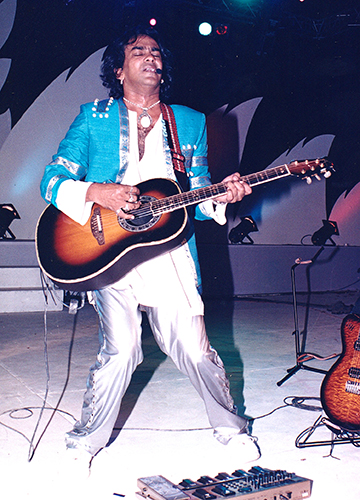

For Indians who listened to the Bee Gees, The Beatles and Bono in the 1980s, the indie music movement in their own backyard was a revelation. On the radio, they began to hear their own countrymen not merely mimicking American pop-rock, but owning it with a desi touch. And nobody owned it like Remo Fernandes.

Fans of Hindi music would later know Remo to be the voice behind hits like ‘Jalwa’, ‘Humma Humma’ and ‘Pyar To Hona Hi Tha’, but he refused to be defined by his Bollywood numbers. Instead, India’s “original rockstar” popularised fusion on these shores. “If I saw the guitar as male, the flute was the female that completed it,” he writes in his recent autobiography, Remo.

The fusion of cultures and genres that this Goan native introduced was scoffed at by ustads, “but perhaps all turned to it sooner or later”, he tells THE WEEK.

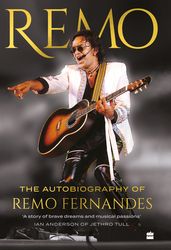

The autobiography was a project that was as close to his heart as his music. So much so he considers it a work of art in itself. Locked down during the pandemic in his hometown of Siolim, Goa—far from Porto, Portugal, the place he now calls home—Remo finally got down to completing the memoir he began writing 11 years ago.

“Writing one’s story… helps you put your life into perspective like not much else can. How would you understand where I’m at today if I didn’t tell you where I’m coming from?” says the 68-year-old.

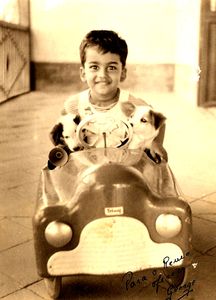

Indeed, where he comes from is a large part of Remo’s identity and music. He goes into great detail to describe his roots and his childhood in easy, breezy Goa. His words hark back to a simple time in a beautiful state.

And it is with purpose, too. To remind young Goans of what they are missing. “Both [young and old] are surprised at my memory for detail. That’s a great advantage to being my age; to have known a Goa no one will ever know again,” he says.

Besides serving as an ode to a bygone Goa, Remo reminds us that musicians today have much to learn from this legend. Growing up in a time and place when youth were increasingly experimental, he writes about shouldering a moral responsibility to warn youth against “drugs, communalism, corruption” and “careless immature sex” through his music.

“When I was a teenager, my heroes from The Beatles to Eric Clapton were glorifying drugs, and that encouraged a lot of global youth to turn into addicts—and even die,” he says. “I, too, was inspired to get into the milder marijuana and hashish. But a lot of good lyrics were being spread through rock’n’roll too, notably anti-war, anti-racism and pro-ecology. And I decided to use music to spread positive messages, and to make being anti-heroin (among other things) cool for the youth who attended my concerts.”

Over the 480-odd pages of his memoir, the musician takes us through the highs and lows, ecstasies and tragedies in his storied life. And there is no dearth of anecdotes either—be it about delivering his albums on a yellow scooter, tripping on Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club, forgetting that he sang for ‘Humma Humma’ when the song was released, not knowing which chord was ‘E’ when asked, and venturing into fusion in 1975. Fusion, because he wanted to make music that would “make the body move”.

Not to forget, it is an offering laced with humour: “If only, together with the yoga exercises stolen from India, Jane Fonda had introduced our toilet hygiene habits to the West, they needn’t have had all those squabbles and fights over paper rolls as long as they had plain water, soap and a (preferably) left hand,” he writes about people hoarding toilet paper at the start of the pandemic.

He notes that he felt like a rock star for the first time when girls rushed on to the stage after his performances at the ‘Festival of India’ in the USSR in the late 1980s. Rajiv Gandhi wanted to project a “young, vibrant image” of India and Remo was among those chosen for the mission. Rajiv and Remo shared a mutual admiration for each other and the latter reveals he was deeply disturbed by the prime minister’s assassination.

Something that has perennially needled Remo is the lack of originality in the Indian music scene. He told THE WEEK in a 2004 interview that Indian rock bands simply copied the west. But he resisted it. In Remo, he recounts the time when Pepsi approached him to make a Hindi version of a Michael Jackson song for a jingle. They were unsure if Indians could make good rock and pop. Remo says he refused and instead made ‘Yehi hai right choice, baby’ which was instantly approved.

One would assume that a musician from that time would be fighting to stay relevant. But that is not Remo’s style. He is taking life as it comes and enjoying the work he still produces. He recently completed writing his modern opera, Mother Teresa and the Slum Bum, inspired by his meeting with the Mother in the 1990s.

As life slowed down for artists over the last two years, it helped him, too, as he delved into the creative depths of his mind and wrote this incredibly vivid memoir besides new songs.

“Creative artists have certainly used this ‘me’ time to create, away from the lure and demands of the commercial world. Those who merely copy and replicate bemoan their boredom and lack of income,” he says.

The book is a journey. One to be read on those warm Sunday afternoons, just like you did listening to his songs on the radio.

Remo

By Remo Fernandes

Published by HarperCollins

Price Rs799; pages 508