This autumn, World Wrestling Entertainment decided to bring back audiences for its shows like Monday Night Raw and SmackDown. With the ‘pando’, or pandemic, raging all over, it started hosting shows at the ThunderDome, a brand-new concept of augmented reality with a thousand LED screens arranged in an arena-like manner. Each screen space is sold as a seat, the ‘virtual audience’ can log in from home and attend the show, almost in person, with their faces beaming in real-time on the screen. With drone cameras, pyrotechnics, lasers and video boards, the experience cannot get more realistic in this age of the ‘new normal’.

The pandemic changed almost everything that was normal. Even our reflexes have altered, and the step-out-of-home checklist—car keys, sunglasses, wallet—now includes a mask. A woman’s vanity pouch in her handbag may or may not have that lipstick tube, but will certainly have a vial of sanitiser, most likely one with a dainty perfume that is more personalised than the industrial, hospital-smelling stuff you find at the entrance to any public place. And on those rare occasions when we actually meet and greet someone, we no longer thrust our hand out for a handshake and try to judge the other person’s character with the firmness of the shake. Instead, we fold our hands in a namaste, or more stylistically do an ‘elbow bump’, desperately hoping the other person does not hit our funny bone, instead.

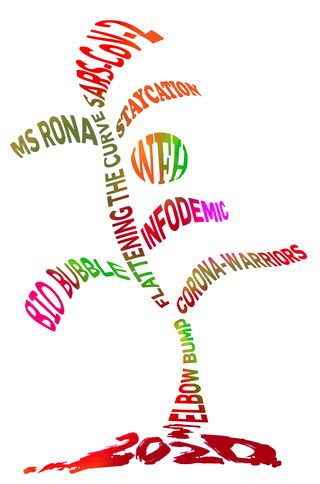

The world needed a whole new vocabulary to describe each of these new experiences. Our language has been evolving as the pandemic progresses from a stage when we could optimistically think of ‘flattening the curve’ by ‘breaking the chain’, and when ‘contact tracing’ was still useful, to the bleakness of accepting ‘community spread’. And now, we are grateful that we have survived the ‘second wave’ and hoping to tide over the ‘third wave’, too, even as we wait for the vaccine. Not everyone believes in vaccines, though. The ‘anti-vaxxers’ have always been around; now, they have been joined by the ‘anti-maskers’. The more virtuous call them ‘covidiots’. These are trying times, what with ‘pandemic fatigue’ setting in.

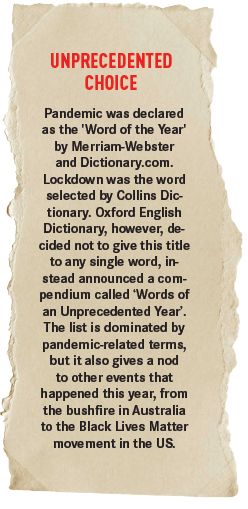

In a year of unprecedented happenings, the Oxford English Dictionary (OED) did something unprecedented, too. In addition to its four quarterly updates on new words that have gained entry into this repository of the English language, it did two special updates to accommodate the rapidly evolving Covid-19 lingo. And, these updates were done while the employees ‘worked from home’, and their cities were under ‘lockdown’.

The most important word coined this year was the name of the disease itself, ‘Covid-19’ (made by fusing the words corona, virus, disease and 19 to indicate the year it began). The disease was christened by the World Health Organisation’s International Classification of Diseases on February 11, but the dictionary had to be updated within months to better describe it, from an “acute respiratory illness” to a “disease characterised by fever and cough capable of progressing to pneumonia, respiratory and renal failure, blood coagulation abnormalities and death.” However, ‘corona’ still remains a popular name for the disease, especially in India. The disease has also been given a female entity (no surprise) with names like ‘Ms Rona’, ‘Aunt Rona’ and ‘la rona’, in other shores.

On the same day, the International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses called the virus ‘SARS-CoV-2’, though in common parlance, it is still referred to as simply coronavirus.

Not every word that has gained currency this year has had such a formal induction. Many have been thrown in by the shovelful into dictionary updates, a lot many still have not made it to the dictionary, yet. In fact, many words are not even new. Some, like ‘personal protective equipment’ or ‘PPE’ and ‘quarantine’, were around for decades, but have become popular now. Others, like ‘isolation’, have been repurposed to fit the requirement of the times, with ‘self-isolation’ becoming a yardstick of responsible behaviour. These, however, are finer points for the pedantic to deliberate over, who anyway miss the wood for the trees. The important point is that the post-corona language would be very different from what was being spoken last year.

The progression of the usage of these new terms and slangs tells the story of how the world’s understanding of things has changed over the last 12 months. Quarantine-inspired words were extremely popular in the spring when people had the novel experience of being forced to ‘stay at home’. In those days, a relaxation was to have a ‘quarantini’, and while at home, what better to do than ‘quarantine and chill’. (This slang echoes ‘Netflix and chill’ and, like the original, has a risque element to it. While the innocent might just accept it at face value, it could also involve the taking of some telling ‘quarantine selfies’). Any which way, this was a better choice than ‘doom-scrolling’ and falling victim to the ‘infodemic’, which the WHO acknowledged as big a problem as the pandemic.

