Even though William Dalrymple's City of Djinns: A Year in Delhi (1993) is a travel memoir, for some of us it is also a lesson in history. For historian Dalrymple, the shift to travel writing came in the 1990s when he discovered the ill-fated love story between James Achilles Kirkpatrick, East India Company resident at the Court of Hyderabad, and Khair un-Nissa, a Persian noblewoman. And thus was born White Mughals (2002), which brought alive a lesser-known world when the east and west easily consorted in the age of the Empire.

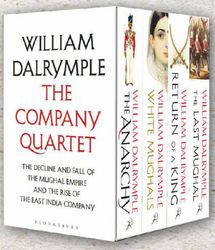

Ever since White Mughals, Dalrymple has continually invited the general reader to enter his stylistic, intriguing world of history, where oft-heard stories are retold in a distinctive voice by tapping into primary sources previously unread. White Mughals, The Last Mughal (2006), Return of a King (2012) and The Anarchy (2019) bookend 20 years of his writing on the breathless rise and fall of the East India Company. Bundling these four books into a box-set called The Company Quartet was bound to happen. In a way, the set is dedicated to the memory of Bruce Wannel, Dalrymple's long-time collaborator and translator, who died last year. He had helped unlock rare Persian texts, obscure manuscripts and calligraphies unearthed by the historian.

In conversation with THE WEEK, Dalrymple tells why it is time for him to turn over a new leaf:

Is The Company Quartet the last recounting of India under the Company from your end?

For the time being, yes. It ends my 20 years' work on the subject. I didn't write these four books in chronological order. But together, they tell the whole history of the East India Company. The Anarchy is chronologically the opening of the story as it begins in 1599 with the founding of the Company. And The Last Mughal deals with the closure of the Company with its nationalisation in 1858. Before I left Delhi in May, I filed a lot of my Company stuff into boxes and put it up in the attic. Now, I am looking at a very different world of classical India—between 200BCE and 1000CE, when India was beaming its civilisation out over Asia. It is something I have explored in articles and magazines, but not between hardcovers. I have never actually written a chronological history of this period. And I am loving it.

This is also about narrative history and the art of writing narrative history. Tell us about your disenchantment with academic history writing when you were studying at Cambridge, considering that you immediately moved to travel writing thereafter.

It wasn't that I was disenchanted with academic history writing. But I very much enjoyed university and discovered there and read extensively the work of a Cambridge historian called Steven Runciman. He was the great historian of the Crusades and Byzantium. As a medievalist at Cambridge, I read his work and loved it. What was amazing about him was he used extraordinary primary sources and a huge variety of languages. But he wrote up his results as narrative, with characters as carefully sketched as portraits of any novelist, with physical descriptions of people, with biography and human emotions playing into the story from the primary sources. He wrote about it in beautiful prose. The decision of what language to write a book in, whether to write it in academese or in a literary language, has no bearing on its veracity and reliability of historical thought. But what I think is odd is that so few Indian historians have written for a general audience in a literary fashion. In a non-academic language. When I started writing here, there was nothing in India being written in history which a normal intelligent reader would want to read; the same sort of person who might enjoy Salman Rushdie. That is changing now. A lot of younger historians like Ira Mukhoty and Manu Pillai are writing very scholarly works which are highly regarded and win prizes. They are written in clear, non-academic prose and they are very popular. What I am doing now is not odd or unusual, it is quite mainstream. But that was not so, 20 years ago.

Was the discovery of the story of James Kirkpatrick the turning point in your writing career?

There were several things that happened. Yes, discovering the Kirkpatrick letters that had just been catalogued and made available in the British Library was one of them. And then finding the Persian half of the story in Kitab Tuhfat-ul-Alam was another. But also, there was something happening in my personal life. I had been a foreign correspondent running around war zones. And just the year before I began [working on the White Mughals] my daughter was born. Suddenly I had an infant in the house and the urge to go off into war zones hugely diminished. I had a duty to be at home. I began White Mughals in 1997 and the book finally appeared in 2002. A five-year epic time; it nearly bankrupted me.

There's heated anxiety around the Central Vista project in Delhi. Having engaged with the historiography of the capital, what does this symbolise for you? Is it like the reconquest of Delhi in history books, all the razing and rebuilding?

Well, there is a great aphorism that those who build New Delhi lose it. Prithviraj Chauhan built New Delhi and he lost it. So did Firozshah Tughlaq and Shah Jahan. Even the Britishers lost after they built Lutyens' Delhi.

A poll in March 2020 revealed that a third of Britons believed that the Empire did more good than harm for its colonies. What explains this opinion in 2021?

I don't think people in India quite realise that the Empire is absent from British history curriculum. You can go all the way through the British schooling system and do an A-level in history and never read about the Empire. This is something that has to change, because there is national amnesia. The British are surprised when they come to India and find that their ancestors are regarded as looters and plunderers. You would not believe the degree of ignorance, even among educated people, government ministers and diplomats about this. That is one of the reasons I have written these books.

The Company very clearly was a corporation that was trying to make a profit, no argument about that. It had no ulterior motives of a civilising mission. So, it seems to me that the East India Company is the forgotten bit of the British story.

If you have to choose a historical character from The Anarchy and expand it into a book as a separate story, who would that be?

I think it would be about Tipu Sultan. There is obviously a book there and it would be a very controversial one. Because Tipu—while he is now typically reviled by the right and regarded as a jihadi and a tyrant—was an extraordinary character who gave more grief to the British than any other ruler in this country. He never allied with them. The Marathas fought the British several times, but they also allied with them.

The Company Quartet

By William Dalrymple

Published by

Bloomsbury

Price Rs2,790