The drama began in September, when Tavleen Singh, the mother of British-born writer Aatish Taseer, sent him a WhatsApp message—a letter sent by the home ministry of India, informing him that the government was revoking his Overseas Citizenship of India. An OCI status is the closest thing to a dual citizenship in the country and allows one to live and work here. Aatish got the letter on the 20th day of the 21 days the government had given him to respond. Although he immediately responded, on November 7, the government announced via Twitter that his OCI status had been cancelled. The reason given was that he had concealed “the fact that his late father was of Pakistani origin”.

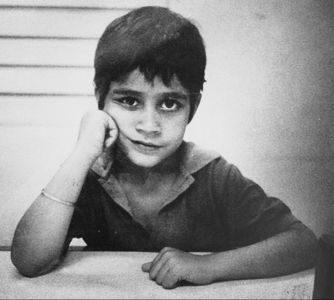

Contrary to the government’s claim, he has never tried to hide it. In fact, he has written extensively about it in his first book, Stranger to History: A Son’s Journey Through Islamic Lands (2009). Aatish, 39, was born out of wedlock to a Muslim father and a Sikh mother; Salman Taseer was the governor of Punjab in Pakistan when he was assassinated in 2011. Aatish is a British citizen, but since the age of two, he has lived in India with his mother and grandparents. Although he studied at Amherst College in the US and now spends a large part of his time in New York with his lawyer-husband Ryan Davis, India remains home.

Taseer who, in many ways, has the soul of a poet and whose own prose is often imbued with a lilting cadence, can also be scathing in his writing. Especially when he directs his full intellectual firepower at, what he calls, the “cauldron of religious nationalism, anti-Muslim sentiment and deep-seated caste bigotry” that India has become. Many of his articles have been deeply polarising. But perhaps his most divisive one has been India’s Divider in Chief, that appeared in TIME magazine in May, and was highly critical of the Narendra Modi government. The piece was, he says, one of the primary reasons why the government revoked his OCI status.

In a way, his last book, Twice-Born: Life and Death on the Ganges, was a goodbye of sorts to India. “I don’t think I can live here,” he had told THE WEEK a little over a year ago. “I think India is going to be a place where a certain kind of English-speaking person of my background will have a harder and harder time. But to be gay, to be Muslim, I am at too sharp an angle to it.” It is ironic that the country to which he had decided to bid farewell is the one to which he is desperately fighting to return. But it is a war, he says, he has no option but to wage. “Everything is at stake—family, country, my material as a writer,” he told THE WEEK in an interview. “I will fight on. On the beaches and in the shakhas, in court rooms and newsrooms. And one day, they will be gone. And I will still be here….”

Q/ If you were to write India’s Divider in Chief today, would you be more careful about what you wrote?

A/ There is no question of being ‘more careful’, as you say, or self-censoring. It is those who restrict freedom who need to be careful. There is an undertow of dissent and dissatisfaction in India. I could feel it when I was there, a few months ago. I was travelling widely and there was something sullen and angry in the air. Even in the bluster of the Modi supporters, I detected a note of desperation and disappointment. The response of the government is to conceal their failure in effusions of pride, to fix the perception rather than the reality. It is the response of the provincial. People know the difference between the warm self-assured glow of patriotism and the ragged hysteria of nationalism. I suspect Messrs. Modi and Shah have an earthquake coming their way—an anger that is yet to find utterance, and that will feel almost like an anger at oneself at having submitted to the hypnotic tune of the snake charmer.

Q/ How has the trolling and the constant hounding affected you? Could you describe the last few days, ever since the controversy broke?

A/ To tell the truth, once the government’s perfidiousness was exposed, I have been feeling rather good. The uncertainty of the months between the government’s letter and the cancellation was bad. We were being advised to make gestures of conciliation and to cosy up to gruesome mediocrities. Now that they have presented us with a fait accompli, I fully intend to fight them. Look where they have ended up just in the court of public opinion. They have been working overtime to cultivate the image of Modi as the great statesman abroad and in two swift weeks, virtually every newspaper in the world is describing him as the harbinger of a new dark age.

Q/ Most Indians take their national and ethnic identities for granted. As the son of an Indian journalist and a Pakistani politician, who has lived and worked both in India and in the west, you must have experienced some sense of unbelonging. What does it feel like to live with a fractured identity?

A/ I used to think of hybridity as a privilege, with all its possibility of being part of different worlds. I see now that it is also a liability. In Stranger to History, I had written: “These mismatches were the lot of people with garbled histories, but I preferred them to violent purities. The world is richer in its hybrids.” Hybridity is true not just of me, but of an ever larger group of people, both in India and abroad. This is not just the result of globalisation. Identity on the subcontinent, with its special interplay of caste, class, religion and language, is—and has historically always been—an extremely complex thing. The world has never been unmixed. What is new and produces, as you say, a sense of “unbelonging”, is the desire to simplify complexity, to homogenise identity, to iron out difference. Deep down, though, I feel that hindutva’s wish to impose a tyranny of sameness on the variety of Indian life—one language, one religion, etc—will not work. India has always solved the problem of “the one and the many” in its own way, without doing violence to complexity. It has let society find a natural equilibrium, through absorption and assimilation. That astonishing syncretism is part of the Indian genius.

Q/ You have described having an idyllic childhood in Delhi, a place that was a cultural melting pot those days. Could you describe the underlying pain of not being allowed entry to a country you call home, and in which you grew up?

A/ It was my grandmother who first brought me to India as a baby. I lived with my grandparents until I was nine. The love they showered me with gave me my sense of belonging; it insulated me from the world. My pain at not being able to return home is intimately connected with a feeling that the capaciousness of old India—that gentle, glamorous country—has been betrayed by a mean-spiritedness that feels unIndian. My parents’ love affair would have scandalised my grandparents and outraged the morality of their generation. But their reaction to the affront was big-heartedness and generosity. I always thought of that act of acceptance as something quintessentially Indian. Not just among the elite, but within tradition as well.

Q/ A critic wrote: “The government has needlessly made a martyr for left-liberals out of an extremely privileged man who is basking in the publicity and the size of whose next book advance may have just tripled.” How would you respond to that?

A/ This is a coarse, stupid thing to say, let alone write. We always knew that there was an element of class warfare in the BJP’s programme, but even by their standards, this is excessive. Are we really at the point where we are saying an Indian writer, steeped in Indian concerns, ought not to be able to go home because he grew up in privilege? Moreover, there is not a single writer I know who has written more critically of the English-speaking classes in India than me. Every one of my books has dealt with the theme of the remove at which the English-speaking elite of India lived at from the rest of the country.

The “privilege,” by the way, had very little to do with money. Delhi in the 1980s was all genteel poverty and broken-down princes. Naveen Patnaik had a little black Fiat, my mother a green Suzuki. The palaces of mighty royals like the Jodhpurs and the Holkars were in a state of near total collapse. My mother had no money for years. Vasundhara Raje paid the rent, my aunt the school fees. But yes, if you mean I was privileged in that I never had to meet anyone as vulgar as your “critic”, it is true: I was supremely privileged.

Q/ You have a long fight ahead in which you said you “have no conviction that I will succeed. But I have no option but to try”. It gives the picture of someone who is wearied by it all. Are you?

A/ No. Everything is at stake—family, country, my material as a writer.... I will fight on. On the beaches, and in the shakhas, in courtrooms and newsrooms. And one day, they will be gone. And I will still be here. My grandmother may be dead. But I will honour the sense of belonging she instilled in me by coming home. It may be a melancholy homecoming, but there is nothing wrong with that.