AT THE HEART of any communist political system is the Marxist emphasis on class struggle, with the apparent objective of achieving a society of perfect equality, a society free from want. But the class struggle itself depends on economic conditions. It is, therefore, not without reason that heads of communist nations have a constant focus on the economy, never mind the effectiveness of their prescriptions.

Since the end of the Maoist era, China’s leaders have been more careful than their counterparts in the former Soviet bloc countries in giving economic growth its due place. They have succeeded in shaping a successful economic model that has delivered high rates of growth for decades. They have understood the consequences of economic conditions for a country’s domestic politics and its international prospects better than most.

Indeed, Chinese leaders consider it a necessary part of their skillset to have a detailed knowledge of the latest economic developments, both at home and abroad. In fact, it is usually impossible to reach the top echelons of the Chinese leadership without considerable experience in economic administration—some provinces in China have GDPs as large as that of certain developed economies.

The constant interplay of the political with the economic is an important feature of the Chinese economy, something that can often be ignored by casual observers.

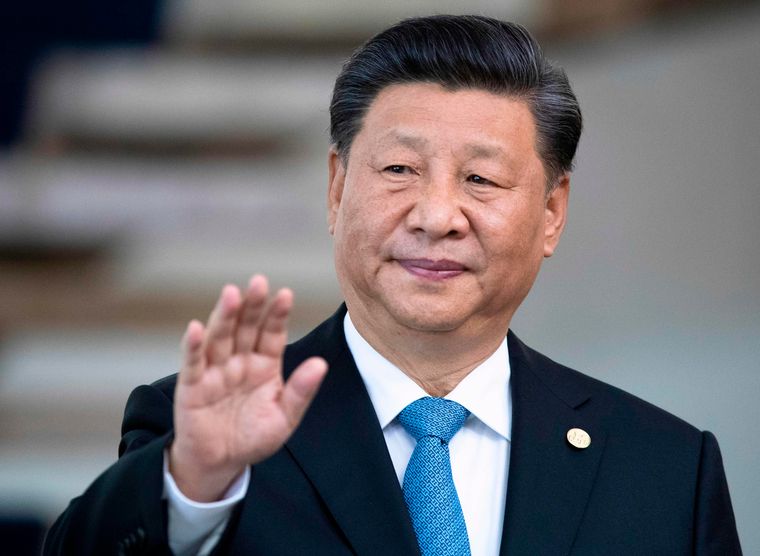

When the Communist Party of China (CPC) General Secretary Xi Jinping, who also serves as the country’s president, says that China is a champion of globalisation, it is easy to view the statement purely from an economic standpoint. This would, however, be an entirely wrong approach to take. While it is true that China has gained much from globalisation and hopes to gain still more from it, its approach to globalisation is a one-way street. It has sought to attract global capital and high tech to its shores, and, in turn, deploys its capital and tech abroad.

China, however, has also been mercantilist in its approach, subsidising companies operating in its jurisdiction with free infrastructure and low-interest loans and other forms of hidden subsidies in contravention of the World Trade Organization rules, while keeping its own economy closed with non-tariff barriers such as difficult legal requirements that undermine foreign entities trying to compete with local Chinese manufacturers.

The Americans have only recently woken up to this reality of the Chinese policy in which decoupling from the US economy has long been the objective. For instance, American tech companies and their products like Google, Facebook and WhatsApp have been banned in China for years.

India is another victim of this Chinese behaviour as both its persistent trade deficit with China and the high number of anti-dumping cases it brings against that country at the WTO show. Even in sectors where India is competitive, such as pharmaceuticals, it has taken great effort by the Indian government for its companies to enter and that, too, only because the Chinese wanted to make medicines cheaper for their own public healthcare system.

This brings us to an important issue that has been at play in recent months and years in China. Why has the CPC actively targeted successful enterprises and sectors? Jack Ma of the Ant Group, one of China’s most internationally well-known entrepreneurs, was prevented from launching an IPO worth a record $37 billion in 2020. Earlier this year, Beijing began a crackdown on sectors as varied as coal and edtech.

Ma had complained about China’s regulatory system at a major meeting in Shanghai, with top political and economic leaders in the audience, saying China was stifling innovation and that its banks had a “pawnshop”mentality. The Communist Part of China’s (CPC) response was only to be expected.

Under Xi, it has been very clear that “party, government, army, the people and intellectuals—east, west, south, north and centre, the party leads everything”. This Maoist-era slogan makes no allowances for private enterprises, no matter how big or important they are in the eyes of the rest of the world. Ma, himself a CPC member, was brought down because he dared to criticise the party, forgetting that he owed everything to it creating and maintaining the conditions for his growth and prosperity. Other major tech giants have also been put on notice.

This then brings us to another important question: how ‘private’is the private sector in China?

In 2017, it was reported that some 70 per cent of China’s privately-owned companies had party organisations attached to them; under Xi, the CPC has specifically targeted private enterprises aiming to increase its ideological work and influence. This then has implications for Indian companies with any Chinese investments, especially in e-commerce and fintech, both of which are sensitive from the point of view of data security and privacy issues.

