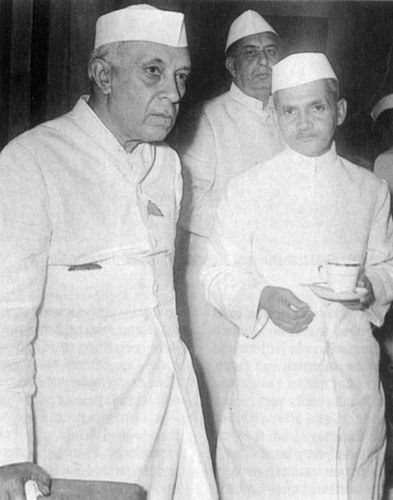

In sharp contrast to his political guru Jawaharlal Nehru, Lal Bahadur Shastri, 15 years younger, was very much of an indigenous upbringing. Shastris are normally Brahmins. But Lal Bahadur was a Kayastha or of a different caste. He earned the title Shastri—a person with a higher learning—after securing first-class marks in his graduation at the ancient city of Varanasi, with its plethora of temples, quite holy to devout Hindus, in Uttar Pradesh. This, therefore, became his surname. Influenced by Gandhi and Nehru in his formative years, as the mass movement for Indian independence mushroomed, he came to assimilate and appreciate Gandhian secularism and Nehruvian socialism.

After the country’s freedom, he was appointed minister of India’s state-owned railways—one of the world’s most widespread networks—in Prime Minister Nehru’s cabinet. Dedicated and scrupulously honest, he famously resigned in 1956, taking moral responsibility for a train accident. Frequent previous such incidents had been worrying both the government and the public. In August of that year an accident occurred in which 112 people lost their lives. Shastri put in his papers. Nehru, though, coaxed him to continue. Then in November, another accident took place, this time killing 144 passengers. On this occasion, there was no withdrawing his notice.

Announcing Shastri’s departure from the government in parliament, Nehru stated with a heavy heart: “I should like to say that it has been not only in the Government, but in the Congress, my good fortune and privilege to have him as a comrade and colleague, and no man can wish for a better comrade and better colleague in any undertaking—a man of the highest integrity, loyalty, devoted to ideals, a man of conscience and a man of hard work.”

On his return to government after the 1957 general election, he increasingly won the prime minister’s trust and was eventually assigned the powerful and prestigious portfolio of home affairs.

In the early 1960s, food production in India fell below demand, thereby necessitating imports to feed a ballooning population. Subsequently, in September 1962, India experienced a harsh humiliation, with China invading the country before retreating to its soil under western, particularly American, pressure. United States Air Force and (British) Royal Air Force planes descended on India’s forward areas as a show of solidarity with India.

The bitter pill inflicted by the Chinese was not merely testimony to the unpreparedness of India’s armed forces, but a failure of New Delhi’s foreign policy, over which Nehru presided, he holding additional charge of the ministry of external affairs. Nehru prided himself on his understanding of international matters. But he had misread the Chinese communist regime.

North-East Frontier Agency or NEFA, later renamed the state of Arunachal Pradesh, which the Chinese claim as being South Tibet and part of its territory, was ceded to India in a tripartite agreement (Tibet being the other party) in 1912 but not ratified by China in 1914. British India recognised Chinese suzerainty, not sovereignty, over Tibet at the time. Consequently, China sweeping into Indian soil in disregard of what historically emerged as the Sino-Indian border, known as the McMahon line, shook him immensely.

In 1958, Nehru had expressed a desire to quit office. He told a meeting of the Congress parliamentary party: “I feel now that I must have a period when I can free myself from this daily burden and think of myself as an individual citizen of India and not as prime minister.”

He had earlier quite candidly complained to the press: “I have said that I feel stale. My body is healthy, as it normally is. But I do feel rather flat and stale and I do not think it is right for a person to feel that way and I have to deal with vital and very important problems.”After the China debacle, though, his health perceptibly declined.

In January 1964, he suffered a stroke at Bhubaneswar, where he had gone to attend a session of the All India Congress Committee (AICC). With such a colossus laid low by illness, a question first asked the previous year in a book by Welles Hangen titled “After Nehru, Who?”noticeably resurfaced. Britain’s Guardian newspaper noted on January 23: “It looks as if Lal Bahadur Shastri is being ‘evolved’as the next Indian Prime Minister.”

