Ek failure insaan (a failed person).

That is how Amit Yadav, 33, signed off the last note of his life in the rain-swept wee hours of August 23 in Bhagirathpura, Indore. He had hanged himself next to the bodies of his 30-year-old wife, Tina, three-and-half year old daughter Gyana and one-and-a-half year old son Divyansh aka Timu. All three had died of poisoning.

The discovery of the bodies in the single room tenement had sent shockwaves in the congested, old locality where Tina had grown up.

Tina’s parents, who live 100m away, are inconsolable. “What hurts us most is that we are totally unaware of the reason for this extreme step,” said Tina’s father Ramesh Yadav, 67, who retired as a class IV employee of the state government. “Had our daughter spoken to us about whatever problem they had, we would have tried our best to resolve it.”

Amit and Tina got married in 2017. The two were distantly related from Tina’s maternal side. Tina was a graduate and her family was told that Amit was an engineer. But a police probe revealed that he had failed his class 12 exams. Amit lived in Indore with his parents, but moved to his maternal grandparents’ home in Sagar after his father fell sick. After marriage, Amit tried his hand at business with help from Tina’s uncle; it failed, and he suffered a loss of Rs8 lakh. The couple then returned to Indore with their daughter in 2019. Soon, the pandemic-induced lockdown began. Amit and Tina were financially dependent on her parents. Tina and the children would spend the day with her parents. She would take meals to Amit during the day and return to the rented room at night with the children. Once the lockdown was lifted, Amit would leave home early morning lying that he was going to work.

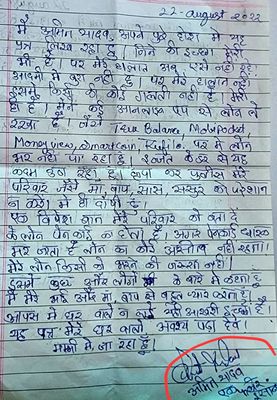

Their financial woes hung heavy in their almost bare room. Amit had failed to pay the rent―Rs2,500 a month–for eight months and also a few monthly instalments (Rs1,200) on a Rs17,000 mobile phone. In his suicide note, he said that he was unable to repay the loan taken from five apps and was taking the extreme step “out of fear of (losing) dignity”.

The police, however, found that Amit’s debt would not have exceeded Rs40,000. Also, he had repaid some of the loans he had taken via apps. In documents provided by four app companies, there was no record of harassment calls or messages, said Nimish Agrawal, deputy commissioner of police, Indore.

Bhagirathpura police sub-inspector Mahesh Singh Chouhan, who investigated the case, said that it looked like the couple had a tiff over financial issues, and Tina might have given the children tea mixed with poison and later consumed it herself around 3am. A shocked Amit might have hanged himself about four hours later, after writing the two-page suicide note.

Tina’s mother, Gangabai, said her daughter was normal the day before the suicide. Gangabai, Tina and three of her four sisters had gone on a trip to Ujjain to visit the Mahakal temple. “She was very normal all through that day and enjoyed the trip despite the heavy rain,” said Gangabai. “At night, Amit came to take the kids up one by one. That is the last time we saw them alive.”

That grief-tinged bafflement resonates with many families across India―cases of mass suicides or familicides, where a family member kills others and dies by suicide, have been reported with shocking regularity from different states during Covid-19. The pandemic lugged around with it Pandora’s box―out came loss, of life and livelihood, followed by loneliness. And then came the tipping point―losing one’s mind. Economic distress along with aggravated mental health issues pushed many to suicide.

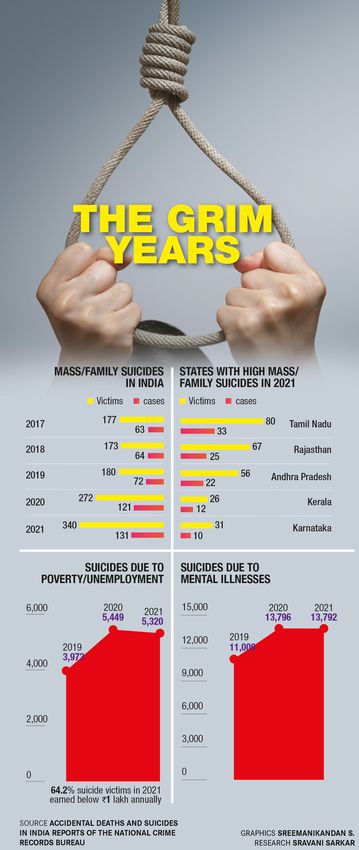

And, statistics prove that. The Accidental Deaths and Suicides in India (ADSI) report of the National Crime Records Bureau (NCRB) indicates a rise in the cases of mass/family suicides from 72 in 2019 to 131 in 2021. The report does not list the causes for mass suicides separately. But for suicide cases, the 2021 data shows that 5,320 of 1.64 lakh suicides were due to poverty and unemployment. In 2019, it was 3,973, and in 2020, it stood at 5,449. Of all the suicides in 2021, 64.2 per cent were by people with less than Rs1 lakh annual income. Another 31.6 per cent were by those earning between Rs1 lakh to Rs5 lakh annually.

