Two days after the Easter-day blasts, the streets of Colombo are eerily silent. As night falls, policemen walk the streets looking for suspicious strangers. Curfew and fear have gripped the city.

At Colombo 13, the road to St Antony’s Shrine is deserted, though a few shops are open. The Catholic shrine was one of the three churches attacked by suicide bombers on the morning of April 21. A clock on a wall near the shrine reads 8:45am. “It shows the time we heard the explosion,” says Yogaraja, a 42-year-old who lives nearby. “All of us here are like one community—be it Muslims, Hindus, Christians or Buddhists. St Antony is our saviour in this part of Colombo. He will not spare the wrongdoers.”

Around 40 kilometres north of Colombo, the seaside city of Negombo is still grappling with shock and grief. Scores of believers were killed by the blast in St Sebastian’s Church; its floor covered by flesh, blood and fragments of stained glass.

A giant canopy has been erected near the damaged church. Under it, mourners sit on chairs placed on the sandy ground. After the prayers, pallbearers make their way through the crowd. Loud cries fill the air as the mass burials are held.

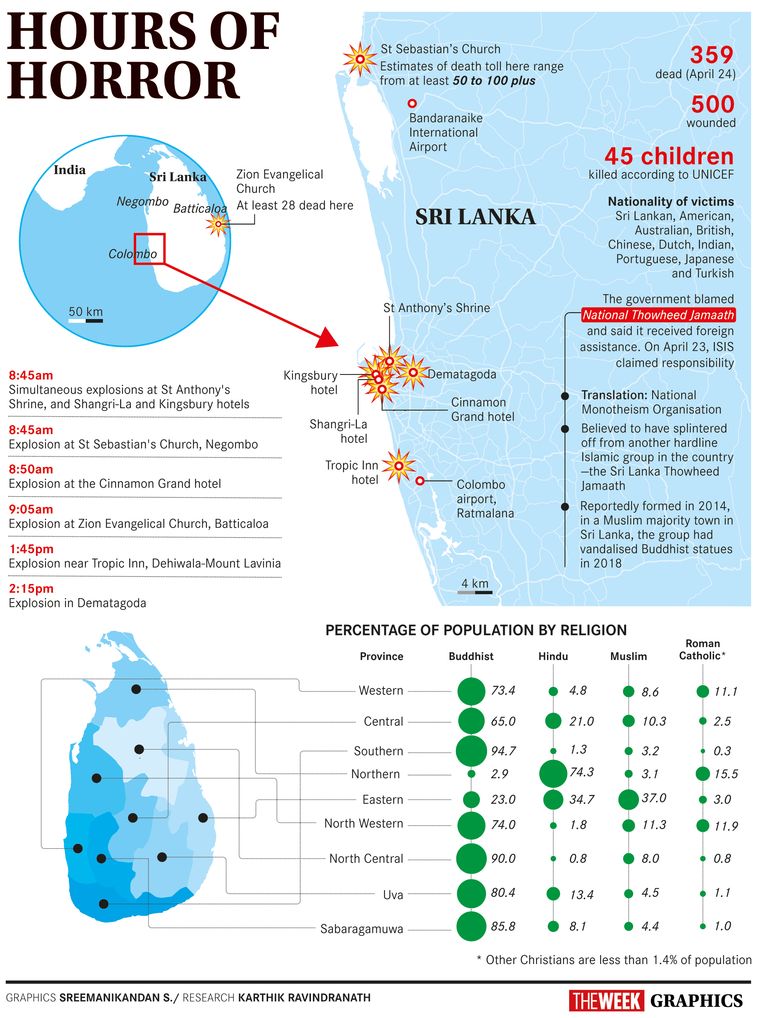

The blasts targeted three churches and four hotels in Colombo, Negombo and Batticaloa, a city in Sri Lanka’s Eastern Province. More than 350 died and around 500 were injured. A national emergency has been declared, and life has come to a standstill. “We never expected that we would become the target of such deadly attacks,” says Fr Lour Fernando of St Sebastian’s Church. “People are afraid. But we will have to remain strong and keep praying.”

The blasts have pushed Sri Lanka back to its history of conflict and polarisation. Security personnel can now detain suspects without a court order, a special power that was last exercised in the civil war that ended in 2009. With tensions simmering between communities, a decade of peace seems to have come to an end.