Meanwhile, following the setback on the China front, the Congress’s popularity began to wane. Indeed, in 1963, Kumarasami Kamaraj Nadar, then chief minister of the southern state of Tamil Nadu, had proposed to the Congress working committee—their highest decision-making body—that some state chief ministers and cabinet ministers in the central government should quit their positions to devote time to party work.

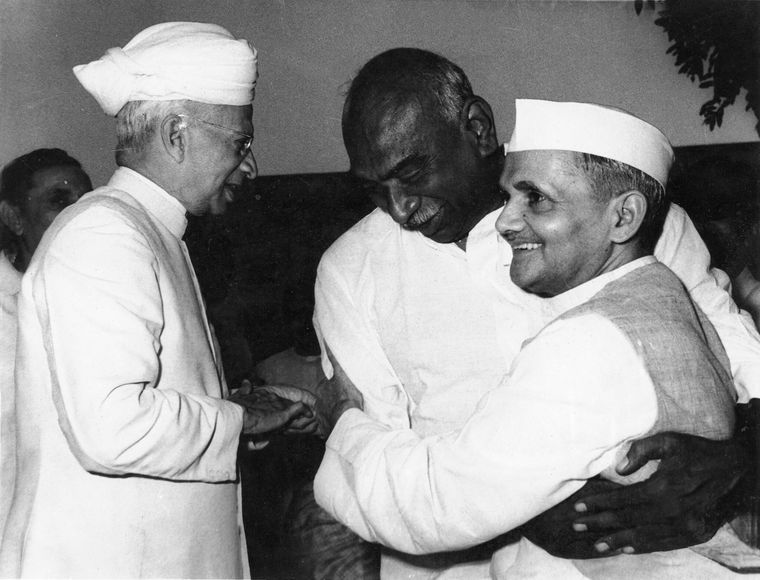

Accepting this idea, christened the “Kamaraj Plan”, several ministers in the Nehru administration resigned, including Shastri. That notwithstanding, by the conclusion of the Bhubaneswar conclave—and Kamaraj had become party president by then—Shastri had clearly surfaced as the most likely successor to Nehru, enjoying both the prime minister and Kamaraj’s confidence.

Shastri returned to the cabinet as minister without portfolio. In a conversation between him and Nehru in Hindi, he asked: “What work will I be doing?”The prime minister replied: “You will have to do all my work.”This became de jure when Nehru passed away on May 27, 1964.

Shastri’s senior aide, Chandrika Prasad Srivastava, later an illustrious secretary-general of the International Maritime Organisation in London, revealed in his biography of Shastri that the latter met Nehru’s daughter, Indira Gandhi, on May 30 and suggested that she should succeed her father. Shastri confided in Srivastava that he had conveyed to her in Hindi: “You should now assume responsibility for the country.”According to Srivastava, Indira refused the offer, “saying she was then in such grief and pain that she just could not think of contesting the (party) election (for the post of prime minister)”.

The next day, the Congress working committee resolved that unanimity was the way forward through the efforts of Kamaraj. On June 2, at a meeting of the Congress parliamentary party, Gulzarilal Nanda, who had been officiating as interim prime minister, proposed 59-year-old Shastri’s name as leader. This was seconded by Morarji Desai, a right-wing politician, who had himself been a strong contender.

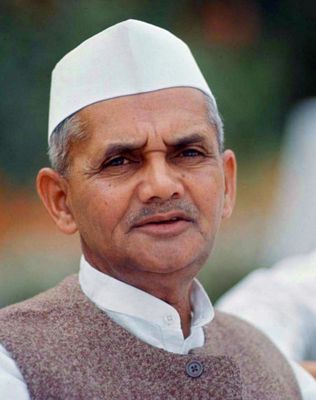

Shastri was all of five feet in height and was unflatteringly portrayed in foreign media as a “little sparrow”. The Pakistani military dictator across the border, Field Marshal Ayub Khan, misread his humility and simplicity for weakness. There was concealed within a steely resilience.

