Ask Marina Wheeler what her most vivid childhood memories are, and she will recount a supper where she, her sister and her parents took turns to say what they were good at. When it was the turn of her mother, Dip, her father, Charles, prompted her with: “You are good at cleaning the lavatory.” A frustrated stay-at-home wife, Dip did not appreciate the joke. Instead she insisted he take it back or she would pour ketchup on him. He went on laughing so she kept her word. “It really was something seeing his shock and all this red goop on his white hair,” Wheeler says.

Her father Charles, one of Britain’s most distinguished foreign correspondents, was then based in Brussels as the BBC’s Europe correspondent. Now, decades later, after the death of both her parents, Marina has written a book about her mother called The Lost Homestead: My Mother, Partition and the Punjab. “I wanted to bring her out of my famous father’s shadow,” she says.

It is hard not to see the parallels. At 56, Wheeler might have spent years as a renowned barrister as well as bringing up four children, but she is better known as the long-suffering wife of Bonkin’ Boris, whose rise to becoming the British prime minister was accompanied by a string of extramarital affairs, all splashed across the tabloids. Wheeler may never have poured ketchup on that famous blond mop, but she often changed the locks on their Islington home in London and kicked him out.

Now, after two turbulent years that have seen the end of her marriage, her battle with cancer, the death of her beloved mother and her ex moving into 10 Downing Street and acquiring a much younger fiancée, a rescue dog and another baby, Wheeler has, she says, finally moved on.

Indeed, the door of her new terraced house in a trendy, cobbled part of east London opens to reveal a woman with a wide pixieish smile, fashionably dressed in a taupe silk shirt, swishy black pants with broderie hems and lace-up boots. She looks every inch the glamorous divorcée.

She shows me through to a vast, brightly-lit room lined with bookshelves. On the coffee table is a cafetière and a tray of pastries. She bought the house after her divorce came through in February and moved into it in June. “I feel excited,” she says. “This, for lots of reasons, is quite a pivotal moment in my life. My long marriage ended, my last two kids off at university, my parents no longer around, the shifting around of places.... I feel I am free to pick how I spend my time in a way I have not been for decades.”

She is also celebrating the publication of her book. It is set during the Partition in India in 1947. The story is told through the eyes of her mother’s family. Because of her name, light olive skin and dark hair, people often assume Wheeler is Greek, but her mother, Dip Singh, was Indian.

Her book had a difficult birth. Last year, her plans for going on a writing trip with a friend were upended when a routine smear test revealed abnormalities. When a doctor at London’s Whittington Hospital told her she had cervical cancer, her reaction was, “I have no time for this. Quite apart from anything else, I have a book to write.”

The diagnosis and three subsequent operations put paid to a writing trip to Russia. A reaction to the gas used in keyhole surgery made her appear like a “balloon... I looked like I was recovering from an amateur facelift”. After she had recovered, her mother died of bowel cancer in February. Then the pandemic hit, and in April, Johnson was diagnosed with Covid-19 and placed in intensive care.

Wheeler’s mother was born in the Punjabi town of Sargodha, the fifth and youngest child of a Sikh doctor who ran a clinic for the poor. He was also president of the municipal committee that helped the British rule the town. A prosperous man, he owned farmland and an ice factory. They lived in an opulent house with Italian marble floors, many bedrooms and rose gardens, which Dip described as “idyllic”.

When Dip was 14, however, the family was forced to flee during Partition, when their part of Punjab ended up in the newly created Pakistan. They left behind their comfortable life—and the bike she had just been given for her birthday—and moved to Delhi.

The project came about after she mentioned her family history in a review she wrote of the film Viceroy’s House in 2017 and an editor contacted her suggesting she write a book on it. The result is a charming memoir that weaves the story of Indian Independence and the tragedy of Partition with that of her mother’s escape from an unhappy marriage and daring quest for personal freedom. Eventually she married Charles, whom she met while he was posted in Delhi.

