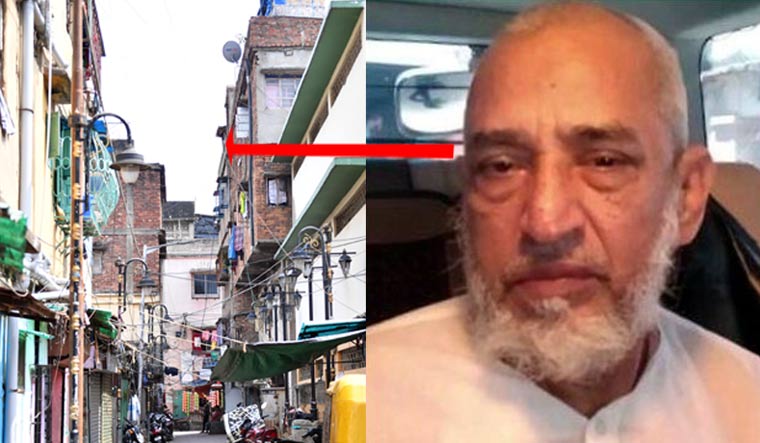

For his neighbours, Ahmed Ali was master moshai, known for his proficiency in English, Urdu and the Quran. The soft-spoken 71-year-old used to teach students in the neighbourhood. He also used to lend money, at exorbitant interest. But he chose to keep it private, just like his rented apartment in Bedford lane, a central Kolkata locality with a significant Muslim presence, where he lived with his wife, Zareena, and their 10-year-old daughter.

“A long curtain always covered the gate,” said Safiq Ul Rahman, Ali’s landlord. “The door was always closed. Even I could not go in, although the house was mine. But he always paid the rent on time.”

Ali, who had been living in Kolkata since 1996, went missing from his house on February 21. Two weeks later came reports about his arrest in Bangladesh and the shocking revelation that he was Abdul Majed, a retired major in the Bangladesh army. He was wanted in Bangladesh for the assassination of Sheikh Mujibur Rahman, revered as the father of the nation. He was executed on a long-pending death warrant on April 12.

For decades, Bangladesh has been doggedly pursuing six of its former military officers—Captain Abdur Rashid, Major Shariful Haq Dalim, Lieutenant Colonel Noor Chowdhury, Lieutenant Colonel Rashed Chowdhury, Lance Naik Moslem Uddin and Major Abdul Majed—implicated in Mujib’s assassination. Majed had been on the radar of intelligence operatives from India and Bangladesh for a while because of his trips to the US to meet his son from his first marriage and also for his frequent telephone conversations with his tainted colleagues.

The sleuths moved in on February 21, reportedly without the knowledge of the West Bengal government and its intelligence apparatus. CCTV footage showed a five-member team picking up Majed in the morning. After extensive interrogation in Delhi, he was sent to Dhaka. There are reports that Moslem Uddin, too, has been picked up from West Bengal.

By helping Bangladesh nab two of Mujib’s killers when the country celebrates his birth centenary, India has taken a big step in repairing bilateral ties which have come under considerable strain after the abrogation of Jammu and Kashmir’s special status and the passing of the Citizenship (Amendment) Act.

Following Majed’s execution, a Bangladesh cabinet minister said Prime Minister Narendra Modi completed work left unfinished by Indira Gandhi. “The way he handed over the two fugitives will be recorded in history,” said the minister. Interestingly, India has remained silent about the whole process.

Majed’s execution, however, has come as a rude shock to his family and friends in Kolkata. “We had no clue about his past. He was a polite man who used to pray five times a day,” said Zareena’s brother Nazeemuddin Mullick. “A local lawyer brought us his proposal around ten years ago. After meeting him, we agreed to the marriage, although he was 30 years older than Zareena. My sister never had any complaints about him.” It was Zareena’s second marriage as well. Mullick said Zareena and her two daughters—she has a daughter from her first marriage, too—were in deep trouble. “We have written to the chief minister for monetary help. My sister is bedridden and has become mentally unstable,” he said.

Mullick said Majed was a gentleman, but he used to get irritated when asked about his past. “He looked like someone with a military background,” said Mullick. Majed, who had always kept a low profile, started getting noticed after he played an active role in the anti-CAA protests. He had also established himself as a committed worker of the Trinamool Congress.

Majed was on good terms with the CPI(M) as well. He moved to Kolkata in 1996, after Mujib’s daughter Sheikh Hasina came to power in Bangladesh. At the time, the CPI(M) reigned supreme in West Bengal. He even managed to get a ration card in the below poverty line category. He switched his allegiance to the Trinamool Congress after Mamata Banerjee came to power in 2011. “In the past decade, he got everything, thanks to the local leadership of the Trinamool Congress,” said Sajjad Hossain, a local trader.

When Majed came to Kolkata, he was forced to stay in one the most backward areas of Kolkata, where the streets were always full of garbage. “Only poor Muslims from Bihar used to stay there. Today, things have changed, but the area is still known as a settlement of impoverished people,” said social activist Shansha Jahangir.

Majed was forced to endure such indignity after Hasina decided to hunt down her father’s killers. After losing his job as Bangladesh’s defence attache to Libya, he fled to Thailand. From there, he found his way to Kolkata, which was, by then, a well-established refuge for exiled Bangladeshis. When Hasina lost the elections in 2001 to Begum Khaleda Zia, Majed briefly went back to Bangladesh. He stopped going after Zia was voted out of power in 2006.

