On June 18, when C. Vijaya Kumar called his mother Kaathammal from New York to share his happiness on winning an award, she replied “oh! Appidiya?” (Oh! Is it?), without much enthusiasm. But the next day when a flex banner of him was put up in the heart of her hometown—Samudirapatti in Tamil Nadu’s Dindigul district—Kaathammal understood that her son had done something big, and she asked around to find out what it was. People told her he had won an Oscar. “We congratulate C. Vijaya Kumar, the son of Chinnazhagu Ambalam and Kaathammal for winning the James Beard (Oscar like) award for the first time from India and for bringing fame to our Samudirapatti village,” read the banner. The next day, Kumar called his mother again and this time, she was brimming with excitement.

“My parents thought I will become an engineer or doctor,” says Kumar over Zoom from his restaurant Semma, the only Michelin-starred Indian restaurant in New York City. “My mother thought being a chef was just another job to make money. But now she has understood that this is more than being a doctor or an engineer.”

Set in Greenwich in the heart of Manhattan, Semma offers American diners a contemporary take on south Indian cuisine. It is run by the hospitality group Unapologetic Foods, under Roni Mazumdar and Chintan Pandya. Semma in Tamil translates to ‘awesome’, and the dishes—from nathai pirattal (spicy snail dish) to kudal varuval (goat intestine fry) and gun powder dosa—live up to the name. With Kumar at the helm, the restaurant was launched in 2021, shortly after the Covid lockdown. Breaking away from the standard Indian fare in America—spicy butter chicken and roti—was risky, but even more so was a daring decision the Semma team took: to promote the chef and his story. It showcased his early culinary experiences and the summer vacations he spent with his grandmother at Arukkampatti, a hamlet near Dindigul. “It was quite risky and challenging,” he says. “I was very scared as it could go either way. But thank god we got some coverage in the local media and diners began pouring in.” A year after its launch, Semma got a Michelin star, a rare fine dining recognition for down-to-earth, rural Tamil Nadu cuisine.

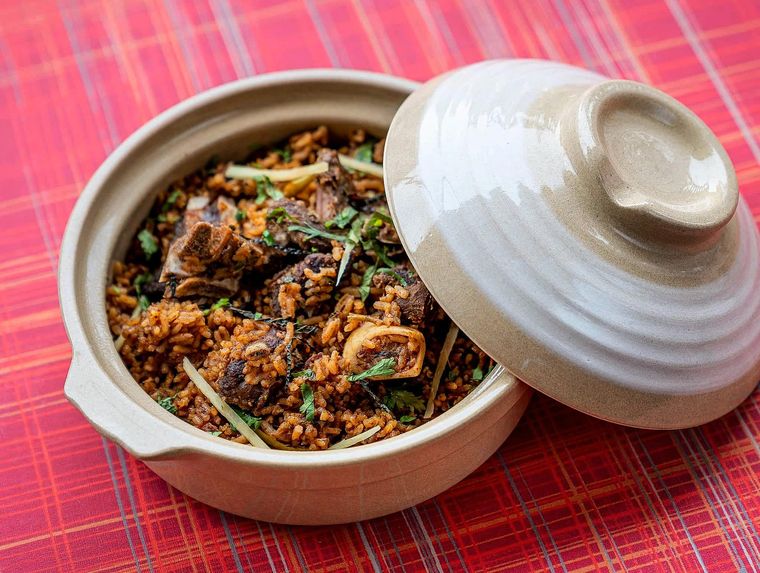

As a young boy from a farming family, Kumar was always in awe of his grandmother’s recipes whenever he visited Arukkampatti. He and his friends used to go hunting for snails, and swimming and fishing in the nearby lakes. There was no electricity in his grandparents’ home, so that meant no television. There weren’t even any buses to reach the village. Upon their return, they would hand over the snails to their grandmother, who would clean them, add ginger and tamarind with spices and cook in a clay pot over wood fire, to be served on fresh banana leaves. When he came back home to Samudirapatti, he remembers his father going deer hunting, which wasn’t illegal then. His mother would cook it with ground spices and serve hot. Now, 20 years later, his cuisine is a tribute to the delicious recipes of his childhood. Kumar takes pride in his heritage, and in taking his grandmother’s flavours from Arukkampatti to America.

Not that becoming a chef was an easy decision. Being good in studies, everyone was surprised when he chose to enrol at a culinary college near Trichy. He was mocked a lot for his decision, with friends and neighbours asking why he needed to go to college to learn cooking. Today, his parents’ disappointment has turned to pride, when his journey took him from Taj Connemara in Chennai to Dosa in San Francisco. The first Michelin restaurant he worked in was Rasa in California, before he teamed up with Mazumdar and Pandya of Unapologetic Foods, who run popular restaurants like Dhamaka and Adda in the US. “Most of the diners in New York prepare less spicy dishes to match the taste of the people here,” says Kumar. “Because of this the originality of the dishes is usually lost. We never wanted to fit into anyone’s mould. We decided to present authentic flavours unapologetically.”

But ask him how he got the idea and he narrates an interesting story. At his grandmother’s house, the snail delicacy, or nathai pirattal, was his favourite. But back in his mother’s place, he would never think of having it or taking it to school, as everyone there would ridicule him. But when he went to culinary school, he learnt that snails or ‘escargot’ was a French delicacy. “I was pleasantly surprised,” he says. “I remember thinking how a ‘poor man’s food’ became a delicacy in France.” It was then that he decided to try and turn the regional into the elite. And now, his dishes like millet khichdi, Dindigul biryani, Chettinad maankari (venison or deer meat) and mulaikattiya thaaniyam (sprouted moong dal), testify to a triumphant story of rural resilience re-imagined as fine dining on the world stage..