ROBERTO CINGOLANI was frazzled at the end of the energy and environment ministers’meet of G20 countries this July. Cingolani, who is Italy’s ecological transition minister, had chaired the two-day meet. He said that negotiations with India and China were particularly tough and that the group failed to agree on a common language for their document ahead of the Conference of the Parties (COP) Summit to be held in Glasgow.

The G20 is a group of the world’s top 20 economies and therefore is a grouping that best reflects modern-day realities. Most other important groupings do not give representation to emerging nations like India. The failure of the G20 ministers’ summit to arrive at a consensual vocabulary may have been a disappointment to Cingolani, but his comment that India is a tough negotiator is a backhanded compliment. India is putting up a tough resistance to the bullying by advanced nations, as it seeks out space and carbon budget for its development. The advanced nations, having reached saturation levels of energy consumption, are now preaching to developing nations to cut down on consumption, reduce the use of coal and raise their climate mitigation ambitions. The buzzword these days is net zero, which effectively means to reach a stage when the amount of carbon dioxide captured from the atmosphere is equal to or more than the amount of greenhouse gases emitted, thus nullifying temperature rise.

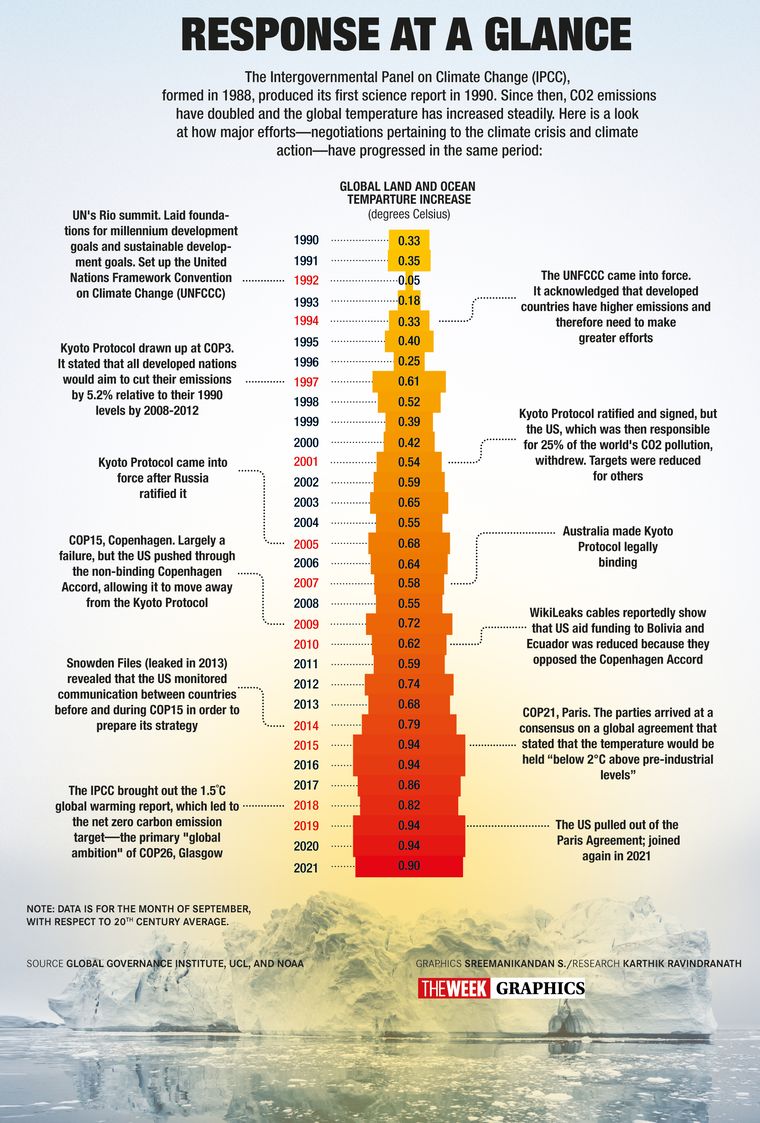

The problem with this lofty ambition is that countries which have polluted for a century and a half are now reading the riot act to nations that have barely got out of poverty. Also, it is against the common but differentiated responsibility (CBDR), an ideal agreed to at Paris five years ago, which meant that different nations have varied levels of responsibilities towards climate change mitigation. In effect, it should be the developed world which should do more—emit less, put in more money into mitigation and relief, and also help their poor cousins with technology solutions. They have not done this, at least not to the level required.

For India to hold its own in the big bad world of bullies, it requires a team that is tough, and has done its homework well. Richa Sharma, additional secretary in the ministry for environment, forest and climate change, is the leader of this 15-member team that is bracing for a tough fight in Glasgow, for every little space for development and every sliver of carbon budget allocation, while ceding as little ground as possible. Sharma led the negotiations in Italy, too, and was largely responsible for Cingolani’s dismay. India refused to agree to put a deadline on phasing out coal. It will remain the mainstay of India’s energy requirement. India also refused to change the language around the 1.5 to 2 degree temperature rise. At the Paris summit, the agreement was to keep rise in temperatures below 2 degrees, preferably below 1.5; some countries now feel they should raise the ambition. India feels there is no need to shift goalposts without meeting previous commitments first.

An alumna of Delhi University, Sharma has been an achiever throughout, winning gold medals at both her BA and MA levels. She majored in psychology, which has, perhaps, helped her deal with team members and opponents. An officer from the Chhattisgarh cadre, Sharma joined the environment ministry in 2019, and has been in the negotiations team for climate change, steering the domestic climate change agenda and strengthening international cooperation at multilaterals like BRICS (Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa), SCO (Shanghai Cooperation Organisation) and G20. She took over as lead negotiator earlier this year.

Officers who have worked with Sharma say that though she is not a harsh taskmaster, she knows how to get the work done. She goes into the minutest details, said a colleague, and is quick to respond with such logic and clarity of thought that it leaves the opponent baffled and team mates impressed. Sharma also has the knack of developing a working rapport with other negotiating teams, be it the Chinese, with whom India has many common issues as well as divergences, or the Americans, who are now chanting the net zero mantra. In the last two years, she has carved her space in the negotiations stage and is a known face.

Sharma will lead a heavy duty inter-ministerial team of experts, which includes J.R. Bhatt, scientist from the environment ministry, climate change finance specialist Rajasree Ray and joint secretary Neelesh Kumar Sah.

Although she has kept herself away from the limelight, Sharma interacted with THE WEEK. “At COP26, India will lead from the front as a responsible nation that is undertaking tremendous domestic climate actions as well as fostering international collaboration,”she said. “India will make constructive contributions in negotiations regarding pending agenda items (from the Paris Agreement) while respecting the principles of the UNFCCC (United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change) and Paris Agreement.”

Negotiations are a taxing job. Sometimes, one has to cede ground owing to other compulsions. This happened in Paris, when India wanted two words—historical responsibility—in the final document, which would make it official why the developed world needed to do more to address climate change. These countries were naturally opposed to it, and negotiations had reached a dead end. That is when US president Barack Obama made that famous call to Narendra Modi and India withdrew its stance. In return, India received much support for its proposed International Solar Alliance, from both the US and a grateful host, France.

In the world of diplomacy, you win some, you lose some. But fight, you must.