The CPC has an increasingly expansive definition of its legal remit to monitor, supervise and punish—even across China’s international borders. Under such circumstances, for Chinese investors, the CPC’s writ will always take precedence over the laws of the country where they operate, or even international laws. Chinese capital will, thus, come with strings attached.

The attack on China’s edtech sector has been interpreted as part of the CPC’s efforts to regulate malpractice in the industry. It is seen as part of the wider crackdown on big tech in an effort to impose ideological order in the sector. In September, the Chinese government released new guidelines for “Strengthening the Construction of the Online Civilisation”. This appears to be an outgrowth from another Maoist-era catchphrase, namely, “spiritual civilisation”, and an attempt to ensure order and ideological standards as mandated by the CPC. In India, we might consider this the equivalent of what is known as “moral policing”.

According to one estimate, as much as 44 per cent of China’s industrial activity has been affected by massive power shortages with power rationing in place in 17 of China’s 31 provinces. While there are multiple reasons for the situation—with coal shortages and high fuel prices from expanding post-pandemic industrial demand among them—the fact is that even in this case, the situation has been exacerbated because of political considerations.

Xi had announced at the United Nations in September 2020 a commitment to achieve carbon neutrality by 2060. Since then, there has been pressure on China’s local and provincial governments to reach their energy reduction targets set by the central government annually. Thus, local authorities have simply cut power and told industries to shut down to make sure they meet political expectations from the centre.

The power crisis highlights another important trend in today’s China, namely the centralisation of power that is taking place at multiple levels in the party-state. The most visible and obvious form of centralisation is that of power within the CPC in the person of Xi. Another form of centralisation is of power and authority from the provinces and regions to Beijing, while a third form is of the privileging of state-owned enterprises at the cost of private enterprises.

These forms of centralisation give a sense of not just the factors that made China successful in the past four decades, but also of the problems that cropped up from time to time that China’s leaders today are struggling to deal with.

It was precisely the expansion of the freedom of speech under Deng Xiaoping, the decentralisation of power to the provinces and the capital that flowed to private enterprises over time that powered China’s rapid economic growth over decades. These reforms and freedoms—despite brief crises like the Tiananmen Square crackdown in 1989—put China in a place by the end of the last century from where it could begin accruing political power and influence on the global stage to go with its economic strength.

But as with all things in authoritarian states, abuse of power, overexploitation of resources and ignoring of the greater common good followed and spiralled out of control. China in the 2000s was also a site of multiple protests over various issues ranging from ethnic discrimination to labour rights to environmental degradation. It is into this cauldron that Xi walked in as the new general secretary of the CPC in late 2012. And like all leaders before him, he sought to use China’s domestic and external capacities to strengthen what seemed to be the increasingly shaky foundations of the CPC itself and he has more of both kinds of capacities than any of his predecessors.

There is a reason why China is called a party-state: the People’s Republic of China is first and foremost devoted to preserving the CPC in power and is only secondarily concerned about questions or issues that we would normally understand as ‘national interests’.

So, China’s aggressive and uncouth diplomatic behaviour across the world, now termed ‘wolf-warrior diplomacy’, might not make any sense from the perspective of a country trying to create a good impression of itself and to achieve its interests in other countries. It does, however, make a great deal of sense from the perspective of a party trying to remain in power by portraying itself as the best possible defender of not just China’s territory and sovereignty, but also of its image and its supposed civilisational greatness. In other words, Xi has simultaneously used a mix of nationalism and state capacity to rouse the ordinary Chinese and also to suppress them to strengthen the party.

Those of us watching in India will find some of this familiar in the choice of language and actions the BJP uses in portraying itself as a distinctly better defender than other political parties of India’s interests and pride at home and abroad. Thus, what we are seeing both in authoritarian China and populist regimes elsewhere in the world is the conflation of regime interests with national interests.

Meanwhile, the way Xi has gone about the task has left him open to charges that his ruthless anti-corruption campaign—as much an economic necessity as a political one—has been both selective and incomplete. He has also in the process clamped down on what limited civil rights and media and academic freedom that existed in China. Indeed, that Xi has had to do any of this at all should itself be a comment on the failings of the Chinese political system.

The CPC leadership understands this reality, including the fact that centralisation of power can only be one approach to tackle China’s many ills. The party has understood that it is equally important to provide an intellectual rationale to the watching public for this centralisation of power and the increasing dominance of the party in their daily lives, so that political challenges can be prevented or pre-empted.

Nationalism by itself is not sufficient for this purpose or at the very least needs to be tempered so that it can be controlled by the CPC. Xi and the party have, therefore, followed up with a regular stream of slogans and concepts pitched at both popular and elite levels explaining the nature, objectives and rationale of the centralisation of power. Thus, Chinese politics today is suffused with such expressions or targets with economic imperatives as ‘poverty alleviation’, ‘rural revitalisation’, and ‘common prosperity’. Aligned to these economic goals are more obviously political goals as ‘national rejuvenation’or to ‘forever walk at the party’s side’.

Together, these phrases and the effort that goes into showcasing and achieving the goals they represent confirm the close interlinkages between economic performance and political legitimacy of the CPC. They also underline the fact that in China, it is always politics that drives the economy.

—The author teaches at Shiv Nadar University, Greater Noida, Uttar Pradesh