The Pakistani establishment, Khan included, deemed post-Nehru India and Shastri to be vulnerable. It also interpreted the Indian army’s capitulation to Chinese forces in 1962 as its un-readiness. The combination of the two was sensed by India’s neighbour as an opportunity to annex the disputed territory of Kashmir.

Thus, in April 1965, Khan embarked on seizing the Valley contiguous to Islamic Pakistan, which it claimed on the basis of its Muslim majority. Hostilities broke out between the two countries in September of the same year.

Historian Ramachandra Guha records: “He (Shastri) displayed a knack of taking quick and decisive actions during the war.”The Pakistanis overlooked the fact that, while Indians were caught napping against the Chinese, a programme of defence production and purchase initiated by V.K. Krishna Menon—who was compelled to resign as defence minister after the China embarrassment—had begun in the late 1950s and had partially come to fruition by 1965. Besides, the Indian Army was now commanded by General Joyanto Chaudhuri, who as a captain in the British Indian Army in World War II had distinguished himself, indeed been decorated for his services, for his tank warfare capabilities in North Africa under General Bernard Montgomery against the redoubtable “desert fox”German Field Marshal Erwin Rommel.

Overrunning Kashmir was Pakistan’s overriding ambition. However, there was another friction over a barren swamp, the Rann of Kutch in the western Indian state of Gujarat. Following skirmishes between the two nations, they were persuaded by the British prime minister Harold Wilson to set up an international tribunal to settle the disagreement. (Three years later, Pakistan was awarded 350 square miles of this territory as against its claim of 3,500 square miles.)

After being restrained by Wilson, Khan imagined the Indian Army would not be able to withstand a surgical strike at a narrow segment of India south of Jammu & Kashmir, thereby sealing off the state from the rest of India. Khan assumed Muslims in J&K were inherently hostile to Hindus and therefore to India. He attempted to fuel an uprising by covertly sending in saboteurs. He rudely discovered that Indian Kashmiris were in no mood to cooperate and in fact swiftly neutralised this design.

In early August, tens of thousands of Pakistani regulars had crossed the United Nations mandated Line of Control in Kashmir. On September 6, India counter-attacked in Punjab, thus into the Pakistani heartland. The western press commented the Indian assault was “not unprovoked”.

The Indian troops came within range of the airport in Lahore, Pakistan’s second biggest city and the capital of its Punjab, despite Pakistan’s much higher ratio of troops and more modern military hardware, including American Patton tanks and F-86 Sabre jets, compared with India.

The confrontation, though, was heading for a stalemate when the UN called for a ceasefire, which the two nations accepted. Neutral observers estimated that the Indian army cornered 710 square miles of Pakistani soil and the Pakistani army 210 square miles of India’s territory; that India lost 3,000 soldiers as opposed to Pakistan losing 3,800.

India actually faced a multi-pronged threat from China, Indonesia and Iran, which sided with Pakistan in the conflict. Before fighting escalated, Beijing declared its full support for Pakistan. It sent a threatening note to India citing “successive serious violations of China’s territory and sovereignty by Indian troops.”It demanded: “India dismantle all the aggressive military structures it has illegally built beyond or on the China-Sikkim border, withdraw its aggressive armed forces and stop all its acts of aggression and provocation against China in the western, middle and eastern sectors of the Sino-Indian border.”

India firmly responded: “The Chinese protest is intended to malign India and to cause confusion in the international world and also to prepare a pretext for any illegal actions directed against India which the Chinese Government might be contemplating.”

Shastri shrewdly called Beijing’s bluff. In his view, China could not go beyond rhetoric as the world knew its accusations were unfounded. Stuart Symington, a senior member of the US senate foreign relations and armed services committee, said America could intervene, hinting at the Pentagon’s interest in Chinese nuclear installations.

As the war proceeded, the Soviet Union in no uncertain terms cautioned China against “incendiary statements”. More materially, China’s mal-intentions were nullified by the Soviet Union warning Beijing that if it moved against India, it would do likewise against China. This reflected a significant shift in Soviet policy towards to India, which was to climax in a Friendship Treaty in 1971 before the liberation of East Pakistan (now Bangladesh) by Indian troops.

