Stand-up comic Ritu Chandra cannot forget the ferocity of the attack, even after a year. Chandra and a friend were walking her dog at Columbia Park in Berkeley Heights, New Jersey—as she had done for the past 14 years—when an older white woman charged at them, shouting obscenities. “She just screamed at us,’’ said Chandra, recollecting the incident that happened on July 17, 2021. She had the presence of mind to whip her phone out and record the attack. The now viral video shows the woman shouting, “You f**king c***k bi**h’’ and trying to grab something out of her pocket. It shows a glimpse of the increasing vitriol directed at Asian Americans across the US.

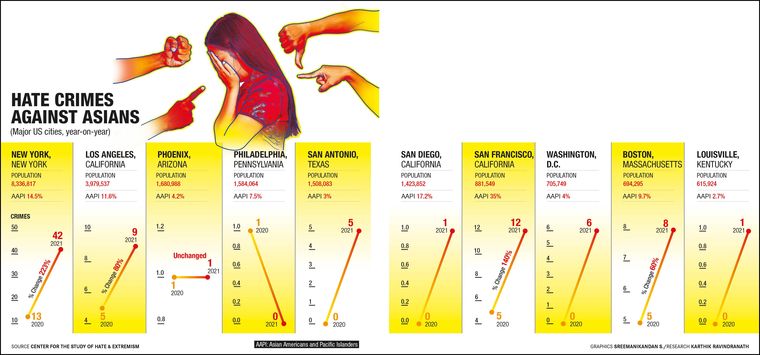

Data compiled by the Center for the Study of Hate and Extremism (CSHE) at the University of California, San Bernardino, shows a 339 per cent increase in anti-Asian crime last year compared with the year before. Cities like New York, San Francisco and Los Angeles have seen a sharp spike. “It is definitely real and rising,’’ said Kani Ilangovan, who leads Make Us Visible NJ, a group fighting for the stories of Asian Americans to be included in the school curriculum. “In New Jersey, hate crimes against Asian Americans have skyrocketed by over 80 per cent during the pandemic. According to Stop AAPI Hate (a non-profit organisation which tracks hate crimes against Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders), one in three AAPI parents report that their child experienced a hate incident at school in the past year,’’ said Ilangovan. The most visible hate crime happened on March 16, 2021, when a gunman shot and killed eight people in Atlanta. Six of the victims were Asian women.

President Joe Biden has expressed concern about the rise in hate crimes. Last year, he signed bipartisan legislation targeting hate crime, especially against Asian Americans. “Hate has no place in America,’’ he tweeted, signing off on the bill. Biden hosted a summit at the White House against hate crimes on September 15, bringing together local leaders, experts and survivors. “It is so important that we keep hollering,’’ he said. “It is so important for people to know that is not who we are.’’

There has been a steady rise of hate crime against Asians from the time the pandemic started. A 124 per cent jump in hate crimes were reported in 2020 compared with 2019, according to the CSHE report. New York, San Francisco and Los Angeles are the leading offenders. The situation is not much different in other cities as well. Lakhwant Singh was attacked viciously by a customer in his store in Lakewood, Colorado, in April 2020. Eric Breemen walked into the store, damaged several items and told Singh and his wife “go back to your country’’. Singh went outside to take a picture of his licence plate and Breeman rammed his car into him, throwing him across the parking lot.

In March 2020, the Chinese for Affirmative Action, the AAPI Equity Alliance and the San Francisco State University’s Asian American Studies department launched the Stop AAPI Hate Reporting Center. In the first week itself, it got 600 reports. Within a month, the number went up to 1,500. A report released two years later, which documented 11,500 incidents, makes for grim reading.

“This number is just the tip of the iceberg,’’ said the report. The nationally representative report found that one in five Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders experienced a hate incident in 2020 or 2021. The most vulnerable groups are women and children. In 2021, the Stop AAPI Hate clocked 4,533 incidents till June. Nearly two-thirds were instances of verbal harassment. And there seems to be no let up even as life returns to pre-pandemic normalcy. Four Indian American women were racially abused by a Mexican-American woman, Esmeralda Upton, in Dallas, on August 24. “I hate you f**king Indians,” said Upton, who asked the four Indian Americans to go back to India.

“I have experienced racism before,’’ said Chandra. “But it was quieter.’’ She spoke of a time when she went to check out an apartment, but was politely told that it had been taken. The next day, Chandra asked a white friend of hers to show interest in the apartment, and she found out that the reason she did not get the apartment was that she was brown. “After Donald Trump became president, there were no consequences [for racist behaviour]. People felt empowered to use racial slurs,” said Chandra.

Now, in the post-Trump, post-truth pandemic era, the situation remains grim. “There definitely has been a surge of xenophobia and discrimination that has targeted Asian Americans, driven at least in part by pandemic-fuelled racism,’’ said Sim J. Singh Attariwala, senior manager of policy and advocacy at the Sikh Coalition, a community-based organisation. “It is difficult to say how much of that includes or drives anti-Sikh hate, but we know from the data gathered by the FBI that anti-Sikh hate crimes are generally on the rise as well, and that Sikhs are consistently among the top five most targeted religious groups.”

But just documenting hate crimes is not enough. The road to justice, or even acknowledgement, is not easy. Lakhwant chose to contact the Sikh Coalition to pursue his case, and hate crime was added to the charges against Breeman. For Chandra, it was different. The incident might have been pursued by the police as a hate crime, but the local prosecutor chose to ignore the charge, saying “it was not the right racial slur’’ to make the case. “It is like saying she was a dumb racist,’’ said Chandra, “as if that made it less of a violation.”

Chandra is still trying to live with the lack of justice. “I feel I am being treated unfairly,’’ she said. “I have been told that this country is about equality. When you find out that you have been disregarded, it is infuriating. I knew I was going to fight.”

She, however, is not alone. The rise of hate crimes against Asians has shown the victims that resistance is not only about fighting for stricter laws or action, but also about ensuring that their stories are told. Make Us Visible NJ aims to do just that. Founded in January 2021, Make Us Visible, which began as a collaboration of two parents and a teacher, intends to go beyond documenting hate crimes. It strives to find a way to counter hate crimes by focusing on inclusion rather than on differences. The group has successfully lobbied for the passage of the AAPI Curriculum Bill which mandates that NJ students in grades K-12 will learn AAPI history and contributions.

“I was born here,’’ said Ilangovan. “This is my homeland. It is really heartbreaking that there are some people who have been here for five generations, but are still treated as foreigners because of how they look. I want my children to feel safe in this country. This is their home.”

The first step is to ensure that their contributions do not remain invisible. “This project shows our belonging,’’ said Ilangovan. “There are so many civil rights successes that are from Asian Americans. The ability of girls to play sports in school, the labour rights movement, civil rights and so many different things Asian Americans fought for. But people don’t know these things.”

In New Jersey, where hate crimes have been rising steadily for the past three years, it is all the more important as the demographics are changing. The recent census showed that 11 per cent of the population in the state is now Asian American. In Jersey City, the number is even higher at 28 per cent. The only way the next generation will be able to fight hate crime is if they find themselves represented in their books. “In my own school district, majority students are a minority,” said Sima Kumar, an educator with Make Us Visible NJ. “The demography of students is changing and the curriculum needs to keep up with these changes to reflect the experiences of students of colour.’’