There is a tense stillness in Tom Vattakuzhy’s works exhibited at Lokame Tharavadu (The world is one family), a larger-than-life art show taking place in the port city of Alappuzha in Kerala. In one, a blazing sky hovers over a house, threatening to engulf it any moment. Even in the stillness, one can sense the suppressed motion. As though the clouds are on their way from the canvas to some unknown destination. Somewhere nearby a storm is brewing. The colours used are stark—an angry grey bruising the skyline. The house might be a metaphor for the artist’s mind, a bulwark against life’s chaos.

For Bose Krishnamachari, who conceptualised the show, ‘home’ represents the universal spirit of humanity. “A Malayali’s nature is like that of a chameleon,” he says. “They merge with the surroundings wherever they go. That is why I called the exhibition, ‘The world is one family’. I wanted to capture this spirit of acceptance.”

From Kasaragod to Thiruvananthapuram, from tea shops in small rural pockets to urban drawing rooms, Krishnamachari went searching for his artists. Kerala, he says, is the most receptive place for ideas and ideologies. Malayalis are raised on Kafka and other philosophers, and this is reflected in the surrealism of their works.

Krishnamachari has provided the perfect space for these works—musty warehouses and dilapidated factories transformed into gallery spaces with architecturally smooth lines and a maze-like flow to them, like grooves in which thought is trapped. The show is spread out across seven venues in a 2sqkm area. They have already sold works worth Rs3 crore, says Krishnamachari.

Interestingly, for a show that is hinged on the theme of oneness, it is the diversity that comes through. Whether it is in the themes (gender, identity, memory, society, patriarchy, inequality and migration) or the mediums (digital works, photography, videos, assemblages, paintings, augmented reality and graphics). Perhaps what binds is the inward gaze, a meditative search for emancipation from a world of ‘isms’.

Take the work of C. Bhagyanath, an artist based in Kochi. As a migrant from a rural to an urban space, his cityscape is a sphere of restless activity, with people striving to climb to higher platforms. Yet, each platform seems brittle, breakable. Any moment it might all give way—the edifice of dreams, hopes and ambitions—into a collective heap at the bottom. Against the inky blackness, the people are pinpricks of light. But, being birthed from the dark, can we really be creatures of light?

While some artists like Bara Bhaskaran personalise the political—his ‘Chambers of Amazing Museum’ imagines the lives of the women who were widowed during the Punnapra-Vayalar revolt of 1946—others politicise the personal. Like artist Indu Antony, who has collected discarded photos of women found on the road and in antique shops. These women, says Antony, have become a part of herself. But these photographs are ephemeral, much like the abandoned women. Before they fade into nothingness, she stitches their edges with her hair. The only part of the photographs that will remain, the hair will frame the empty spaces where once inhabited people with everyday concerns, habits, expressions, personalities…. “Weaved with my hair, this poem is a reflection of a journey and a time,” she writes.

The exhibition showcases both the works of established artists like K.S. Radhakrishnan, Jalaja P.S. and Jitish Kallat as well as those who are relatively newcomers. “I chose artists based on their creativity and consistency,” says Krishnamachari. “Whether they were poor or well-off, or whether they had won awards or not, did not matter to me.”

Much like the people of Kerala, one can witness an amazing diversity in the exhibits. There are political, ideological and nostalgic works, and those suffused with the wonderful whimsy of magic realism. Some are a social commentary, like the works of Blodsow V.S. In one, he captures the travails of saleswomen in textile shops by showcasing a spectrum of vivid blouse materials. The work also highlights the struggle of lower caste women in erstwhile Kerala for the right to wear a blouse. The fabrics provide a portal to connect the past with the present, while at the same time making a statement about body, control, labour and gender constructs.

“While I was working at the Cholamandal Artists’ Village in Chennai, I came to Kerala one Onam to visit my girlfriend,” says Blodsow. “I happened to visit a textile shop with my girlfriend and mother. When I saw the materials for the blouse pieces, immediately the idea struck. During my research on the spectrum series, I came across the work of Ellsworth Kelly and this series is a tribute to her.”

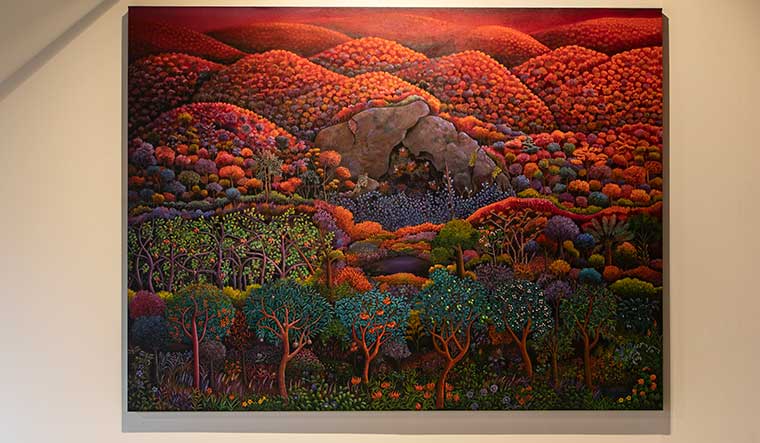

For Smitha G.S., the desolation of the pandemic led to a brilliant series of paintings in which she conceptualises the world as she wishes it could be. The reddish-gold hills fade into an impenetrable future and the rocks are relics from her childhood. “During Nipah, I used a colour palette of grey,” she says. “I don’t know why. The colours are a representation of my mood. I don’t choose them. They choose me.”

As you make your way outside, the blinding sun silhouettes clusters of people—laughing students grouped on the sidewalk, looking like they walked straight out of a college catalogue; men smoking beedis in shaded spots; passers-by who seem to know exactly what they want and are headed towards it. One walks out into the bustle of life, as though released from the floodlit corners of these artists’ imagination.