Also in 1965, as a sign of solidarity with Pakistan, Indonesian naval vessels steamed towards India’s east coast before being ordered to turn back. This volte-face occurred after Shastri sent Biju Patnaik, father of the current Odisha chief minister Naveen Patnaik, to prevail upon the Indonesian president Sukarno to abandon the move. Patnaik, an air force pilot during World War II, had in a daredevil mission in the 1940s, before Indonesian independence, rescued Sukarno, then a nationalist leader, when he was hopelessly cornered by Dutch colonial forces.

In effect, Shastri notched up external affairs successes in liquidating second and third fronts. As for the war itself, India was widely recognised as the victor. On stepping into his predecessor’s shoes, the dapper little man in his dhoti, kurta and waistcoat, sporting a moustache had remarked in the Lok Sabha: “I tremble when I am reminded of the fact that this country and parliament have been led by no less a person than Jawaharlal Nehru…”But the diminutive prime minister had metaphorically grown tremendously in stature. He was now an unbridled hero; emerging out of the immense shadow of his predecessor into the spotlight.

During the Indo-Pak war, he coined a slogan “Jai Jawan, Jai Kisan” (Victory to the Soldier, Victory to the Farmer), which immediately struck a chord among the Indian masses. And he would stirringly round off his speeches at mass rallies with “Jai Jawan, Jai Kisan, Jai Hind”(Victory to India).

The Soviet Union hosted peace talks at Tashkent (now in Uzbekistan) between India and Pakistan in January 1966. Shastri and Khan represented their governments. An agreement was duly signed. The next day, while still in the Uzbek capital, the Indian leader died of a heart attack. He was 61.

He had endured a milder cardiac thrombosis in 1958, when he was a cabinet minister, and again in 1964, shortly after becoming prime minister. He was in the habit of working long hours. Srivastava recorded “his working day in the secretariat seldom ended before 10 pm”. When Nehru got to know of this, he rang Shastri and “admonished him in a most caring way”. As Srivastava put it, "the truth was that the privations of his early life and the almost round-the-clock work for many years took their toll”. Hangen had in his book notably forewarned that one of Shastri’s most serious handicaps for the top job was his health. “A former colleague in the (Indian) Union Cabinet says that his first attack caused no lesion but a second or third could be crippling,”he had observed.

Shastri’s belief in secularism and his commitment to implementing Nehru’s vision were never in doubt. But even before he became prime minister, he emphatically demonstrated an ability to win the respect and trust of Muslims, with whom the pro-Hindu Bharatiya Jana Sangh, an offspring of the Hindu Mahasabha and precursor to the current Bharatiya Janata Party, was constantly at loggerheads.

On December 26, 1963, a particularly awkward situation arose in Jammu & Kashmir. A sacred hair of the Prophet Mohammed, preserved for 300 years at the Hazratbal mosque on the outskirts of Srinagar, had disappeared, suspected to have been removed by miscreants. Muslims were infuriated. Hindus and Sikhs, too, joined in expressing their displeasure.

Nehru was nervous. India was always on tenterhooks about fissiparous tendencies among a section of Kashmiri Muslims, with a small faction openly pro-Pakistan. Eight days after the theft, the relic was mysteriously rediscovered at the shrine. Yet the tension didn’t subside, as demonstrators demanded a special viewing in order to deliver a verdict about its authenticity. As the agitation gathered momentum, police fired on mobs, killing people.

The Times, London, reported: “It appears that the demonstrations expressed the continuing public suspicion in Kashmir that the true relic of the Prophet has not been recovered since its theft last month and that the hair now in Hazratbal shrine is not the one that was stolen.”It added: “There must be a danger, at least, that the continuing movement will aim at the Indian government.”Pakistan showed itself to be ever anxious to take advantage of the delicate circumstances and foment communal disharmony in the Valley.

It was freezing in Kashmir; and Shastri unsurprisingly didn’t possess an overcoat. So, Nehru lent him one as well as a carte blanche to deal with the trouble. In Srinagar, leaders of the disgruntled action committee insisted that a team of devotees free of political affiliations should vouch for the genuineness of the relic that had reappeared.

Shastri’s advisers counselled him against conceding the committee’s stand. But he decided to consult with the agitators.

