieval European history—and, by extension, world history—than merely serving as a papal companion.

It was not till the 1990s that this remarkable story was brought to light. American historian Silvio A. Bedini began his search based not on a legend he heard about the pope’s elephant, but one about a rhinoceros. However, as he delved into his research, the tale transformed into the story of Annone.

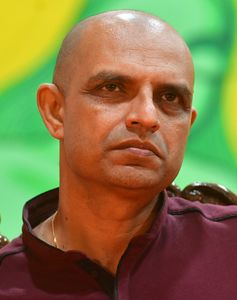

Fast forward to 2024. Two acclaimed writers from Kerala, Benyamin and G.R. Indugopan, embarked on a journey to follow in the footsteps of Annone. Their journey began in Kochi, taking them to Lisbon and then along the same historical path that Annone had travelled centuries earlier.

In November 2023, Indugopan published his novel Aano, a rich, immersive tale set in medieval Europe, in which the white elephant and its Indian mahout take centrestage alongside iconic Renaissance figures like Pope Leo X, Raphael and Leonardo da Vinci. Reflecting on their journey following Bedini’s findings, Indugopan said: “It’s one thing to imagine these places while writing, but witnessing them first hand brought an entirely new perspective.” Benyamin said his passion for blending history and fiction motivated him to join Indugopan. “Additionally, I have always been interested in the migration stories of Malayalis,” he said. “The story of both people and an elephant migrating to Europe as early as the 1500s is truly remarkable.”

ELEPHANTINE TASK

Born on a farm in Connecticut to Italian immigrant parents, Bedini had an early passion for puzzles. At just nine, he won a prize for solving a coded puzzle in a local newspaper, which eventually led him to the US military intelligence. During World War II, he served with MIS-X, a top-secret agency, and by 1945, he was its chief liaison with the Pentagon. However, his military service ended with the war.

Bedini transitioned to history and academia, beginning his prolific writing career in 1958. In 1961, he joined the Smithsonian Institution as a curator in the department of mechanical and civil engineering, playing a key role in founding what is now the National Museum of American History. He also served as deputy director of the museum and was the Smithsonian’s keeper of rare books.

Bedini first heard the legend of a pope owning a rhinoceros at a reception at the American Academy in Rome, shortly after arriving to research in the Vatican library. His initial search, however, led to a dead end. During his second visit to Rome, Bedini received information on citations of two manuscripts related to an elephant from the Vatican library, and soon he figured out that the period he needed to research was the reign of Pope Leo X.

His search extended to the Vatican’s secret archives, the Portuguese Royal archives and various other repositories across Europe, which gradually unveiled to him a unique bond between the pontiff and his Indian pet.

Born in 1510, Annone began its journey from Kochi during the monsoon of 1511. While another elephant, a gift from the Rajah of Kochi to the King of Portugal, shared the voyage, Annone was specially bought by Afonso de Albuquerque, the viceroy of Portuguese India. Albuquerque’s orders, dated January 12 and 19, 1511, detailed the meticulous care provided to the elephant, including specific amounts of rice, butter and oil.

Before retracing Annone’s journey from Lisbon to Rome, Indugopan and Benyamin visited Montemor-o-Novo, a municipality about 100km from Lisbon, in search of a unique fresco. “The 1755 Great Lisbon Earthquake and the fires that followed destroyed much of the city’s heritage, including clues about Annone’s life in Portugal,” said Indugopan. “The fresco in Montemor-o-Novo became one of the few remnants.”

The fresco was in the village church of San Pedro da Ribeira, but to their disappointment, the church—long out of use for religious purposes—was closed. “We then contacted the local authorities with the help of an Indian priest working in Portugal,” he said. “They shared a picture of the fresco with us.”

From Lisbon, the ship carrying Annone sailed along Spain’s southern coast. “The first stop was Alicante, followed by Ibiza, then Palma and finally Porto Ercole,” he added. “We retraced the same path. In Porto Ercole, locals shared faint memories passed down through generations about the elephant that graced their port town 500 years ago.”

Benyamin found this fascinating. “Porto Ercole was merely a temporary stop for the elephant on its way to Rome. Yet, the fact that its story has become part of the town’s legends shows how profoundly it impacted the land at the time.”

After Annone made its memorable entrance into Rome, the pope expressed his delight in personal letters to King Manuel I, saying that the elephant provided “the greatest amusement” and became an “object of extraordinary wonder” for the people of Rome. Pope Leo X commissioned a special enclosure for Annone between Castel Sant’ Angelo and the Apostolic Palace, and often visited to see its antics and intelligence.

The Malayalam word for elephant, aane, used by the Indian mahout to call the animal, eventually led the Romans to adopt the name Annone. Rome was bustling with artists under the pope’s patronage, and Annone became a subject for towering figures such as Raphael and his principal heir Giulio Romano.

According to Bedini, Michelangelo and Da Vinci undoubtedly saw Annone, but the historian could not trace any evidence that they had sketched it. For the next two years, the elephant participated in various papal festivals, processions and spectacles. The pope was particular about conducting extravagant celebrations and his elephant became the highlight of these carnivals.

However, Pope Leo X’s extensive cultural patronage, political manoeuvring and opulence, as well as his theological positions, were laying the groundwork for a profound socio-religious upheaval, with Annone set to become a key victim.

CURSE AND CARE

In May 1516, Fra Bonaventura—a Franciscan monk known for his fiery sermons and prophetic claims—arrived in Rome with his followers. He had announced himself as the “Angelic Pope” whose coming had been foretold.

In front of the Roman populace, he announced that he had excommunicated the pope and all the cardinals, and asked the faithful to dissociate with them. He also made a prophecy that the pope, five cardinals, the pope’s elephant and its mahout would die before September 12, 1516.

