The only reason April 2022 was not the hottest April on record in the country is because northeast India had heavy rainfall, an occurrence so unexpected that even the Indian Meteorology Department (IMD), which now prides itself on accurate forecasts, said it had gone wrong. In northwest and central India, April broke all heat records.

The heat wave (which the weatherman describes as temperature above 40 degrees Celsius and 4.5 to 6.5 degrees Celsius above normal for that time of the year) may be ebbing from parts of the northwest and central lands, but the relief is temporary. April is technically late spring or early summer, May is the hottest month, while for the northern plains, June is as bad, if not worse. Forecasts grimly say that May is likely to witness above normal temperatures.

The World Meteorological Organisation noted that while it may be premature to put the onus for the extreme heat on climate change alone, it was consistent with what is expected in a changing climate—heat waves are more frequent and more intense, and starting earlier.

The early heat could have cascading effects. The Himalayan ice melt could start early, not just further affecting the glaciers, but also bringing gallons of melt rushing down the mountain rivers in quantities that could cause flooding and calamitous events. A very fine climatic balance, perfected over millennia, is poised to crash.

In the immediate weeks, the additional water could be a blessing. The early heat has upped water and power demand, and inter-state bickering is escalating. With parched waterbodies and ground water down to abysmal levels, India is likely to feel the impact of the extreme climate event in many ways. Just as last year the railways ran oxygen trains to deal with the Covid-19 wave, this year passenger trains are being sidelined to ferry coal for generating power. For every one degree rise in temperature, the efficiency of electricity transmission drops by one to two per cent, said Hem Dholakia, lead specialist (research) at the Coalition for Disaster Resilient Infrastructure (CDRI).

It is no surprise that the PMO is convening meetings with stakeholders in the states to prepare for the weeks ahead. Following the IMD’s warnings, the Union health ministry, too, reached out to states, asking them to give out daily heat bulletins and implement the National Action Plan on heat related diseases. This entails ensuring adequate water supply, warning people in advance, and stocking up medical centres to deal with dehydration and heat stroke cases.