Srivastava disclosed: “Shastri came to the conclusion that, in all probability, the relic was genuine. He then concluded that, in regard to such a holy relic, no Muslim divine or devotee would risk rejecting its sanctity for political reasons. Shastri therefore ruled out the possibility of a mischievous verdict.”Nevertheless, it was a gamble.

On February 3, a special viewing took place. The UK’s Daily Telegraph’s despatch from Srinagar the same day read: “Amid mounting tension, venerable priests meeting in the historic Hazratbal Mosque outside Srinagar…agreed today that the lost and now recovered hair of the Prophet Mohammed was genuine.”

Thousands had thronged the mosque awaiting the ruling. Relief and joy cascaded through them when the announcement was made. “Shastri was literally mobbed by the crowd,”noted Srivastava.

K. Rangaswami, a leading Indian political commentator of the time, was of the opinion that “Lal Bahadur Shastri had returned to the capital (New Delhi) adding another laurel to his credit in the public and political life of India. His asset is his basic nature to deal justly and with tolerance and understanding even towards opponents. It is this quality which won him the affection and the confidence of all groups in Kashmir…”

Sheikh Abdullah, the “Lion of Kashmir”, had long been a political prisoner. It was feared that any further detention would be unhelpful to India as far as the Kashmir situation was concerned. Shastri got Nehru to agree to his release, which paved the way for a further easing of tension in the Valley.

When he took over the reins as head of government, there was, as Srivastava said, “the ever-present danger of communal strife”. He confirms: “Shastri did not believe in the divisive concept of majority and minority religious communities. To him religion was a personal matter, and it could not be the basis of political activity. For all that, he did not believe in amoral politics. According to him, politics had to be founded on those clear moral and ethical principles which are the fundamental elements of all faiths. He wanted every citizen of the country to feel emotionally and intellectually as an Indian first and last, with pride in the country. It was therefore one of his primary aims to foster nationalism, patriotism and secularism, and to promote a national unity which was perpetually threatened by communal undercurrents, as he had seen closely when a cabinet minister.”

In fact, Shastri was annoyed by a BBC report during the 1965 warfare, which said he being a Hindu was ready for a war with Muslim Pakistan. At a public meeting organised in Delhi a few days after the ceasefire with Pakistan, he asserted: “The unique thing about our country is that we are Hindus, Muslims, Christians, Sikhs, Parsis and people of other religions. We have temples and mosques, gurdwaras and churches. But we do not bring all this into politics.”He went on to emphasise: “This is the difference between India and Pakistan. Whereas Pakistan proclaims herself to be an Islamic state and uses religion as a political factor, we Indians have the freedom to follow whatever religion we may choose, and worship in any way we please. So far as politics is concerned, each of us is as much an Indian as the other.”

Shastri’s was only a mere 20-month tenure as prime minister. But he represented a continuity of Nehru’s vision. Under him, the foundation of secularism laid by his predecessor remained unimpaired.

As a general secretary of the Congress, he played a key role in the party’s landslide victories in the 1952, 1957 and 1962 general elections. Both Hindu and Muslim communal forces had gained ground during the 1940s in a political vacuum created by the British incarcerating practically the entire Congress leadership in the aftermath of Mahatma Gandhi’s “Quit India”movement of 1942. Yet, the Jana Sangh won just three, four and 14 seats out of a total of 489, 494 and 494, respectively, in the three elections concerned. Shastri, thus, played a significant part in keeping bigoted thinking at bay.

Shastri never deviated from the principle of preserving secularism. It, of course, helped that the Congress was in a commanding position on the Indian political stage. But his integrity in not permitting dilution of the ideological footprint left behind by Nehru was impressive.

His sudden and untimely death was a manifold tragedy for India. A longer innings would, arguably, have consolidated the nation’s institutions, probably made government more competent and, perhaps, rendered more permanent inner-party democracy in the Congress.

Shastri died with a negligible bank balance and an unpaid loan for a second hand car. His popularity had soared after India blunted the Pakistani military’s sinister designs. This immediately enhanced his authority. With the backing he now enjoyed and given his skilful, steady and fairly swift style of functioning, he was likely to improve governance; and by so doing, irreversibly establish ideals, such as secularism.

The writer is a journalist living in London