Prophecies were greatly respected then and Pope Leo X personally had great enthusiasm for astrology. The pope ordered the arrest of Bonaventura; however, in early June, Annone fell ill. The elephant lay still in its pen and showed great difficulty in breathing. The pope immediately summoned the finest physicians in Rome, including his personal one, and rarely left his elephant’s side. However, no efforts saw success and Annone died on June 8, 1516. The pope became inconsolable.

To immortalise his pet’s memory, the pope commissioned Raphael to create a life-size painting of the elephant at the Vatican’s entrance, insisting Raphael himself do it and not his assistants. The pontiff also composed a fitting epitaph for the elephant, writing, “…in my brutish breast they perceived human feelings; fate envied me my residence in the blessed Latinum…” As Raphael finished the mural, it became one of the earliest European depictions of an elephant to be drawn directly from life. And pilgrims from all over the Catholic world entered their holy city watching this Indian elephant on the Vatican’s gatehouse.

Notably, Annone’s death and the pope’s excessive mourning attracted anger and ridicule from reformists, who were already critical of his plan to sell indulgences—grants by the Church that claim to reduce temporal punishment for sins—to fund the rebuilding of Saint Peter’s Basilica. In fact, the elephant became a topic in one of the first published papal criticisms from German supporters of Martin Luther, who would kickstart the Protestant movement.

Just a year after Annone’s death, Luther would publish his Ninety-five Theses, which condemned both the sale of indulgences and the opulence of the papacy. The theses would become the cornerstone of the Protestant Reformation that led to a split in the Catholic Church and significantly influenced the socio-political and religious landscape of Europe, contributing to far-reaching changes that included the rise of capitalism.

Today, Raphael’s fresco of Annone no longer exists in the Vatican, having been destroyed during a modernisation project. However, the drawing (or possibly a copy) on which the mural was based still survives in the von Beckerath collection at the Kupferstichkabinett in Berlin. At least four major representations of the elephant remain on public display in the Vatican today, though Annone’s story faded into obscurity along with the mural. These depictions went unrecognised until Bedini revived the tale.

Indugopan, however, pointed out discrepancies they observed. “For example, we saw that two elephant tusks with 16th-century copper decorations are displayed as the mortal remains of Annone. Bedini accepted these tusks, [discovered by Vatican archaeologist Margherita Guarducci], as belonging to Annone in his book. But the Pope’s elephant was only seven years old when he died, and could not have had full-grown tusks. Additionally, sketches by artists like Raphael depict the elephant with short tusks.”

EXOTIC INFLUENCERS

In 1516, the year Annone died, English lawyer and humanist Sir Thomas More published his masterpiece Utopia—a fictional work that had a lasting impact on political thought, philosophy and global history. Utopia not only introduced the concept of an “ideal society”, but also reflected the intrigue, corruption and scandals of European society at the time.

Scholars note that Utopia, published at the start of the Reformation era, significantly contributed to the decline of papal supremacy, even though More, ironically, opposed the Protestant reformation and his king Henry VIII’s separation from the Catholic Church. Greek philosophy, Christian theology and interactions with humanist thinkers all influenced More in writing Utopia. However, the book was also inspired by the narrations of Joseph the Indian, an Indian Kathanar (St Thomas Christian priest), who travelled to Europe to seek an audience with the pope. Joseph and his brother Mathias were priests from Kodungalloor, which was home to the ancient port city of Muziris. The duo approached Portuguese navigator Pedro Álvares Cabral and persuaded him to take them to Europe, setting sail on January 10, 1501 (according to a narrative written by an anonymous pilot in Cabral’s fleet). Unfortunately, Mathias died en route, but Joseph reached Lisbon and remained there as a royal guest until January 1502, before travelling to Rome.

During his life in Europe, he gave interviews in Venice, Lisbon and Rome, in which he shared detailed accounts of life in India, Hindu culture, the social system and the indigenous Christians. These interviews were recorded and published in more than a dozen versions in various European languages since 1507. It came to be known as the narratives of Joseph the Indian.

Scholars such as Joseph Minattur and British academic J. Duncan M. Derrett have played a crucial role in uncovering Utopia’s connections to India and Joseph. Derrett notes that More exhibited a distinct preference for the verifiable over the imaginative, and he highlights that More himself attributed the “genius” of Utopia to gymnosophy—the philosophy of ancient Indian ascetic sects who “lived in a commonwealth devoid of lust, pride and greed”.

Furthermore, the protagonist in the book, Hythloday—a well-travelled figure who had visited eastern lands, and possessed extensive knowledge about various foreign countries—could have been inspired from Joesph. Notably, the narratives of Joseph were the only first-hand account from an Indian available to More at that time.

Minattur thinks that the language of Utopia—which is entirely imaginary—borrows certain words from Malayalam, the mother tongue of Joseph. He specifically notes that ‘Agrama’ (translated as “not village”) resembles ‘gramam’, the word for village in Malayalam. Derrett draws comparisons between Utopian religious practices—where public and private worship coexist and a single god is recognised, albeit under different names and rituals—and customs in the Malabar region.

However, just as Annone’s influence on Europe’s Renaissance era faded into obscurity, so, too, did the legacy of Joseph the Indian, until its rediscovery in the 20th century. “When Annone was presented to the pope, the Portuguese ambassador declared he was laying India at the pope’s feet,” said Indugopan. “India mattered because the wealth from India and the east helped Europe build its most magnificent creations. However, the long history of colonialism has led to Indian contributions being overlooked. That’s why revisiting these events through an Indian lens is more crucial than ever.”