In his meticulously researched and sharply argued book Indira Gandhi and the Years that Transformed India, historian Srinath Raghavan offers a clear-eyed account of a tumultuous era in Indian democracy. Spanning the period from her rise to power in January 1966 to her assassination in October 1984, the book is the result of over 15 years of research, enriched by access to newly declassified files. The Indira period, he argues, left a lasting impact on the politics and economy of the country.

Raghavan writes with a scholarly and restrained tone, letting facts speak. He avoids the temptation to draw parallels, preferring to let readers see for themselves how the past may echo in today’s politics. He states that Indian politics shifted fundamentally after 1967, when the Congress party’s dominance began to weaken and executive power became concentrated in the prime minister’s hands.

Raghavan describes how Indira Gandhi introduced what he calls a “Caesarist” style of leadership. In this model, popular support matters more than institutions. The leader connects directly with the people, bypassing party structures and parliamentary checks. Elections become more about personal approval than party platforms. Indira’s 1971 campaign is the key example: faced with opposition within her party, she launched the slogan Garibi Hatao and went on a whirlwind tour—36,000 miles in 43 days, and 300 rallies, speaking to around 20 million people. The result: 352 seats for the Congress. The second largest party, the CPI(M), could win only 25.

The author keeps circling back to the Caesarist model as he dissects the defining events of the 1970s and 1980s. “Indira Gandhi came to the view that with rising electoral participation and expectations, the older patterns of political mobilisation and representation had come unstuck. The plasticity of the social world enabled new modes of popular politics, electoral Caesarism being hers,” he writes.

He again writes of 1973-74, when the railway strike was underway, the prime minister proved her Caesarist credentials by testing a nuclear device to rapturous applause.

But this Caesarism had its limitations—it could not be passed to others as the country witnessed a long era of coalitions, until recently. There is no turning back to the parliamentary era of Nehruvian democracy.

Indira’s leadership, Raghavan argues, brought three major changes: stronger executive power, politics built around personality rather than process, and an economic focus on state-led poverty relief, whose echoes are found in today’s India. Garibi Hatao now comes in the form of welfare schemes for the poor.

These laid the ground for Emergency in 1975. Days ahead of the declaration, the Congress parliamentary party had adopted a resolution with an overwhelming majority that Indira was “indispensable to the nation”.

Raghavan’s style is very understated, like in the description of key personalities. He describes lawyer and former minister of education S.S. Ray, for example, as someone “who brought to table a modicum of legal knowledge and a political sensibility unsalted by constitutional propriety”.

The same tone brings the readers to spot the continuity. Indira went on radio to announce bank nationalisation in 1969 in the name of financial inclusion, particularly for the marginalised. Sounds familiar? (Even demonetisation was announced by PM Narendra Modi on television at 8pm on November 8, 2016.)

The book is more than just a political biography; it charts the entire arc of politics then. It is thorough and makes for an enjoyable and thought-provoking read. Coming at a time when her contributions and decisions are being recalled by either side of the political divide, the book fills the critical gaps which other works on her could not. It is an essential read for anyone seeking to understand the making and the remaking of modern Indian democracy.

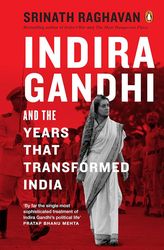

INDIRA GANDHI AND THE YEARS THAT TRANSFORMED INDIA

By Srinath Raghavan

Published by Penguin Random House India

Price Rs899; pages 367