It is an online lecture called ‘The science of deformation’. The speaker is Prof Rajesh Prasad of IIT Delhi, an expert in applied mechanics. He asks the students what seems to be a fairly straightforward question: “If steel hits ice, which one do you think will break—steel or ice?”

Not so fast.

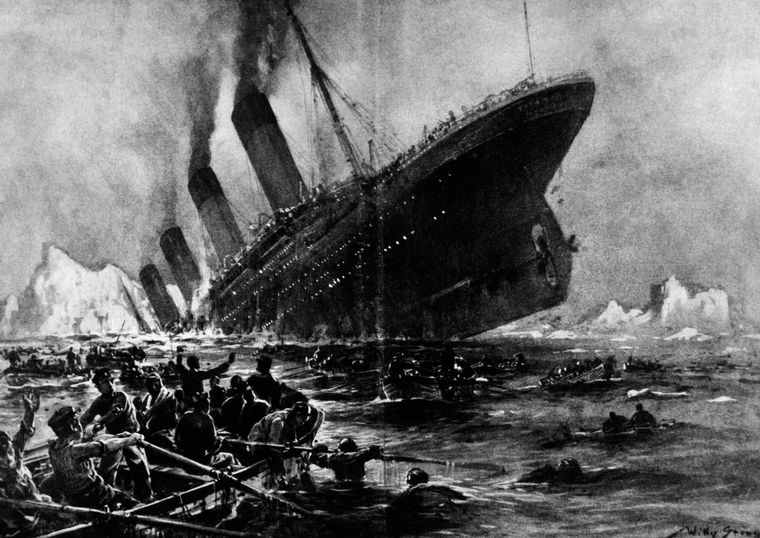

The question was preceded by a sequence from the film Titanic. The protagonists, Jack and Rose, climb on to the stern rails as the giant vessel breaks into two and is swallowed by the ocean. The connection to the question is obvious. The Titanic had been the largest moveable object made by man until it struck an iceberg and sank in the Atlantic on the midnight of April 14, 1912, killing more than 1,500 passengers and crew members. The ship was made of 46 million kilograms of the finest steel available, and yet it had crumbled like a cookie when it hit the iceberg.

“The question is,” asks Prasad, “Why did the Titanic sink so easily? The ship’s steel was more than an inch thick—a very high-quality steel at the time.”

Soon, Prasad begins to explain why the ship went down, using jargon that sounds as poetic as it is esoteric—elastic and plastic deformation, ductile and brittle fracture, and so on.

The lecture, available on YouTube, is just one example of how the classic film based on the ‘unsinkable’ ship continues to be a talking point in India. Indeed, ‘Titanic the steel behemoth’ may have sunk in ice-cold waters, but ‘Titanic the movie’ continues to sail majestically in the warm sea of public consciousness. Twenty-five years since its release, James Cameron’s Titanic has become more than an operatic tragedy; it has turned into a cultural touchstone that can enliven even a tedious physics lesson.

When it was released in 1997, Titanic heralded the entry of global blockbusters into the heart of India. Dutta Khuri of Assam still remembers the time when the entire state was gripped by the Titanic craze. Khuri’s father, Hemant Dutta, was a dramatist who was part of Kohinoor, the famous mobile theatre company founded by the thespian Ratan Lakhar. “Kohinoor staged the Mahabharat even before it reached Indian television. We showed Pompeii before Hollywood turned it into a movie,” says Khuri.

One of Kohinoor’s most memorable plays was Titanic, which was staged 400 times across Assam in just 10 months after its premiere in 2000. “James Cameron took audiences in cinema halls to the Atlantic Ocean; we brought the Atlantic to the stage for the people of Pathshala,” says the 43-year-old Khuri, who was in college when the play opened in Pathshala, a small town in Assam’s Bajali district that is well known as a hub of mobile theatre.

Kohinoor’s Titanic had a 200-member cast and crew. For the play, Dutta and Lakhar mounted an elaborate set—polystyrene (thermocol) was used to build a replica of the giant ship and the iceberg, while the Atlantic was recreated with a combination of plastic and light. The thermocol iceberg broke with an impressive sound effect, and the famous arms-outstretched-like-wings scene in the film was recreated by a clever manoeuvring of the movable stage.