Moreover, an analysis of the NCRB data by NGO Vikas Samvad showed that suicides due to mental illnesses rose from 11,009 in pre-Covid 2019 to 13,796 in 2020. The number was almost the same in 2021―13,972.

Sachin Jain of Vikas Samvad quoted a recent analysis of 27.69 crore people registered on the e-SHRAM portal of the Union government after the pandemic. It showed that over 94 per cent workers in the unorganised sector were earning less than Rs10,000 per month. “This data when matched with the NCRB data on financial status of persons who died by suicide makes the role of economic distress clear,” he said. “This, when compounded by physical and mental health issues that escalated during the pandemic, has made a big impact on people. Many do not see a way forward, especially when they have family responsibility.”

Given the spate of familicides in the past few months across the country, experts fear that the numbers will only rise in 2022. One such incident was recently reported from Chennai. On September 20, Ramkumar, 37, a clerk and sole earner in a family of four, called his office, saying that he wanted to take leave so as to die by suicide. The police were immediately informed, but by the time they broke open the door to his house, Ramkumar, his mother Meenakshi, 67, widowed sister Santhana Lakshmi, 40, and autistic daughter Shanmuga Priya, 18, had apparently consumed poison. They were rushed to the hospital. Santhana Lakshmi and Shanmuga Priya were declared dead on arrival; Ramkumar and Meenakshi died the next day. The police said that Ramakumar had taken a loan of several lakhs, which he was unable to repay.

In a gruesome instance this May, L. Prakash, 41, a techie, killed his sedated wife and two children, aged 13 and 8, using an electric saw in Pallavaram, Chennai. He then used the saw on himself. The saw was reportedly running when the bodies were found by Prakash’s father-in-law. The police said that Prakash had borrowed money during the pandemic to help run his wife’s drug store. The inability to repay it drove him to suicide.

Madhya Pradesh saw nine such cases between April and August 2022. In a particularly tragic tale in Badi town of Raisen district, jeweller Jitendra Soni, 37, strangulated his wife Rinki, 35, and sons, aged 13 and 10, before hanging himself on April 26. Only the 10-year-old survived. Four months later, Jitendra’s father, Dhanraj Soni, 62, also died by suicide.

Jitendra’suicide note mentioned unpaid loans and a land dispute with the government, but did not blame anyone. He wrote that he killed his family to prevent lenders from harassing them. The elder Soni’s note named four moneylenders who harassed him following Jitendra’s death.

Amrit Meena, Raisen’s additional superintendent of police, said that a murder case was registered against Jitendra, but the case was closed owing to his death. A case of abetment to suicide against the moneylenders was registered in Dhanraj’s death, but the family refused to pursue the matter further.

Rinki’s uncle, Mahesh Soni, said that she had told her family about Jitendra’s extramarital affairs, but there were no indications of any major turmoil. A teacher, he added that people should turn to family and friends if depressed, and they could get the necessary help for them.

But what if you doubt your own family? Manikuttan, 52, who used to run a tuck shop in Thiruvananthapuram, was found hanging from the ceiling in his home on July 2; his wife Sindhu, 36, sons Ajeesh, 15, and Ameya, 13, and aunt Devaki, 80, were found poisoned to death. The police said that Manikuttan poisoned the others before killing himself. Manikuttan’s mother, Vasanthi, had a narrow escape as she did not eat with them.

“Manikuttan’s relations with his family members were strained,”said circle inspector Vijaya Raghavan, who was part of the investigation team. “He suspected that his wife had extramarital affairs.” There were financial troubles, too. Apart from the tuck shop, Manikuttan was also into farming and had a timber business. He had leased a mango orchard in Tamil Nadu, funded by loan sharks. But the pandemic ruined his plans and threw him into a debt trap.

More than a fortnight later in Nagpur, Maharashtra, Ramrajatala Bhat, 58, set his car on fire in a bid to kill his wife, Sangeeta, 55, son, Nandan, 25, and himself. He died on the spot, and the others a week later. Chandrakant Yadav, in-charge of Beltarodi police station, told THE WEEK that Bhat’s suicide note named financial distress as the reason for the suicide.