I mention the parallels between her mother living in her father’s shadow and her own marriage. She immediately stiffens. “That is my least favourite subject,” she says. It is not hard to understand why. Johnson had a long-standing affair with Petronella Wyatt, his deputy at The Spectator. Then came the art dealer Helen Macintyre, with whom he has a child, and Jennifer Arcuri, the Californian tech entrepreneur who gave him “IT training” in her Shoreditch flat in London. And now, of course, he is engaged to Carrie Symonds, who at 32, is only five years older than Johnson’s eldest daughter.

Johnson and Wheeler finally separated in the summer of 2018, just before he resigned as foreign secretary over Theresa May’s Brexit deal. Infidelity, apparently, had been a recurring theme in Johnson’s parents’ marriage, too. A new book by Tom Bower claims Johnson’s father, Stanley, had a string of affairs.

Wheeler’s childhood, however, was far more stable. When she was a toddler, they moved to Washington, where her father was posted, a time she describes as “idyllic”. It was a fascinating time. Charles made his name covering the race riots, the assassinations of Martin Luther King and Robert Kennedy, the protests against the Vietnam war, and Watergate. After Washington, the BBC sent her father to Brussels, and the girls went to the European School there. This is where she first met Boris, who was her same age and studying there while his father was head of the European Commission’s newly established Prevention of Pollution division. Back in the UK, the family moved to Garden Cottage, a country home in West Sussex that her parents had bought years ago. The two girls were sent to the independent school Bedales, in Hampshire.

She read law at Fitzwilliam College, Cambridge, did a master’s in EU law in Brussels and began working there as a barrister. There, she again crossed paths with Johnson, by then The Daily Telegraph’s Brussels correspondent. He was in the process of breaking up with Allegra Mostyn-Owen, his first wife and fellow Oxford graduate. Wheeler was already eight months pregnant when the couple married in 1993. In his usual chaotic fashion, Johnson managed to get his divorce papers signed just in time. Lara Lettice, now 27 and a fashion journalist, was the first of their four children. Then came Milo Arthur, 25, Cassia Peaches, 23, and Theodore Apollo, 21.

It cannot have been easy juggling work and raising four children? “If you talk to my kids they will each regale you with horror stories of things I failed to do,” she admits, laughing. “I forgot Cassie’s induction day, so she arrived at school when everyone else had already made friends. And I remember taking Milo to watch his Christmas play, thinking, ‘great, I am so efficient’, but it turned out he was actually meant to be in the play.”

Johnson began his affair with Wyatt around this time. When the news came out, he denied it as “an inverted pyramid of piffle” until Wyatt’s mother, Verushka, lost patience and went public. It was the first time Wheeler changed the locks and took off her wedding ring. When I ask her about this, she stiffens. She is more interested in talking about her mum, she says.

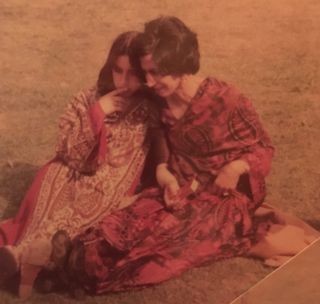

Her mother, who got a degree in Russian and then, years later, an Open University degree in experimental psychology, sounds like a remarkable woman. She worked for years at Amnesty International as a researcher, catching the 7am train to London each morning. Though she wore saris and cooked Indian food, Dip never talked about her life in India. Thus began a quest involving six trips to India and two to Pakistan, as well as many visits to her aging mum, who lived alone in Sussex following Charles’s death, to try to get her to open up. She shows me a childhood photo of her and her sister on the SS France with her parents, and her grade two cello certificate that she found recently while sorting through her parents’ papers at the house in Sussex.

Once she is finished with that, she has many more projects planned. Now fully recovered from cancer, she wants to become involved with the Eve Appeal—UK’s gynecological cancer research charity—and raise awareness about the need for regular smear tests, particularly during the pandemic. She also wants to work with refugee women and perhaps write another book—though not on life with Johnson. “I think my marriage is the least interesting thing about me,” she says. Like her mother, poised with that ketchup bottle, she refuses to be defined by a man.

THE LOST HOMESTEAD: MY MOTHER, PARTITION AND THE PUNJAB

By Marina Wheeler

Published by Hodder & Stoughton (Hachette India)

Price Rs699; pages 336