In the early days, while people were told to stay at home, the nuts and bolts of the world worked on those who had no choice but to step out. The doctors, nurses, sweepers, deliverymen and Vande Bharat pilots, all became ‘corona warriors’ or ‘frontline workers’. In fact, ‘frontliner’ entered the OED as a new noun. Not every work could be done from home, so we created the ‘quaranteam’, or a group of uninfected work-mates or families, who isolated themselves from others, and therefore, could meet and work without fear. With the ‘unlocking’, ‘quaranteams’ have given way to ‘bio bubbles’, which more or less means the same. The IPL teams flew to the UAE and lived there in a ‘bio bubble’, isolated from external human contact. Travel restrictions have made those destination holidays impossible, but people are now enjoying ‘staycations’ as they discover the wonders of their neighbourhood, when they are not in WFH (work-from-home). Staycations were first mentioned after the economic doom of 2008 when money was tight, but it is in 2020 that they have come of age, with millennials even combining WFH with a staycation.

A change in destination, however close to home, is a welcome relief when work and socialising now involve a stream of ‘webinars’ and ‘Zoom meets’, and all that ‘screen-time’ is taxing on the eyes, especially for children. And, one has to be vigilant about ‘zoom-bombing’; this attack can be so much worse than the photobombing phenomenon that was born in 2008.

Our hopes and disappointments with drugs can be recorded in how the use of certain pharmaceutical terms peaked and waned. Hydroxychloroquine or ‘HCQ’ was that silver bullet in March and April, and India, sitting with a cache of these white pills, played drug diplomacy, doling out portions to friends and neighbours. As the summer progressed, HCQ fell from grace, and other mouthfuls like Remdesivir and Dexamethasone had their moments of glory. In India, giloy (also known as guduchi) has replaced neem as the healing leaf.

Language is a living entity, unless it evolves constantly, it will be dead. New inventions and new ways of life keep creating new words, or new uses of old words. A quick look at words that entered our lexicon in past decades creates a telling picture of the lives of those times. The 1940s was the time when the Nazis dug ‘mass graves’ for prisoners, while a shortage of nearly everything had people ‘cannibalising’ equipment to get one workable set. It was the time of ‘GI brides’ arriving in the US, with their husbands returning from ‘Ground Zero’, these women often sported a ‘bob cut’.

The post-war decade of the 50s created the ‘angry young man’; was his anger partly to do with the discomfort of squeezing himself into ‘drainpipe trousers’? Indeed, fashion was an ‘overkill’. Meanwhile, the ‘Cold War’ of the past years now created a ‘space race’, and the buzz was about ‘moonshots’, ‘UFOs’, and ‘soft landings’. ‘Fast food’ had just come into being and was not the vile thing it now is considered to be.

By 1962, women began wearing ‘miniskirts’ and in three years, even shortened the name of the garment to ‘the mini’. They also wore ‘flares’, and the ‘flower children’ liked sporting ‘unisex’ looks as they experimented with ‘acid’ and other ‘psychedelia’. The ‘peaceniks’ raised concern about Agent Orange, while in the world of ‘software’, ‘bytes’ and ‘chips’ debuted.

The ‘smiley’ arrived, along with ‘plastic money’, in the 1970s. People took to eating ‘junk food’ at their ‘workstations’. A new age of ‘political correctness’ came into being and fathers began thinking about claiming ‘paternity leave’.

The ‘yuppies’ of the 1980s took to ‘swiping their smart cards’. These ‘30-somethings’ were often ‘dinkies’ or ‘double income, no kids’ couples (later DINKs). So much money made them ‘shopaholics’, and their lives swung between the extremes of the ‘feel-good factor’ and being ‘stressed out’. They began worrying about the depleting ‘biodiversity’ by ‘eco-terrorists’ and advocated ‘eco-friendliness’. They marvelled at ‘email’ and took to deriding ‘snail mail’.

The ‘power dressing’ of the previous decade saw its contrast in the ‘dress down Fridays’ of the 1990s, which were better suited for going to a ‘gastropub’. The worry was about increasing ‘cybercrimes’, ‘spam messages’, and the ‘millennium bug’.

While that particular bug did not hit the new millennium, the ‘tsunami’ did. ‘Global warming’ became a concern and people became aware of their ‘C-footprint’. ‘Alpha moms’ took charge of their children’s futures, while soldiers and ‘embedded journalists’ moved to the new theatre of war, ‘AfPak’. The UK, meanwhile, did a ‘Brexit’.

This millennium has moved at a fast pace, with scientists agreeing that the age of the ‘anthropocene’ needs to be defined. Meanwhile, the world got busy ‘unliking’ and ‘retweeting’ social media posts, most of which were annoying ‘selfies’, always appended with ‘trending hashtags’. All this has created so much ‘e-clutter’ that even ‘cloud computing’ is finding it difficult to handle it. No wonder people are putting useful content behind ‘paywalls’. There have been so many terror attacks that people were having ‘threat fatigue’. Yet, no one was prepared for the ‘corona tsunami’, though they are somehow managing to navigate these uncharted waters, with a new vocabulary being one of the surviving aids.

What will be the lasting impact of this pandemic on our vocabulary? Will this new language find usage even after the virus has weakened? Or, will, having served its purpose during an extraordinary time, the new lexicon get forgotten till it is needed again? Only time and the ‘coronnials’ will be able to tell.

The staying power of the new vocab is not such a concern anyway, we are more worried about the staying power of the virus.