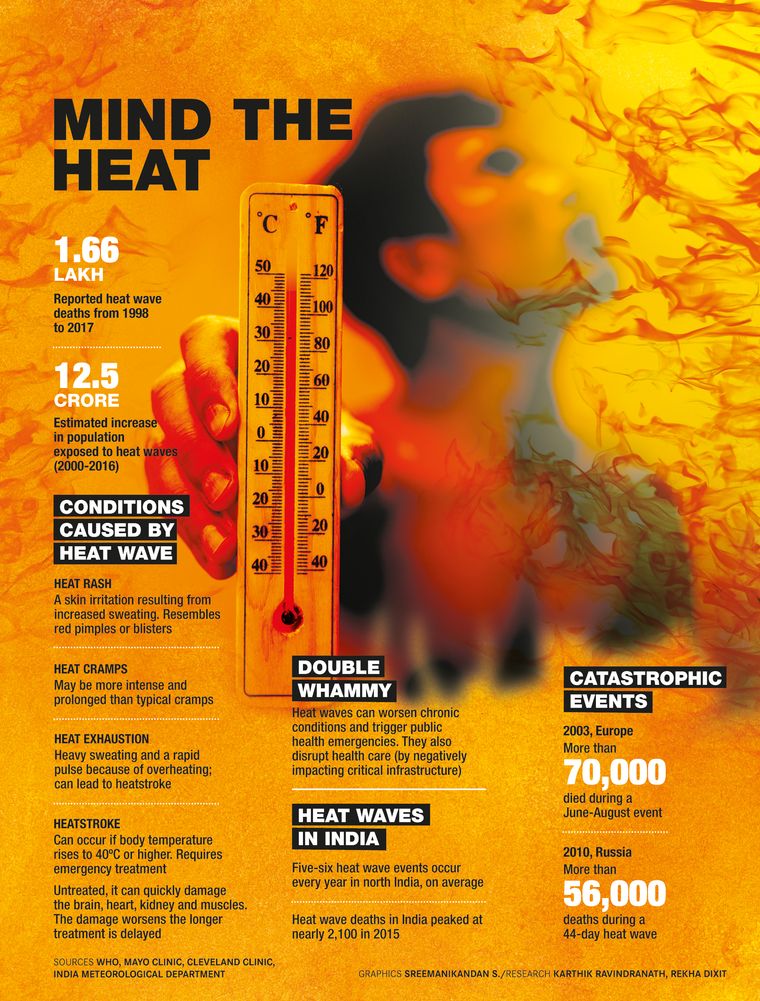

Memories of 2015 have not gone, when the country registered over 2,100 deaths due to heat waves, the highest since 1971. The unofficial toll must be several times higher. In 2015, the country declared heat wave as a “disaster’’ under the National Disaster Management Act, given its impact on human life and loss of productivity.

April also brought to light a phenomenon experts often talk about—the urban heat island. In Delhi, for example, on April 29, while the Safdarjung station (which is considered the standard for the city) notched the second highest ever April temperature of 43.5 degrees Celsius, another station at Akshardham recorded 46.4, a difference of three degrees. Urban heat islands develop due to various factors, like concretisation, industrialisation and high population density, often in combination with a decreased green cover. Concrete surfaces and roads have greater heat reflectivity, causing the temperatures in these pockets to be much above those of surrounding areas. “The maximum impact of urban heat islands is on minimum temperatures,’’ said IMD director general M. Mohapatra. Thus nights brings little relief.

The summer ahead is dire. And the summers in the years to come will test our preparation towards climate crisis mitigation. By 2050, 60 crore Indians will be living in urban areas. Climate resilient city planning is an urgency, said Anjal Prakash, lead author of the sixth assessment report, Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change.

Climate change is the result of 200 years of anthropogenic activities, and localised cosmetic measures may not stem events which are caused because of global changes. For instance, temperature rise in India is not necessarily due to activities in India alone. However, as one of the countries most vulnerable to climate change events, India has to develop mitigation measures towards heat events as well.

Understanding why a particular locality has become an urban heat island may require some scientific investigation. However, there are certain interventions that work irrespective of the cause. “We need to construct infrastructure for Indian needs and not ape the west,’’ said Prakash, a critic of using glass as construction material. “In a country with so much sunshine we do not need glass buildings, within which the cost of cooling goes up. We need to have passive cooling built into our architecture, for which we have enough traditional examples. Take the Hawa Mahal in Jaipur, where temperatures are easily around four degrees cooler than outside. And we have to build back our green and blue infrastructure.’’

Indeed green cover and water bodies influence microclimates, bringing down temperatures by just that one or two degrees which could mean the difference between life and death. Simply ensuring fountains are on in the hot days is effective, as is keeping open public parks and gardens for people to take refuge in, said Dholakia.

Ahmedabad was the first city in the country to have a heat health action plan, which has been replicated on a national scale. The actions suggested are determined by local circumstances, the dry heat of north India needs different measures from the humid heat of the coasts. Unfortunately, while the first step of the plan, which entails the IMD giving out short term forecasts with a colour coded alert system, is in place, the actions that local authorities need to take on them remains sporadic. “There should be a system for declaring certain activities, like construction, not be done during the hottest hours. Or that school timings be advanced based on the weather alerts,’’ said Prakash. With climate events through the year impacting school life—floods, smog, extreme cold—instead of declaring holidays, authorities will now need to work their way around these events.

Cool roofs is another initiative, working well for both upscale infrastructure as well as low cost tenements. Rooftop gardens is one measure, simply painting tin roofs with white reflective paint instead of black, heat absorbing paint, again brings temperatures down by a degree or two.

March was the hottest on record, April was cruel. Will India be able to mitigate the miseries of May? It is one thing to recommend that a seamless electric and water supply be maintained and an entirely different challenge to ensure that it happens.