Sri Lanka’s Christians, who make up 7 per cent of its 22 million people, had largely been spared the ravages of war. They were also thought to be insulated from the recent tensions between Muslims and right-wing Buddhists.

Prime Minister Ranil Wickremesinghe said the attacks were the result of an intelligence failure. “India had shared information on a possible attack, but there were lapses on the part of authorities here,” he said.

President Maithripala Sirisena has called for a united effort to fight terror. “Action will be taken against the officers who failed to act. Changes will be made in the top rungs of the security forces,” he said.

The “burning question”, according to Sirisena, is why the police failed to act. “I want to state here that I wasn’t informed either. Had I been informed, I would have acted immediately,” he said.

The parliament’s first meeting after the attack, on April 23, saw the ruling party and the opposition trading charges. Opposition leader Mahinda Rajapaksa said such attacks would never have happened if he were in power. “We had strengthened the intelligence services so that there would be absolutely no threat to national security,” he said. “Whenever we got wind of a threat to national security, we acted on it.”

Apparently, there were several tip-offs. “Intelligence agencies abroad had warned the government on April 4 about the possibility of attacks,” said Health Minister Rajitha Senaratne.

Hours after the blasts, a note apparently sent by a top police officer, dated April 11, began circulating on social media. Addressed to the security divisions of various ministries, the diplomatic community, judges and former presidents, the note warned of impending suicide attacks on churches and the Indian High Commission. According to it, the plot was masterminded by “Mohammed Zaharan, leader of National Thowheed Jamaath”, a radical Islamist group that was earlier accused of vandalising Buddhist statues.

The authorities apparently dismissed the note as a “fake document”. After Senaratne named National Thowheed Jamaath (NTJ) as the group behind the blasts, it became a talking point.

The motive for the attacks remains unclear. According to the government, the blasts were in retaliation for the Christchurch shootings in New Zealand in March. The police have arrested around 50 suspects from across the country. “There were nine suicide cadres—all Sri Lankan nationals—involved in the attack,” police spokesperson Ruwan Gunasekara told THE WEEK. “The criminal investigation department has identified eight of them. Persons arrested are all Sri Lankan citizens. Of the suspects, 32 are in custody and are being interrogated.”

The investigators tracked the attackers to Dematagoda, near Colombo. Apparently, all were educated and belonged to well-off families. “One went to the UK to study. One suicide bomber was a woman,” said Gunasekara.

Defence Minister Ruwan Wijewardane said all attackers had been to Syria. But it is not clear whether they were trained there. Investigators say the attackers had links with NTJ and another little-known group called the Jammiyathul Millathu Ibrahim. “We are investigating the involvement of JMI and NTJ,” Gunasekara told THE WEEK.

The authorities are yet to establish NTJ’s links to Islamic State, which has claimed responsibility for the attacks. IS has released photos and videos of what it claims are jihadists who were trained to carry out the blasts. If the claim is true, IS has carried out its deadliest attack outside Iraq and Syria.

The police are investigating whether IS cells are active in Kattankudy, a Muslim-dominated town in eastern Sri Lanka. Muslims, mainly Sunnis, have significant presence in eastern Sri Lanka. After the spate of attacks against them in March last year, international security agencies had warned the Sri Lankan government of the threat of radicalisation of Muslim youth.

In January, security agencies had detained four people after unearthing a huge cache of explosives from an 80-acre coconut farm in Puttalam district in northwestern Sri Lanka. All four, including the owner of the farm, were released later. The police are now investigating whether the case is connected to the blasts.

“Intelligence agencies believe that the attacks are the handiwork of an international jihadist organisation,” said an officer. “The reason is the sheer sophistication of the attacks—six sites in three cities hit by nine suicide bombers. Nearly all of the explosives went off with deadly effect.”

Investigators say it points to the involvement of an expert bomb-maker. Also, the plot itself could have taken more than a month to hatch. “A plot of this magnitude means that it was no small cell,” said the officer. “Imagine the backup you need. Who drove the attackers to the sites? What safe houses did they use?”

The questions are burning, and so is the situation in the country. “The army has taken over,” Wijewardene told THE WEEK. “The situation is under control now. Interpol and intelligence agencies from India, the UK, Australia and the UAE have offered help.”