Like Majed, Moslem Uddin, too, had sought refuge in India. While Majed chose the slums of Kolkata, Moslem Uddin went to a border village in the North 24 Parganas district where he worked as a quack and ran a pharmacy. According to sources, Majed gave up Moslem Uddin’s whereabouts during interrogation. Bangladesh has confirmed that his identity is being verified and he, too, could soon face the death penalty.

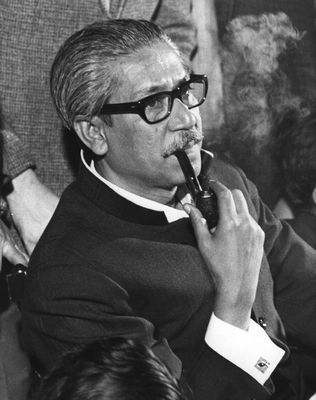

Mujib was only 55 when he was assassinated. A retired army officer said the rebel officers were initially not keen on killing the president. “He was given multiple options to save his life, including a chance to resign,” the officer said. “But being a mass leader, he chose to fight back. He threatened to call the Indian prime minister. Subsequently, the officers decided not to take any chances and shot him and most of his family members.”

The entire operation was planned by Rashid and Major Farooq Rahman. Apart from the military angle, the assassination, which took place on the morning of August 15, 1975, also involved political and diplomatic operations. Awami League MP A.K.M. Rahmatullah, who was a student leader at the time, said Mujib’s cabinet colleagues like Khondaker Mostaq Ahmad, who became president for a brief period after the assassination, helped the military. Army vice chief General Ziaur Rahman—Begum Khaleda Zia’s husband, who was president from 1977 to 1981—too, joined the plot because he was miffed with the elevation of his junior officer K.M. Shafiullah as army chief. The United States also allegedly played a key role, with CIA station chief Philip Cherry being kept in the loop by the army.

The army was out on the streets by late night on August 14, but nobody was bothered because Mujib had declared a national emergency to counter the demonstrations organised by extreme left groups against the government’s handling of the famine of 1974. Many observers feel that Mujib’s idea to go ahead with a one-party system was a major reason behind the army’s decision to remove him. Rashid told the marching soldiers that the army and the top political brass wanted to finish the “autocratic regime”.

It was Noor who fired the bullets that killed Mujib. He was later made lieutenant colonel and was posted abroad as high commissioner to Hong Kong and ambassador to France. He now lives in Toronto under the protection of the Canadian government.

Barring Rashid, Dalim, Noor, Rashed, Majed and Moslem Uddin, the rest of the conspirators were captured and executed between 2000 and 2010. Majed’s execution and Moslem Uddin’s reported capture have spurred Bangladesh missions abroad to nab the remaining four.

Speaking exclusively with THE WEEK, Bangladesh’s Minister for Liberation War Affairs A.K.M. Mozammel Haque said Majed could be executed only because of India’s help. “Moslem Uddin is in Indian custody, and his identity is being verified. Noor is sheltered by Canada and Rashed by the US.” He said the remaining two—Rashid and Dalim—could be in India or Pakistan.

Dalim had served at several Bangladeshi missions in the Middle East. When Bangladesh established diplomatic ties with Pakistan, Rashid was posted there. Now retired, he runs businesses in Kenya, but he reportedly stays in Pakistan. Dalim, who runs petroleum businesses in many countries, too, lives in Pakistan, according to intelligence reports.

Haque said Mujib’s assassination was an international conspiracy orchestrated by Islamabad. “All those officers were trained in Pakistan and had links with Pakistan army institutes,” he said. “Pakistan had a direct role in the assassination of the father of our nation. And, they had the support of many western countries.” Hasina has written to President Donald Trump and Prime Minister Justin Trudeau for their support in extraditing Rashed and Noor. While Noor’s case is going on in Canada’s immigration court, the US has so far refused to hand over Rashed.

Noor leads a lonely life with his wife, after having stopped interacting with the local Bangladeshi community. “During a function five years ago, one man walked up to him and slapped him several times. He stopped socialising after that incident,” said Sajjad Rahman of the Canadian Bangladesh Centre.

Noor refused to respond to THE WEEK’s queries. His lawyer Barbara Jackman said Noor wanted to be left alone. “He is very much saddened. He does not want to be disturbed,” she said. Noor’s extradition battle has affected diplomatic relations between Canada and Bangladesh. “I am fighting in the court on his behalf. So, please do not ask me to reveal the details. It might jeopardise his case,” said Jackman.

Rashed, however, travels across the US to take care of his business interests and is said to be close to several key politicians. Trump wrote to Hasina in April to wish her on Mujib’s birth centenary and called the former president a global icon, but he has so far refused to respond favourably to the extradition request.

“We can understand Pakistan’s lack of commitment, but we have failed to understand the role being played by the US and Canada,” said Haque. “What would have been their reaction if we sheltered the assassin of an American president or a Canadian prime minister? Their logic is that death sentences are inhuman. But what about the murder of a head of state? Western leaders refuse to see what these people did and how they killed the entire first family of our nation, except for two people.”

With one retired officer getting executed and five more in the line, there have been some concerns in Bangladesh about the army’s response. Information Minister Hassan Mahmud said the country was united on the issue. “Mujib’s killers are the most hated people in Bangladesh,” he said. “There is no hue and cry over the hanging of his murderers. We are confident that we will be able to bring all those criminals to justice.”