THE CHEETAH WENT extinct from India around the time the country got independence. Now, if all goes well, it could be spotted again around the 75th year of independence. With the Supreme Court having cleared the decks for introducing cheetahs into India on an experimental basis, officials are upbeat. They say that once a home has been set up, the first batch could be imported from Africa in 18 months, even as sceptics wonder at the feasibility of, or even need for, such an expensive programme.

M.K. Ranjtsinh, former director, wildlife preservation, and Dhananjai Mohan, chief conservator of forests, Uttarakhand, will assist the government and the National Tiger Conservation Authority to implement the project.

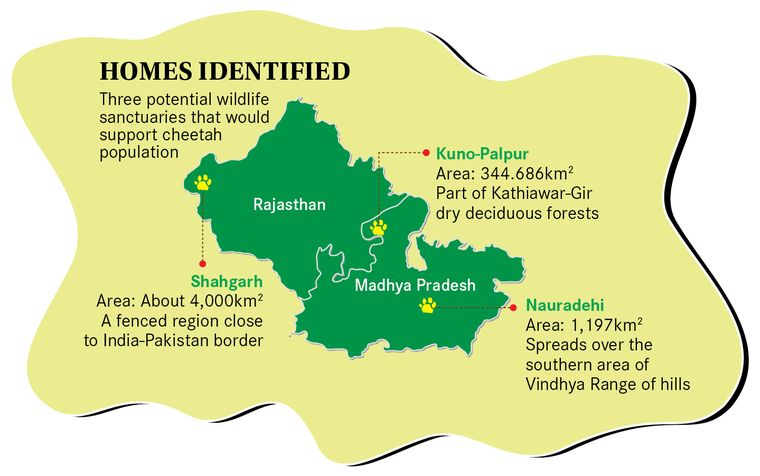

Yadvendradev V. Jhala, dean and scientist, Wildlife Institute of India, said that the first step will be the reassessment of the sites—Kuno-Palpur and Nauradehi in Madhya Pradesh, and Shahgarh in Rajasthan—identified for cheetahs.

At Nauradehi, 20 villages were relocated from the core area and the compensations were paid at Project Tiger rates—Rs10 lakh per adult member in every family. Kuno-Palpur, on the other hand, had already been cleared for introducing Asiatic lions from Gujarat—a plan which fell through. After an investment of Rs20 crore on clearing out the area, it will be a waste if it is not used for some wildlife programme.

The next step will then be to secure a population of cheetahs from Africa. The cheetah which was hunted into extinction from India was the Asiatic cheetah (Acionyx jubatus venaticus). Iran, the only place which has Asiatic cheetahs today, is down to its last 30. So, the only choice left now is to get the African cheetah (Acionyx jubatus jubatus), a different sub-species, and the Supreme Court emphasised that this programme could, therefore, not be called a “reintroduction”. At the time when the proposal had been mooted a decade ago, officials had identified Namibia for importing cheetahs.

Procuring the animals is the least of the expenses. Officials say that the purchase should not cost more than Rs10 crore for 20 animals. They are also hopeful that some cheetahs might come to India as gifts, given the new push in India-Africa friendship. Getting the habitat ready, however, is another story altogether. Low survival rates of cubs is an issue with cheetahs. Animal-human conflict is another issue.

A good species introduction programme requires at least 40 individuals, though 20 is the minimum number. It is likely, however, that not all cheetahs will be brought in together. The officials could try a first instalment of two males and four to six females; then depending on the success, more individuals could be introduced.

The introduction into a new home is a gradual process. Initially, the animals would have a “soft release” into an enclosure of natural vegetation, so that they de-stress and get over the homing instinct. In fact, they could initially be fed on carcasses till they establish in the new home.

The cheetah’s extinction is an emotive issue for India. It has gone extinct solely because of hunting by humans. The animal, which gets its name from the Sanskrit word chitraka (which means the spotted one), once roamed over vast swathes of the land, from the Terai belt in the north to as far south as Karnataka. The last were shot by the Maharaja of Surguja in 1948, though the last sighting of a female cheetah was in 1951.

“The cheetah is a part of the country’s culture and history, it needs to be remembered,” said Jairam Ramesh, who, as environment minister, had made a forceful bid to get cheetahs. Bringing back the cheetah has always been part of wildlife conversation projects, even though nothing worked out so far. In the late 1970s, then prime minister Indira Gandhi had spoken to Iran about exchanging our lions for their cheetahs. Iran then had 250 cheetahs and could afford to exchange. The plan flopped.

The recent order of the court, interestingly, is a turnabout from its 2013 decision, when it saw no merit in getting cheetahs from Africa, while there were more pressing wildlife concerns like a new home for Asiatic lions and rescuing from extinction animals like the dugong, Manipur brow-antlered deer and great Indian bustard. At that time, the government wanted to get cheetahs into the Kuno-Palpur forests, which had been cleared as second home for Asiatic lions—a programme that was fizzling as Gujarat was loath to part with its USP.

The order is time bound; the court expects an initial progress report by the expert committee in four months, and at an interval of four months subsequently. The naysayers have a host of doubts, starting from available habitat to the need for bringing in an exotic species that never roamed these lands. Former Project Tiger director P.K. Sen, a fierce opponent of the project, points out that Kuno-Palpur, cleared as a scrubland, has grown trees over the years, and is not ideal for cheetahs. “Cheetahs were hunted to extinction by the Maharajas for sport, now erstwhile royalty wants them back for sport. Even if we get cheetahs in India, what conservation role will they serve?” he asked.

The cheetah lobby is as emphatic. “The cheetah is not like the dinosaur, which disappeared millions of years ago,” said Jhala. “We still have memories of this animal here. As for the African variety being exotic, the two cheetahs were as different as people in Spain and Germany are. Yellowstone National Park in the US got back its wolves, we should get the cheetah, too.”