“Suicidal tendencies occur in people when they are not able to open up to people around them,” said Dr Vasanth R., consultant psychiatrist, Fortis Malar Hospital, Chennai.

Alimi Srinivas, 52, from Metpally town in Telangana, said that he wished someone from his sister’s family had talked to him about their financial problems before deciding on a suicide pact. In January, Srinvas’s sister, Sri Latha, 50, husband Pappula Suresh, 56, and sons, Akhil, 27, and Ashish, 24, left their Nizamabad flat for Hyderabad after switching off their phones. After a brief stay, they headed to Vijayawada in Andhra Pradesh. They checked into a motel, visited Kanaka Durga temple and checked out, only to return to the motel after a while. Inside their room, all four allegedly injected themselves with insulin. Sri Latha and Ashish died soon after. Since Suresh was diabetic, the insulin perhaps had a neutralising effect. He survived, and so did Akhil. A few hours later though, the duo jumped to their death in the Krishna River. “Who commits suicide like that,” asked Srinivas.

Suresh ran medical shops and owned an agency that distributed medical equipment. And, Akhil had invested in a petrol pump. The family led a comfortable life till the pandemic upended it―their investments in the petrol pump and a nursing home came a cropper. Before ending their lives, Suresh and Sri Latha sent Srinivas audio recordings of conversations they had with financiers who threatened them with dire consequences. They also named the loan sharks.

The financiers have been arrested and the case is in trial. But Srinivas is yet to fathom why his family took the step. “As per my knowledge, they had a debt of Rs50 lakh. Even if it was Rs1 crore, there was no need for them to die as the children could have worked hard and repaid it,” he said. “But the financiers made it impossible for them to live. I got to know that they were slapped inside their home by goons sent by the financiers. When I opened their flat in March, there was blood all over. I do not know what caused it.”

Analysing the case, Akheel Siddiqui of Hyderabad-based Roshni Counselling Center, said, “The person would have felt helpless as debts rose beyond his reach. His concern would have been to save his family from moneylenders.”

In a puzzling case in Delhi, a family of three died by inhaling noxious fumes from store-bought braziers on May 21. Manju Shrivastava, 55, and her two daughters―Ankita, 30, and Anshika, 26―were known to be quiet and unobtrusive. The police reportedly found a handwritten note outside the door warning people of the hazardous gas inside and with instructions on how to ventilate the room before entering.

“There were seven-eight notes inside the house explaining why they took this step,” said an eyewitness who discovered the bodies on bed, with their mouth covered in blood. “It was mostly out of financial distress after the girls’ father, Umesh (a chartered accountant), died the year before (due to Covid-19).” Manju had been ill for a long time and the girls had reportedly slipped into depression after their father’s death.

Rajinder Singh, a Delhi-based psychoanalyst, finds the aspect of smoke emanating from a sealed room particularly interesting, besides the fact that there were multiple suicide notes. “It is almost as if they wanted people to find them,” he said. “They desperately wanted their stories of helplessness and distress to be heard, something they could not do when they were alive. They wanted the smoke from a long-festering fire to seep out and engulf the world outside, for the society to be implicated for driving them to this state.”

Depression, said Singh, worked like a contagion in a family. “Even if one family member is dejected and down in the dumps, others around him are bound to be affected,” he said. “And, in some cases, that one unhappy member is highly persuasive in convincing others―although they might initially protest―to see the futility of earthly existence.“

According to Delhi-based journalist Dayashankar Mishra, who runs a suicide prevention initiative called Jeevan Samvad, mental health issues, social beliefs like superstitions and patriarchal gender roles play a major role in mass suicides. “In [such] cases, often the instigator is the male head of the family, who has a strong feeling that his family might not be able to survive without him,” said Mishra. He suggests mass-level counselling facilities, mood swing tracking by friends or family, and revival of family communication as ways of preventing suicides.

Siddiqui said that apart from NGOs, governments, too, have a role to play in tackling suicides. During the pandemic, Kerala, which has a mental health policy in place, launched a scheme named ‘Ottakkalla, Oppamundu’(You are not alone, we are with you) to help children tackle depression and suicidal tendencies. In 2020 alone, 324 children died by suicide in Kerala. In 2021, the state launched another suicide prevention scheme―Ninavu―under the Integrated Child Protection Scheme.

The Madhya Pradesh government recently constituted a task force that would make recommendations for drafting a suicide prevention policy. Indore police commissioner Harinarayan Chari Mishra has launched a suicide prevention helpline―Sanjeevani. “Our experience suggests that there are some crucial hours before depressed/upset people take such extreme steps,” he said. “If they can get help during that period, the suicidal thoughts pass over.”

―With Lakshmi Subramanian, Rahul Devulapalli, Nirmal Jovial and Sneha Bhura