The audience, most of whom had never seen the Cameron film, were mesmerised. Busloads of people thronged the village ground to watch the blockbuster play. “My parents almost needed security to manage the crowds,” remembers Khuri. “Among those invited were members of the Ulfa (United Liberation Front of Assam) and the NDFB (National Democratic Front of Bodoland). The NDFB wanted to form a committee and restage the Titanic but our parents flatly refused. NDFB pressurised Kohinoor theatre a lot back then but no one bothered. The show just went on and on.”

Kohinoor was staged at Delhi’s National School of Drama as well. “We were invited to Berlin to take our Titanic there, but couldn’t because of financial constraints,” says Khuri.

Those who have seen the film cherish their favourite moments. “The ‘I am flying’ pose of Kate Winslet and Leonardo DiCaprio is a dream image of love,” says Abhay Kumar, poet-diplomat and India’s ambassador to Madagascar and Comoros. “Decades ago, when I was visiting the Andamans with my IFS batchmates and we were cruising from one island to another, we would often take turns to mimic that pose on the bow of the ship we were travelling in. For us, it symbolised freedom, achievement and success.”

Bibhu Prasad, project manager in a logistics firm in Bengaluru, was a teenager when he first saw the film. Like many others, he was awed by the film’s scale and special effects, but after the fourth and fifth viewing, the overarching feeling he gets is sadness—about how it is impossible to find a love so pure and self-contained as shown in the film. “Titanic teaches you to trust your own inner voice about how you feel about another person,” says Prasad, 31.

For Abhilasha Ghosh, a 29-year-old publicist from Kolkata who first saw Titanic when she was 17, the film is not a love story at all. “It was all about Rose’s emancipation,” she says. “Jack was only the agent to get her to plunge into a whole new world. I am very curious to know how Rose rebuilt her life from scratch after she left everything behind. How she really survived to tell the tale. There should be a sequel just for that.”

For Baadal Nanjundaswamy, a street artist noted for his 3D work, the pandemic has given a cheeky twist to the trope of everlasting love in Titanic. During the lockdown of 2020, he created a large mural in Bengaluru’s RT Nagar, showing Jack hesitating to join Rose at the stern rail. Both of them were also shown wearing masks. “In those unreal times, we became scared to go anywhere near our loved ones,” says Nanjundaswamy. “Even Jack couldn’t help avoiding Rose under the circumstances.”

Why is Titanic so enduringly popular in India? Perhaps, because it may be the most Bollywood of Hollywood films. In his 2008 book Seduced by the Familiar: Narration and Meaning in Indian Popular Cinema, National Award-winning critic M.K. Raghavendra dissects how Cameron’s vision of love allows for an Indian reading. Jack being awestruck by Rose’s beauty in the very first meeting, then rescuing her from the clutches of her rich, selfish fiancé and stern, unrelenting mother, their union being blessed by the maternal figure of Molly Brown, Jack’s ultimate sacrifice and his extraction of a promise that Rose will live, love and bear children, and how Rose remains faithful to Jack’s memory—all of these are essentially tropes that Hindi cinema has long explored.

“When the film came out in India, it was for the very first time I saw emblems of a Hollywood film emblazoned on autorickshaws,” says Raghavendra. “The sinking ship motif could be seen on autos, where normally you would see an Indian actor or a Hindi movie poster.”

The Titanic disaster is the Mount Everest of shipwrecks. Everyone wants a piece of it. And there had to be a master storyteller who would capture the mosaic of heroism, greed and tragedy that this legendary maritime incident exemplified. But can India deliver its own ocean drama? Who could be the contenders to direct a motion picture epic on a scale as grand as the Titanic? The sinking of SS Vaitarna in 1888 has been dubbed as the Titanic of Gujarat and there was once an attempt to make a film on it in 2017 starring Rana Dagubatti as the investigator/researcher of the disappearance of the steamship. The project never took off. Maritime or naval disasters in South Asia haven't really been explored on celluloid as a feature film. "This entire thing of exploring the past by focusing on a single historical event is missing in India. And the ones that are there veer towards sentimental patriotism," says Raghavendra.

According to him, a reason for the lasting appeal of Titanic is the one key factor that sets it apart from another iconic tragedy—Romeo and Juliet. Titanic, he says, is not as grim as Romeo and Juliet; it is, instead, a “happy tragedy”.